Production design is usually relegated to the end of most opera reviews, but the team behind Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” now playing at Seattle Opera deserves mention at the outset.

Komische Oper Berlin Artistic Director Barrie Kosky engaged the English collaborative “1927” (Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt) to help him create an interactive scenic concept for Mozart’s final, fantastic singspiel. A co-production of the Komische Oper Berlin-Los Angeles Opera-Minnesota Opera, the result must be seen to be believed.

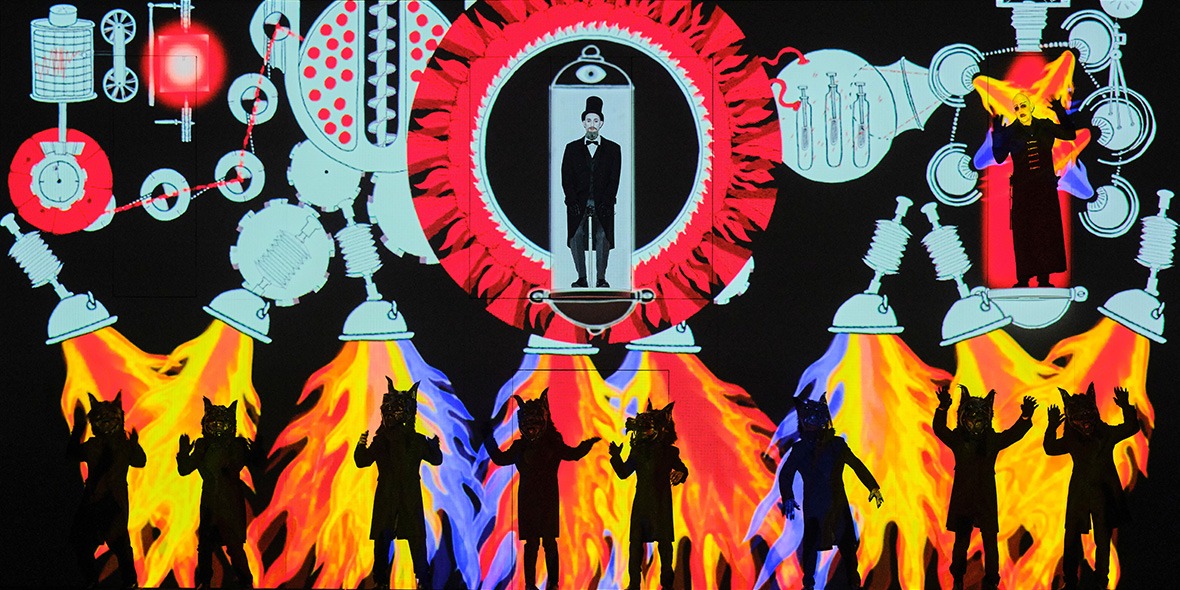

Barritt’s images, projected onto an advent-calendar-like wall, recalled to me Terry Gilliam’s cut-out sequences for Monty Python’s Flying Circus at times, or German expressionist cinema at others, all overlaid with a healthy dose of Edward Gorey.

What further distinguished these projections were musically synchronized animations, images that sprang into being on any given vocal cue, capering about to the beat of the score. This was achieved by carefully placing singers in front of the projection wall or having them appear from within the wall above at discrete locations. By combining spotlighting with projections, a sequence of hilarious effects was achieved.

Maestro Christine Brandes led a brisk account of the brilliant overture, pointing up accents and highlighting its multiple layers of counterpoint. In the problematic first scene, the animated sequence yielded immediate dividends. Prince Tamino (tenor Victor Ryan Robertson) and the three servants of the Queen (sopranos Ariana Wehr and Ibidunni Ojikutu and mezzo-soprano Laurel Semerdjian) were variously menaced by and triumphed over by a great serpent. Here a hopelessly unstageable sequence was finally and entertainingly realized.

Cue Tamino, running full tilt at the audience, his sprinting legs an animation. Cue the meat-grinder teeth of a great flying beast overwhelming the stage. Cue the bone-filled lair of the Black Beast of Aargh (Python fans take note.) Cue the three ladies, each sprinkling little flying hearts over the fainted prince below. These visual gags came fast and furious and might have threatened to overwhelm the show were they not so effectively integrated with the music.

I imagine this required constant synchronization, namely between the conductor adjusting tempi to fit with animation sequences and the projection team tracking every bar of the score. The effects, in adding a new layer of information to the opera, ultimately filled in many of those fantasy elements only dimly realized in a traditional production.

In keeping with the twenties aesthetic, silent-film-style intertitles took the place of spoken dialogue. Thus the question of whether to present speech in German or English was sidestepped. In its place came admirably-rendered little links between scenes. These were accompanied by minor-key sequences from Mozart’s solo piano oeuvre. Fortepianist Jay Rozendaal performed these with a melodramatic wink and doubled on the celeste when Papageno’s magic bells were invoked.

