Thomas Kohnstamm will speak about Supersonic and sign copies at:

- March 12, at Phinney Books, in conversation with Tom Nissley of Phinney Books

- March 28, at Third Place Books in Ravenna, in conversation with Moira Macdonald of The Seattle Times

- April 24, at Third Place Books in Seward Park, in conversation with Cynthia Brothers of Vanishing Seattle

- April 30, at Elliott Bay Book Company, in conversation with Jonathan Evison

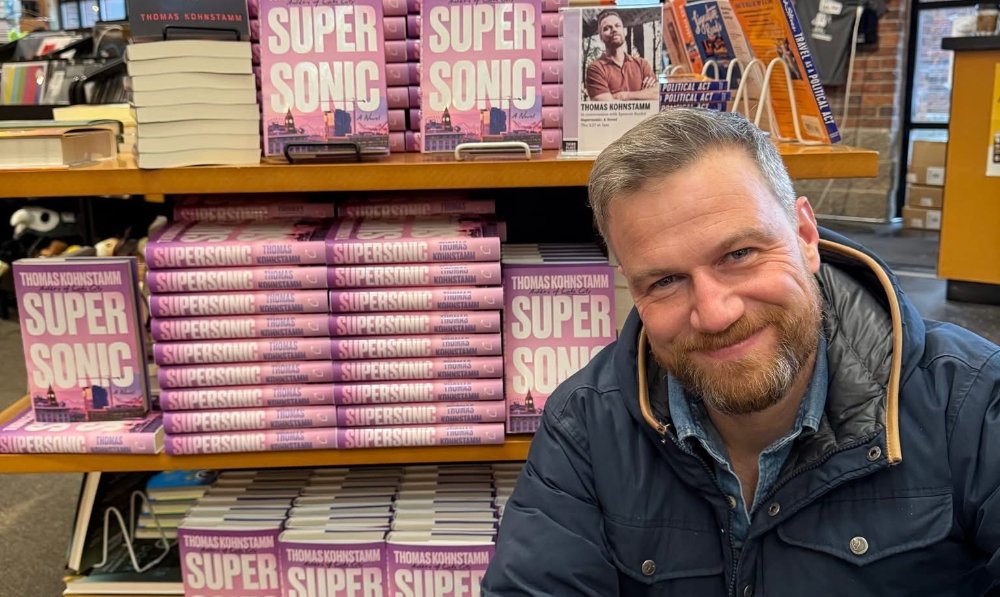

Thomas Kohnstamm will own it: He set out to write nothing less than The Great Seattle Novel. And in Supersonic (released Feb. 25 by Counterpoint Press), the 49-year-old Seattle native might have done just that, if only in its unprecedented sweep and scope.

The novel is a “creation myth” spanning nearly 120 years of the city’s boom-and-bust cycles. And its title is the novel’s central metaphor for boom and bust, Seattle style., and the reason about half of Supersonic is set in 1971—possible the biggest boom-to-bust year in Seattle’s history.

Development work of the supersonic jet—essentially, the American equivalent of the British Concorde—swelled Boeing’s ranks, and Seattle’s fortunes, throughout the 1960s, making it “the biggest company town in America,” Kohnstamm says. And when the federal government abruptly canceled the project’s funding in 1971, more than 60,000 living-wage Boeing jobs disappeared almost overnight. (Remember the sourly wry “Will the last person leaving Seattle — turn out the lights” billboard near Sea-Tac?)

But in the bigger sweep of Seattle-area history, that bust laid the foundation for the next boom, as Kohnstamm sees it.

“It’s about optimistic if not utopian thinking, reaching for the stars, then falling on your face, then dusting yourself off, and getting not what you want but what you need,” Kohnstamm said. “The engineering culture that was created around that arguably created the groundwork for the rise of the tech industry that really came to fruition with Microsoft’s IPO in the 1980s, still around a single company at that point.”

He set about half the story in 2014 because, once Amazon started turning a profit, “Seattle was really booming, with tons of building, and that was the moment of maturation for our tech industry.” And it was the launch of the legal recreational-cannabis industry in Washington state, which is the basis of one of Supersonic’s plotlines, which drafts on that boom.

Supersonic’s point-of-view characters include a Duwamish tribal member; three generations of Japanese-American women; a machinist on the Supersonic project; and a middle-aged ski bum turned would-be cannabis entrepreneur, among others. What thematically links each of them and their quests is their attempt to hold on to something they prize from the past—while being slow to recognize that the future is pulling the present out from under their feet. That Seattle is growing—and changing, obliterating, reinventing itself—that fast.

What each character is slowly and painfully being forced to accept, Kohnstamm says, is that Seattle is no longer a “backwater,” a place for people to come in search of escape from what they perceive as more stultifying parts of America. “The whole world is in Seattle now, a much more connected part of the wider world,” and thus shackled to the ever-increasing speed of that ever-intensifying connectivity. Consequently, those not fully connected to the forces powering that fast engine are at perpetual risk of being left behind.

As a result, Kohnstamm said, “I don’t think we have a really good sense of who we are. The present changes so fast that the past gets forgotten.”

It’s the kind of widescreen view that few novels set in Seattle have succeeded in getting their arms around. (Possibly the closest analog is Jim Lynch’s Truth Like the Sun, which splits its story between the run-up to the 1962 World’s Fair that spawned the Space Needle and Seattle Center, and the Seattle of 2001.)

