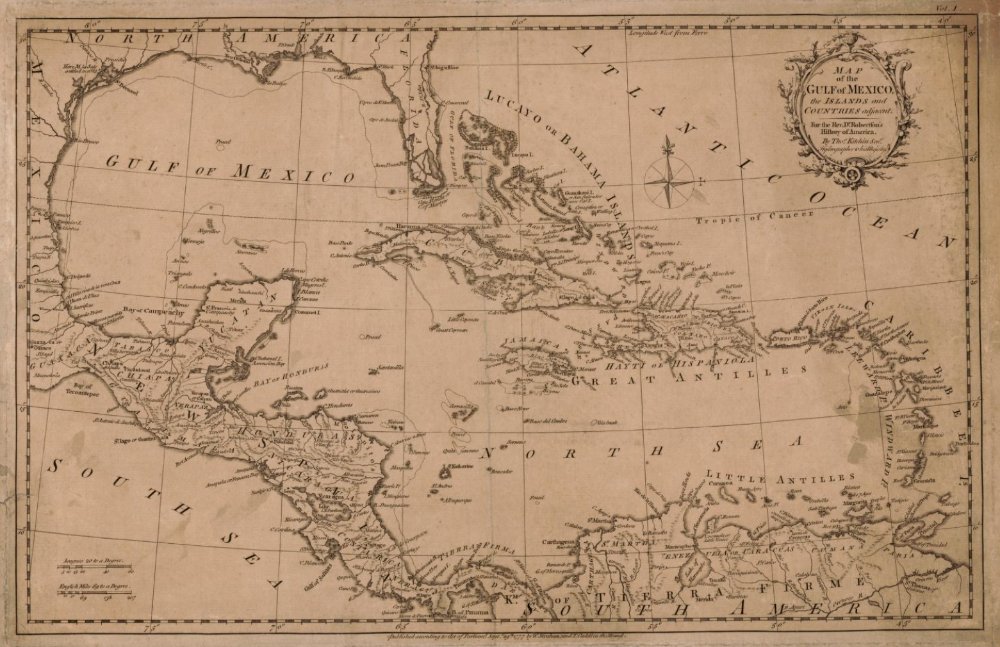

Beginning his second term in office, President Donald Trump quickly issued an executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico as “the Gulf of America.” He is not alone in his historical ignorance of the Americas. In my formal education, I cannot recall a single class in which the large number of Spanish place names in Washington were explored.

As a teacher at the St. Catherine School in north Seattle, I sought to remedy that ignorance. In place of a standard history text, eighth graders read and digested primary sources describing beginnings and turning points. One was the Diario of Christopher Columbus, an abstract of his log describing the first voyage across the Atlantic, written by the Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas in the early 1600s.

After 34 days sailing beyond sight of land, Columbus’s terrified crews threatened mutiny. But by the light of a full moon, Pinta’s lookout, Rodrigo de Triana, spied an island’s white cliffs. It was October 12, 1492, and that island, Guanahani, “Iguana Island,” is in the Bahamas. Columbus called it San Salvador, “Holy Salvation,” because its discovery saved the voyage.

I never read that account in any class, and I majored in history. But seeking writings that young students could never forget, I used others like it. The History Of The Indies of New Spain was written between 1586-89 by a Dominican, Diego Duran, whose family

moved to the New World in the mid-1500s. He remembered losing his baby teeth in the town of Texcoco on the great lake of that name. He learned Nahua, the language of the people we call Aztecs, but who called themselves Mexica.

I had a large Mexican flag hanging on the back of my classroom and told students to learn the meaning of its central symbols: an eagle, wings spread, standing on a prickly pear cactus with a serpent in its mouth. This required reading the first five short chapters of Duran’s history based on information provided to him by Nahua elders and ancient texts written in the Nahua. All but four of thousands of these texts, painted in brilliant glyphs, were burned by clerics who believed them idolatrous — a massive cultural loss.

Duran’s account begins around 1054, a time marked by the explosion of the Crab Nebula. Following prophecy, the Mexica left seven northern caves in Aztlan (possibly in the American Southwest), commanded by their god, Huitzilopochtli (Hummingbird on the left), to go south in search of the holy sign. After adventures and misadventures, they arrived at Lake Texcoco, whose shores were punctuated by great cities.

Residents regarded the Mexica as poor immigrants, Chichimeca (“Sons of Dogs”), and allowed them to settle only on stony wastes where they foraged lizards, snakes, and insects. Quickly tiring of this, they stopped honoring Huitzilopochtli, even throwing their waste into his portable altar carried by his priests on the long journey.