This inter-title innovation also allowed the singers to relax a bit. Spoken dialogue in “The Magic Flute” has always seemed to me overwrought, especially when it comes to Papageno. This was the role the librettist Schikaneder himself played, and it is packed with shtick that rarely comes off as funny. Costumed as they were in outlandish period garments and made up with high-contrast mascara and lipstick reminiscent of the Kit-Kat Club, in this production all the singers had to do during these sequences was mug into the spotlight and the laughs came.

Tenor Victor Robertson, sporting evening wear, produced a sound reminiscent of the great James King. Robertson hasn’t the vocal heft of the late heldentenor, but he navigated “Dies bildnes” beautifully and hit his marks perfectly and on time, seamlessly integrating the projected animations into his movement. The magic flute (flutist Jeffrey Barker) he is given appears as a fairy that flits about when the flute plays. This was a bit confusing, for there was no visual reference to it being played by Tamino. Likewise, the burlesque dancers deployed at the sound of Papageno’s bells seemed detached from his intention.

The three ladies brought to mind the Triplets of Belleville, their impetuous vocalizing laughably countered by a matronly fur-collared stodginess. They were somewhat loath to attend the evil Queen of the Night (soprano Sharleen Joynt,) and for good reason: she hovered menacingly over her minions, a gigantic spider given to fits of vengeful fioratura. Apart from some fuzzy passagework in her first aria “O zittre nicht,” Joynt managed the pinpoint high-Ds and Fs well, especially later in “Die hölle rache.”

Baritone Rodion Pogossov’s Papageno, in yellow pin-stripes and porkpie hat, gave a stone-faced impression of Buster Keaton, and his bird-catcher-who-catches-anything-but-birds was a welcome take on a role difficult to characterize. The animations that appeared during his lonely musings were of the dance-hall burlesque variety. The role suited Pogossov vocally, and for all the extraneous visual information that swirled about him, including a pet cat, he managed to endear rather than irritate. The visuals during his duet with Papagena (soprano Tess Altiveros,) a houseful of the ugliest little children imaginable, brought down the house.

Monostatos (tenor Rodell Rosel) appears in the original score as a rapacious Moor. A common theatrical trope in Mozart’s time, it’s untenable today, and the hideous character was reimagined as Nosferatu. Rosel made some admirably ugly sounds to match his ghoulish appearance.

Soprano Camille Ortiz’s voice, while perhaps not the ideal silken sound one hopes for in Pamina – was convincing in another difficult role. Wavering between obedience to her tyrannical mother, obeisance to the paternalistic Sarastro, and dedication to the unresponsive Tamino, she finds herself in a man’s world, and emerges victorious. Her flapper look recalled Louise Brooks, and Ortiz mesmerized with a floated high G at end of “Ah, ich fuhls.”

Sarastro (bass In Sum Sing) was suitably square. Any performance of the role I’ve witnessed, and this was no exception, seems to demand the utmost concentration from the singer. This tends to make the listener nervous, as if the priest might be in danger of missing his low notes. In Sum Sing made his, although not without effort. He was helped by the excellent men’s chorus, stacked up on either side of the stage like top-hatted long beards sitting for a daguerreotype in the balcony of some musty old Masonic Lodge. Appearing front and center for “O Isis und Osiris,” they were helped by the projection wall, which bounced their sound into the house thrillingly. The women joined for a rousing curtain closer.

The Three Genies, who have much more music than one remembers, were beautifully sung by sopranos Sanne Christine Smith, Grace Elaine Franck-Smith and Anthony E. Kim. The treble trio functions as a single character in scenes with Pamina and Papageno, with music so carefully wrought that it falls flat if performed by mature voices.

My wife, for all her bellyaching about the relentless misogyny of the libretto (“Women need men to guide them…all they do is talk,” which drew hisses from the audience,) kept marveling at how clear the story came through, nothing like the muddle she remembered from past productions. Despite the swirl of fantastic imagery, this production of “The Magic Flute” kept its singers mostly stationary, allowing them to focus on musical values before stagecraft.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

We saw this last night — the imagery was interesting but it really overwhelmed the talent of a live performance. Were those actors singing on the stage or was it a recording? How on earth does one peel their eyes away from the animation to read the superscript? I have no clue what the plot was. Perhaps an interesting/refreshing take for opera veterans but I didn’t really get the joke, or anything about it.

I saw the performance of last Wednesday, the 26th, with a slightly different cast—not that the cast makes much difference, since all the singers are overshadowed by the projected animation in this staging. Their function is that of mere puppets as far as the stage action is concerned. The animation is undeniably clever and inventive, but it completely undercuts the drama. Until now, I never thought it possible for a competently sung, played, and conducted performance of Mozart’s crowning operatic achievement to be completely devoid of emotional impact. But the production team managed that very unadmirable feat. Eventually, I managed to restore some of my feeling for this opera by CLOSING MY EYES to listen. How anyone but a Philistine or an ignoramus can applaud this production is inexplicable to me.