My friend Kenneth Young, a University of Washington physicist now deceased, invited me in 1973 to join him for lunch at a U District cafe with the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Hans Bethe. We wound up talking about the disposal of radioactive waste. Bethe argued that there were plenty of plausible ways to dispose of radioactive waste; we just needed the political will to pick one. How about just storing them in steel tanks, I asked him. Surely that couldn’t be good. Sure it could, Bethe said, explaining scornfully that “only cheap tanks leak.” Weeks later, for the first time, news media reported that (cheap) underground metal tanks at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in arid central Washington had leaked some 115,000 gallons of radioactive waste into the surrounding ground.

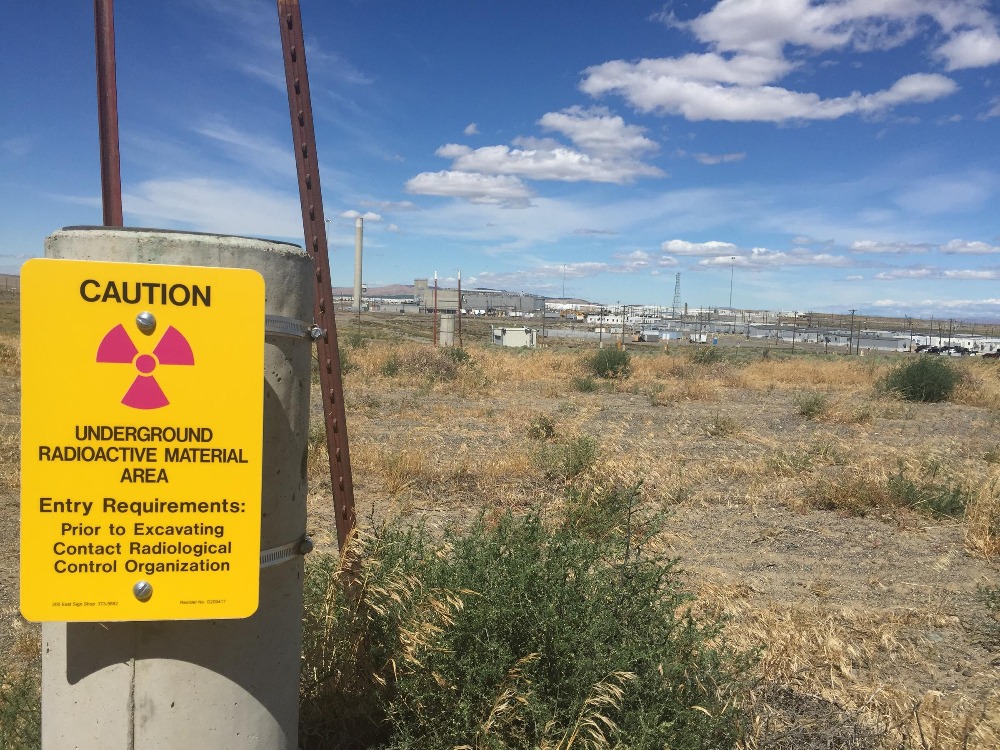

One hundred seventy-seven such tanks held something like 56 million gallons of radioactive and otherwise hazardous waste. The news was a bit unsettling.

Almost as unsettling these days is the news emanating from Hanford, where much of the nation’s high-level nuclear waste is stored. The facility recently laid off 50 workers out of a staff of 300, and more layoffs are ahead under orders from the Trump administration. Even scarier are some of the ideas for dealing with the nation’s nuclear waste as set forth in Project 2025, the conservative blueprint for government “reform.” To fully appreciate how scary, you need to know some history.

Hanford, beside the Columbia River and the Tri Cities, is probably the most significant historical site in the Pacific Northwest. It was the first plutonium factory in human history. It produced the plutonium that fueled the Trinity test, mankind’s first nuclear explosion, in the New Mexico desert near Los Alamos. Hanford produced the plutonium for the Manhattan Project, the World War II crash program to design and build nuclear bombs. Hanford made the plutonium that destroyed Nagasaki and ended World War II. And Hanford went on to supply the plutonium carried by America’s Strategic Air Command bombers during the scariest years of the Cold War.

These days, we hear a lot about Iran enriching uranium for nuclear weapons, which is indeed worth worrying about, but the big kids – the U.S., Russia, et. al. – have long built their weapons with Plutonium-239 from Hanford and elsewhere. Pu-239 has a half-life of roughly 24,000 years. It remains radioactive for roughly 10 times longer. In terms of human civilization, that may as well be forever.

