[Editor’s Note: Eric wrote 59 stories for Post Alley. You can read them here.]

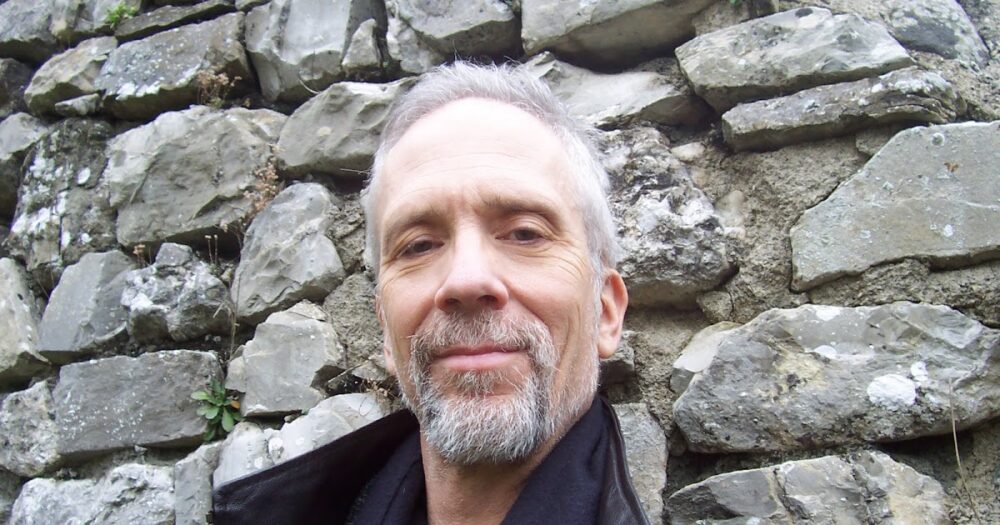

Seattle author, reporter and editor Eric Scigliano, 71, who died last week in a diving accident in the Galapagos Islands, won’t be forgotten by his enormous network of friends in the local news community, who’ve recently gathered online and in person to tell Eric stories for hours.

Nobody lived a bigger life, or wrote more ebulliently and prolifically, for all manner of media: the Timeses of Seattle, New York, and L.A., the Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, ARTweek, Harper’s when it was the hot book, The Atlantic now that it’s the hot book, even the Zimbabwean. He was forever on a global adventure, deeply rooted in Seattle. He was like the electron in Bohr’s model of the atom: not to be found on a predictable orbit, but rather at any moment somewhere in the universe on a cloud of probability, with Seattle as his orbital shell.

If he wasn’t exploring the old tunnels left by Vietcong decades after the war, he was swimming with a giant octopus in Seattle’s aquarium, or spelunking the incredibly fancy restroom beneath the Pioneer Square Pergola, built for the 1908 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition for over $760,000 in modern dollars. Eric loved that bathroom.

I met him at Seattle Weekly (then known rather imperiously as “the Weekly”) circa 1980, shortly after he’d moved from Santa Fe, where he’d dropped out of St. John’s College to become a cartoonist, then a writer for the Santa Fe Reporter. (He was always a good cartoonist – his excellent sketch commemorating the birth of his daughter Kate, speculating on the dazzling things she’d grow up to do, brings tears to my eyes).

He’d also studied at America’s most studious junior college, Deep Springs, where students worked 20 hours a week on a ranch, then studied the classics. He came off like a cross between Bullwinkle, Anthony Bourdain, and Pliny the Elder and Younger put together. For an intellectual luftmensch, he was remarkably resourceful: when others sat and complained about a deafening car alarm on the street outside the Weekly office, Eric grabbed a screwdriver and MacGyvered it into silence.

He told me his car broke down on the way to Seattle, so he sold it to a guy on the road for chump change, bought a car with non-working headlights, and figured he could get through California without getting busted since Proposition 13 had torpedoed funding for cops on the highway. He arrived unarrested.