Kohnstamm sets his sights wider: “I wanted to write a novel about the rise of a city, that takes the full measure of a place.”

That’s literally true, in a sense. While Supersonic’s setting is unmistakably Seattle, the name “Seattle” is nowhere to be found in the novel’s 385 pages. Nor is Amazon or Microsoft; those companies are referred to interchangeably as “Mothership.” Kohnstamm didn’t want his creation myth to get bogged down by obeisance to strict historical fact. He wanted Seattle to be uniquely itself, but in the service of larger themes. “I wanted to get to the emotional core of a place,” he says, “without being hung up on ‘was that 1852 or 1853, or did that happen in spring or fall of 1971?’”

So, who is Thomas Kohnstamm, and why does he think he can tell this story?

He’s a 1994 Roosevelt High graduate, who owns and lives in the same Lake City-adjacent home in which he was raised. He went to the East Coast for college and earned a master’s degree from Stanford in Latin American studies. His first career was as a travel writer, and his global adventures as a “parachute artist” for Lonely Planet set the table for his first book, the gonzo memoir Do Travel Writers Go to Hell? (2008).

Once he married and started a family, Kohnstamm kept his hand in freelance journalism while developing a home-based video and animation studio, providing multimedia storytelling for some of the same big-tech behemoths that he (gently) satirizes in his fiction. His first novel was the well-received Lake City (2019); a Seattle Times review called it “a caustic satire on class privilege and deprivation.”

(Full disclosure: I was hired by Kohnstamm, in 2017, to edit an early draft of Lake City.)

Kohnstamm’s second novel, set partly in Seattle, was shelved because his literary agent wanted him to go bigger and wider. His next effort started as a lightly comedic story about PTA parents battling at a Seattle elementary school auction over what the future of the school should emphasize. (That storyline wound up being just one of the several in Supersonic.)

Once again pushed to go bigger and wider, Kohnstamm turned to his closest literary friend, Bainbridge Island author Jonathan Evison, who had helped him with Lake City as well. Kohnstamm is an admirer of Evison’s second novel, 2011’s West of Here, which encompasses more than 120 years and more than a dozen point-of-view characters in its creation-myth tale set on the Olympic Peninsula. Kohnstamm wanted to model his story on that sort of epic structure.

Over many beers and many sessions in Evison’s garage writing space, Kohnstamm took to heart his friend’ and mentor’s advice: Stop “pre-planning” and just let the storylines flow organically from his subconscious mind, from situation and character. He followed that advice so well that he wound up cutting more than 30,000 words from his first draft. Evison, at Supersonic’s Feb. 27 launch event at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park, jokingly referred to Kohnstamm as “de Maupassant to my Flaubert.”

In this age of sensitivity toward cultural appropriation and writing characters outside one’s lived experience (remember the American Dirt controversy of 2020?), Kohnstamm understands that some may question how a white guy can credibly depict point-of-view characters from other cultures.

His simple response: Keep your good intentions in front of you —which in his case began with a desire to not tell Seattle history through a white-history lens — and back them up with conversations and research. And, he added, “bring it back to the humanity.”

He talked to a retired Boeing employee; to inform his Duwamish character, he talked with Duwamish Tribal Services, and they also referred him to Seattle author and historian David Buerge, who edited historical details in a number of Supersonic’s chapters. And to add depth and verisimilitude for his storylines about the three generations of Hasegawa women that give Supersonic its gravitational center, Kohnstamm spoke to, among others, a neighbor—a niece of Claire Suguro, who was believed to be the first Japanese-American teacher in Seattle Public Schools (as Masako Hasegawa is in the novel).

The close-third-person chapters of each of the Hasegawa women are the most emotionally resonant parts of Supersonic: Masako, the music teacher who, in 1971, is determined to freeze her daughter Ruth in her culture’s past as she defines it; Ruth, equally determined to spread her wings and fly during the fledgling feminism of the time; and Sami, the no-less-determined granddaughter who fights, in 2014, to preserve her grandmother’s arts-first legacy by fending off the STEM tide of the time and placing the family name on the elementary school where Masako taught — even as it’s targeted for closure.

Kohnstamm’s guiding principle was, simply, “We’re all just people, fundamentally. We all have the same emotions, the same desire, the same quests for status.” (He added that “I worked closely with people with lived experience, and they read my final drafts.”)

He believes that his perspective as a Seattleite who’s lived a large chunk of his life outside of the city—much of it spent writing about other places for a living— gives him a stronger vantage point from which to write about Seattle.

“I’m willing to own some over-arching takes on things,” he said. “I’m willing to make some broader descriptions, draw some points about the culture, right or wrong. I’m willing to own them because I have as much depth on this subject as anyone.”

And to many of his Seattle literary peers, Kohnstamm’s execution has equaled his ambition.

Evison is thrilled with his protégé’s finished work: “I wish I could write The Great Seattle Novel, but I’ve always felt Thomas was the right guy for the job. He’s a walking Seattle encyclopedia.”

Fred Moody, longtime Seattle journalist and author of Seattle and the Demons of Ambition, is another admirer. “His characters are really well chosen, representing real Seattle archetypes, and all of them are sensitively and thoroughly drawn. …I am particularly impressed with the care and careful research that went into depicting the stories, histories and viewpoints of Seattle’s ethnic minorities, who have long been overlooked in various Seattle mythologies.

“I regard this novel as one of the best—possibly the best—capturers of Seattle’s … Seattle-ness.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.