To restore their status, the priests came up with a plan. They asked a local king to let his daughter honor their god in ceremonial marriage. The king agreed, but when invited to witness it, saw that the priests had skinned her, and one wore her skin. Enraged, the king called his people to slaughter the Mexica. They attacked, burned huts, and drove Mexica survivors into the lake where they trembled among the reeds. A light piercing the mist and smoke illumined a great eagle, warming its spread wings atop a prickly pear, holding a serpent in its beak. This would be their new home.

Over time they dug and piled lake mud into staked enclosures, creating chinampas, (“floating gardens”) to raise crops and flowers. As the gardens grew, around 1325 they created a city, Tenochtitlan, named after Tenoch, their leader at the time. It became the capital of a great empire that ruled the lake valley and surrounding lands.

The Mexica raised a great pyramid, the Templo Mayor, in their city’s center topped by shrines to Tlaloc, god of vegetation, and, on the left or south side, to Huitzilopochti. On these, young captives were sacrificed, reducing the ability of vassal states to wage war. Duran wrote these stories down decades after the Spanish under Hernan Cortes captured and destroyed Tenochtitlan after a long and terrible siege.

Students also read parts of True History of the Conquest of New Spain, by Bernal Diaz del Castillo, a conquistador who accompanied Cortes on his march from the Gulf to Tenochtitlan in 1521. He described the epic meeting on the great causeway across the lake to the city where Cortes met the Emperor Moctezuma II. From his memories Diaz wrote how Spaniards had difficulty finding words to describe the beauties of Tenochtitlan, divided by canals like Venice, before it was leveled by Cortes.

From the stones of Templo Major, Cortes had built baroque Metropolitan Catherdral, oldest and largest in Latin America. The city’s huge market became the vast Zocalo, the modern city square, and Moctezuma’s palace was demolished to build Cortes’s house. These accounts are thrilling and terrible.

On the evening of October 12, in the candle-lit stern cabin of his flagship Santa Maria, Columbus penned a letter to his patrons, the Catholic monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, describing the events of that extraordinary day. The generous people he met on Guanahani swam and paddled out to his three ships, asking if he and his crew came from the heavens. Bemused crews waved, and the people — “Indios” Columbus named them, believing he had reached India — called to their families on shore, “Come! Bring food and water to the men from the heavens!”

In his letter, Columbus wrote that they “would make excellent servants.” He repeated a terrible judgement made a half century before when Pope Nicholas V allowed the king of Portugal to enslave and sell all non-Christians in north Africa to help pay for the Crusade he was waging on the Pope’s behalf against Muslims. The right to profit from enslaving people in perpetuity was also awarded Spaniards in the New World after Columbus’s voyages.

That catastrophic permission is at the heart of the “Doctrine of Discovery,” arguing that Native Americans did not own the land but only occupied it. Quoted by Supreme Court Justice John Marshall, the doctrine has been used to justify the United States’ claim to native land and for concentrating Indians in encampments we call reservations, in order to acquire a continent for settlement.

The Gulf of Mexico recalls the rise, fall, and fate of the Mexica. The narrative is prologue to the Euro-American experience in the New World: the assault by Spain, Portugal, France, The Netherlands, Russia, Great Britain and, ultimately, the United States, the “Colossus of the North,” upon the land and its people. Changing this to the “Gulf of America” is a sop Trump throws to his befuddled supporters.

We should not sentimentalize the Aztecs. They practiced human sacrifice on an industrial scale, as did Catholic Spain during the Inquisition when it burned thousands of heretics alive in public celebrations — auto-da-feys (“a raising of the spirit, an act of faith”). Students read first-hand accounts by those who witnessed these gruesome events.

Students also studied the Roman Constitution, Justinian’s Code, the bases of continental law, English Common law, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the English Declaration of Right in 1689 that preceded and influenced our Revolution, our Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. I longed to have students explore the role of Islam in early southern slave rebellions, but we ran out of time.

The present occupant of the White House has obviously never read history or cares to. He and his supporters prefer a puerile chauvinism to histories that more properly define us.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks David for sharing this vivid history in response to Trump’s aggressive ignorance and arrogance. Heartening as the. Musk/ Trump regime works to erase our history as it demolishes our sacred institutions. Your words and scholarship are critical at this fraught time.

So how many names does Deutschland have? Even cities in Germany are called differently in the English language. Why does the left always have to insult anyone who doesn’t follow their direct path. Stop the Trump derangement syndrome already, it is so childish!

Stop defending Nazis, dude. It’s a particularly bad look when you have a Germanic name.

PS – they changed the name of the Sudetenland after enough Nazis were killed. The Gulf of Mexico is still the G.O.M, delusions of a lying thieving rapist notwithstanding.

Totally irrelevant. The Rio Grande River is named Rio Bravo in Mexico, and was previously named Rio de las Palmas. Governments can call any geographic location any name they want. Where’s your outrage about the US naming the country that calls itself Deutschland, Germany?

Are you an advocate of BCE & CE? What parameters would allow for changing historical landmarks and references.