The physicist Alvin Weinberg, who ran the Oak Ridge National Laboratory from 1955 to 1973, once told me that the commitment to store plutonium waste was unlike anything in human history he could think of, except Adolph Hitler’s instruction to his architect to create buildings that would last through the entire span of his “thousand-year Reich.” I quoted Weinberg to Jay Inslee when he was first running for governor. Inslee said, “In geological time, governments are short, radioactive decay is long.” Right.

The people who ran Hanford in the 1940s and 50s weren’t thinking long-term. The emphasis during World War II – and presumably, during much of the Cold War – was always on getting the plutonium out the door in a hurry, not on safeguarding for all eternity the waste products left behind.

The wonder is that it took 30 years before the tanks were first known to leak. It took another 16 years before the U.S. Department of Energy, which managed the site, joined the Environmental Protection Agency and the Washington Department of Ecology in signing an agreement that obligated the feds to clean it up.

We tend to think in terms of a perfect solution to the waste storage problem. But what is ever perfect? And do we have to come up with the solution right now? Not necessarily, or so I was told once by an official of the French national utility that runs that nation’s nuclear plants. Rather condescendingly, he explained that of course, as a young nation, the U.S. was impatient for a solution, but France, with a civilization that went back 1,000 years, could afford to be more patient.

His point might seem less ludicrous if you consider the solution that researchers at Hanford’s Pacific Northwest Laboratory (run by the Battelle Memorial Institute) came up with in the 1970s: loading radioactive waste into rockets and shooting it into the sun. A neat solution. But…

Around the same time, Edward Teller, “father of the hydrogen bomb” and the bad guy in the film “Oppenheimer,” came to Seattle to speak at the UW. At a small press conference, someone asked Teller about the shoot-it-into-the-sun idea. Teller was considered exceptionally pro-nuclear. One of his peers at the Livermore National Laboratory once said, “Edward loves bombs. He loves them. He thinks all the problems of the world can be solved by bombs. You name a problem, and he’ll design a bomb that will solve it.” Once, at a Congressional hearing, he was asked about the danger that radiation could cause mutations. Well, he said, some mutations are positive. Asked about shooting radioactive waste into the sun, Teller thought a moment, then said in his thick Hungarian accent, “Putting radioactive waste together with the rocket fuel . . . I don’t like it. I just don’t like it.”

Nobody else seemed to like it much, either. The waste has remained earthbound. And a lot of it has remained at Hanford.

At least some of it may do so for all eternity, or long enough that it may as well be. The initial drive to get plutonium out the door was certainly a rush job, but taking out the radioactive garbage has certainly been nothing of the kind. Sixteen years after that big tank leak was announced, Hanford cranked out its last plutonium, and the Department of Energy – which oversees the site – joined the Environmental Protection Agency and the state Department of Ecology in signing what’s known as the Tri-Party Agreement for a comprehensive cleanup. As deadlines have been missed, the agreement has been altered, but it’s still in force.

A core idea has been to “vitrify” the high-level waste, enmeshing it in borosilicate glass. To do this, contractors have been working on a giant vitrification plant – aka the “vit plant” – that is already many years behind schedule. People have vitrified waste before, but never at the scale Hanford requires. The job may never get done. Nikolas Peterson, executive director of the watchdog group Hanford Challenge, says he “absolutely” believes it will get done eventually. But he notes it has never been done before, and he says he’d probably “not bet on anything at Hanford being on schedule.”

And the vitrified waste itself may never leave. The vit plant was designed to produce glass logs that would be stored deep underground in the Nevada desert beneath Yucca Mountain, next to the Nevada Test Site where for years the federal government set off nuclear explosions. The government had chosen Yucca Mountain, but Nevadans didn’t like it. More importantly, one Nevadan didn’t like it: Democratic Senator Harry Reid, who became Senate Majority Leader when Obama was President. The Obama team certainly wasn’t going to go against Reid, and might not have pulled it off, anyway. (Besides, during his first Presidential campaign, Obama pandered to Nevadans by saying he’d shut down the Yucca project – just as Donald Trump later pandered to them by saying he’d get rid of taxes on tips.) Yucca was scrapped. There was no Plan B. A “Blue Ribbon Commission” said forthrightly that the nation should put radioactive waste someplace where the people wanted it. Lots of luck.