What lucky students to have you as a teacher. Thank you for our lesson today.

Thank you for the historical perspective. However, throughout history, many governments worldwide have renamed cities, streets, towns, and more. For instance, Germany was known as Prussia in the 17th century, and Turkey has recently rebranded as the Republic of Türkiye. Therefore, your argument appears irrelevant, as many others have also renamed various places throughout history. While I understand you may not support the president, which is your right, the historical context does not directly relate to the name change. That ancient civilization has long since disappeared, and even Mexicans have renamed and altered many of those places.

David Buerge, not many outside of your circle really care. Trump, I’m sure knows history and is decently educated. He feels he is doing what he was elected to do. He has built many landmarks across the US and the world. This is not about him but his desire to put the USA on top again.

Sorry, but D Trump is not too sharp on history. Today, for example, he blamed Ukraine for starting the war that has devastated that country for three years. However, it was Russia that launched a bloody, unprovoked invasion to crush a democratic sovereign nation. And the Musk-Trump regime is now barring Ukraine from peace negotiations as it supports antidemocratic, NeoNazi forces in Europe to the delight of the autocratic leader of the aggressor nation.

“E” , ” I’m not surprised you didn’t attach your real name to the comment put the “USA on top again”, what are your examples of the USA failing to be “on top”? If you mean, Trump and his ilk who can’t wait to bully and harass a sovereign nation, such as Ukraine, then say so.

Why do we still call the state “New Mexico” and not “New America”?

You neglected to name at least four names for this body of water prior to it being called The Gulf of Mexico. I find that very strange for someone who is a history professor. What makes one name preferable to another? Does anglicizing “Golfo de Mexico” make any more sense than renaming it something else? Does calling said body of water Golfo de Nueva España instead of Chactemal cause the same outrage as calling in Gulf of America? How about Mar del Norte, or Golphe du Mezique, why aren’t these names held in the same esteem as Gulf of Mexico?

Thank you David for providing this historical perspective. It’s interesting how different groups of people and nations name things. Sometimes it’s the inspiration of the moment and others it’s practical for what the place means for food and shelter. Thanks for the reminders.

Meanwhile Trump is simply asserting his dominance. He’s establishing a dictatorship. Dictators get to name things whatever they want. It’s a lot simpler than going through the US Board of Geographic Names…though he’s doing that too. Soon, that board will renaming all sorts of things to keep up the pretense of a “white christian nation” . Their meetings should be entertaining if not so sad.

Okay, so you don’t like Trump, but your article fails to provide any evidence that he is historically ignorant. I don’t consider Washingtonians historically ignorant just because after more than a hundred years they have failed to rename their state which was named after a slave-owning, 18th century Virginian. The Mayan’s called the gulf “nahá,” meaning “great water,” and the Aztecs called it “Chalchiuhtlicueyecatl,” a reference to the Aztec god of water and fertility. Even after the Spanish arrived in the 16th century the gulf was sometimes referred to as the “Gulf of Florida,” the “Gulf of Cortés,” or the “Sea of the North.” Other prior names for the gulf include the “Gulf of St. Michael,” the “Gulf of Yucatán,” the “Yucatán Sea,” the “Great Antillean Gulf,” the “Cathayan Sea,” and the “Gulf of New Spain.” Today Google maps calls it “Gulf of Mexico (Gulf of America).”

Was it OK for Biden to rensme places in the US to match his and Obama’s ideology. Changing history to match their WOKE agenda? Ignoring the very valid reasons these names were chosen in the first place? How about the defacing/destruction/removal of statues of historical figures. Like that of the first black justice on the US Supreme Court. They want to institute “democracy “ which our founders hated distrusted based on history. They want to remove a protection of small states from the oppression of the high population states controlling the presidential elections FOREVER. They want to revise the Senate for the same reason. It gives the small rural states too much power to stymy the leftist totalitarian high population states. But this guy wants us to worry about irrelevant history some of which I am not sure is even accurate.

Gee, Seattle … who would’ve guessed an article calling the President ignorant came from there. I noticed the names Gulf of Florida, Sea of the North, Gulf of Cortez, Gulf of St. Michael, Gulf of Yucatán, Great Antillean Gulf, Gulf of New Spain, etc. etc. … weren’t mentioned. Perhaps the third grade teacher didn’t know this.

Richard, you’re obviously picking and choosing examples. Maybe you didn’t know:

Seattle and Washington state seem to be stuck with “Rainier” for the state’s highest peak, instead of the native “Tahoma” .Capt. Rainier never visited the state. Pity, too, that Trump ignored Alaskans’ wishes to keep “Denali” a native name meaning “tall one” for the mountain. He just couldn’t wait to rechristen “McKinley”.

Does Mexico even have boats . Maybe we should fence it or just tell Mexico if they don’t like it then sell there good somewhere else and buy from some one else too