But is the idea of storing radioactive waste at Yucca Mountain really off the table? Not according to Project 2025. “According to both the scientific community and global experience, deep geologic storage is critical to any plan for the proper disposal of more than 75 years of defense waste and 80,000 tons of commercial spent nuclear fuel,” it says, and argues that “Yucca Mountain remains a viable option for waste management.” Asked if Yucca Mountain was still a possibility, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright did not deny it.

An aside: Hanford may in one sense be an albatross around the state’s neck, but has brought benefits in other ways. It has supported thousands of jobs in central Washington for more than three-quarters of a century. (Biden’s last budget calls for spending $3 billion there.) Its fences have kept development away from Washington’s largest swath of shrub-steppe habitat. Its high-security mission kept dam builders away from the river at its doorstep, so that Hanford Reach, the stretch of the river beside the nuclear site, has remained the Columbia’s only free-flowing stretch above Bonneville dam. What will the Trump administration do at Hanford? No one knows. But Project 2025 offers hints, noting that some states see waste management “as a jobs program and have little interest in accelerating the cleanup.” Looking at you, Washington. But really, does anyone think the Hanford delays have been caused by self-interested foot dragging, rather than difficult technical problems and maybe incompetence?

Citing a need to expedite the process, Project 2025 notes that Hanford “is a particular challenge,” in that the Tri-Party Agreement “has hampered attempts to accelerate and innovate the cleanup.” Does that mean the feds should try to weasel out of the agreement?

The authors certainly suggest that a way to deal with high-level waste would be to simply reclassify it. “A central challenge at Hanford is the classification of radioactive waste. High-Level Waste (HLW) and Low-Level Waste (LLW) classifications drive the remediation and disposal process. Under President Trump [in his first term], significant changes in waste classification from HLW to LLW enabled significant progress on remediation. Implementation needs to continue across the complex, particularly at Hanford,” where newly reclassified LLW could “be grouted rather than vitrified.”

Grout is, of course, the kind of slurry that fills in the cracks between tiles in your shower stall or kitchen backsplash. Grouting waste reclassified as “low level” would be a lot quicker and cheaper way to dispose of it. The federal government started this during Trump’s first administration.

The Project 2025 authors recommend accelerating the cleanup, meaning “a 10-year program to complete all sites by 2035 (except Hanford with a target date of 2060) should be considered.”

In the short term, this would not mean spending less. Rather, it “will require increased funding . . . during those accelerated periods.” But don’t worry, this wouldn’t mean new taxes. “To the extent that funding from the [Infrastructure and Jobs Act] and [Inflation Reduction Act] cannot be repealed, requests to divert those funds to cleanup obligations should be considered.” Basically, don’t spend the money as it was intended – but, of course, let Trump take credit for the jobs those laws will create.

Peterson of Hanford Challenge says the recommendation for more funding and an accelerated pace are pleasant surprises. But he says the recommendation to reclassify more high-level waste is not. In fact, he says, a government decision to just reclassify and grout more waste is his “greatest fear.”

He says some groups that support Hanford Challenge are all for it, believing it will get waste out of Hanford faster. He’s not so sure. A lot of grouted waste could just pile up at Hanford. He’s pleased that the Tri-Party Agreement calls for just-in-time shipment of the grouted waste; that is, don’t grout more waste until you have a place to store the grouted waste you already have.

Peterson also likes that the agreement talks about not using the Department of Energy’s revised definition of what constitutes low-level waste. But he says that language is not iron-clad, and in any event, if Congress passed new legislation about reclassifying waste, there would be “no way to really stop it.”

Note that Project 2025’s conservative authors pick 2060 as the optimistic, pie-in-the-sky completion date at Hanford. That’s eight administrations from now. What are the chances the cleanup will really be done by then?

If it isn’t, we’ll have to live longer with the fact that, as Peterson says, “if there’s a bad day for Hanford, it’s a bad day for a three-state area.”

We haven’t had a really bad day at Hanford yet. Good for us. And if we hit anything close to that 2060 cleanup target? Somewhere or other, vitrified or not, that plutonium waste will still be with us. But not forever, really. It will reach its half-life in only about 240 centuries.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Somewhere or other, vitrified or not, that plutonium waste will still be with us. But not forever, really. It will reach its half-life in only about 240 centuries.

Here’s your headline. Use it often!

“Plutonium waste will reach its half-life in about 240 centuries.”