The only time I saw him scared was when we were both working one Sunday in the otherwise deserted Weekly office, and his dog Gazebo pooped hugely on the pile of papers around our editor David Brewster’s desk. I told Eric, who somewhat resembled Gazebo, and his guilty expression was identical to Gazebo’s. “Don’t worry, let’s toss the soiled papers,” I said. “David will never be the wiser.” He wasn’t. Now it can be told!

Though he was solitary as a child, and always sort of occupied a one-man universe, he was also intensely social, what Samuel Johnson called “clubbable,” even with people he’d never met before. Many writers jealously guard their big-time editorial contacts, but Eric wanted everybody to get in on the writing party. “Eric knew everything about the city,” says Seattle Times reporter Paul Roberts, who worked with him at the Weekly from 1988-94. “He was also quite generous; I remember once hearing his phone ring while he was on deadline. It was an editor from The New Republic, asking if Eric had any idea for stories about Seattle. Eric, being busy, looked around the newsroom, saw me at my desk and forwarded the call to me, which resulted in my first national news story.”

He was incapable of being boring, or refraining from relating his latest journalistic discoveries. He was a Weltburger, a citizen of the world. At six, his professor dad took the family to Vietnam for two years. He poetically remembered the women in traditional garb: “As they bicycled past, the tails of their ao dais fluttering in the breeze, they looked like flocks of butterflies riding the breezes off the Saigon River.” Half a lifetime later he returned and wrote beautifully about it in The New York Times.

His first important Seattle job interview, to be the business editor of The Argus, a weekly founded in 1894, was awkward: the publisher kept asking him about Seattle arts. He’d written a thesis-like paper on Bellini’s Saint Francis in Ecstasy, which he called “the European painting that first fully embraced the wider natural world,” and he’d picked up enough about local artists to talk about them intelligently. Turned out there were two jobs open, for business and arts editors, and the publisher thought he’d applied for the latter. They shared a laugh, and the wily skinflint hired him for both jobs, at one salary.

His Argus colleague and lifelong friend Candace Dempsey sums him up: “Tall and goofy, a man of many languages, endlessly curious, restless, bright, able to fit in anywhere and talk to anyone.”

At the Weekly, he pitched a story, “The Unknown Internees,” which no one else ever would have pitched to a Seattle editor. Recalls our colleague Rebecca Boren, “He took an apparently unpromising and definitely obscure subject, the internment of Aleutian Islanders by our own government during World War II, and by sheer determination (and relentless talk) sold Weekly editors on the story.” The paper had started to sell scads of ads and had acres of pages to fill, and suddenly a zillion words by Eric about his self-financed sojourn with the Aleuts sounded terrific.

It was a ripping read, and it earned him honors from the Robert F. Kennedy Foundation — he regaled Ethel Kennedy with Alaskan lore at the dinner — and a $5,000 Livingston Award. “I believe Ethel Kennedy said something about Eric’s story being the work the prize was created to acknowledge,” says Boren. “Eric took considerable satisfaction from the fact that his $500, reluctantly published, freelance piece won a major national award — with a $5,000 prize, at that. That would be $15,747 today; my Seattle rent then was $185 a month.

He also won awards from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and at that awards banquet he bonded with an editor who liked his writing about elephants — he’d been smitten with elephants in Vietnam, and wrote about Seattle’s zoo pachyderms. This led to his brilliant first book, Seeing Elephants, which opened our eyes and minds to their wonders.

Looking at Michelangelo’s David got him thinking about the Italian marble quarries the sculptor used, where Eric’s relatives still lived, so he spent years writing the astoundingly personal and exhaustively researched book Michelangelo’s Mountain: The Quest For Perfection in the Marble Quarries of Carrara. In recent years he became an expert on the environment. He wrote The Big Thaw: Ancient Carbon, Modern Science, and a Race to Save the World, which won four major prizes including the Washington State Book Award. “He had evolved into a science/climate writer of extraordinary lucidity,” says his friend, writer Joel Connelly, a man of sky-high standards.

“You couldn’t spend time with Eric without learning something,” says our Weekly colleague Jane Adams. “His curiosity was stimulating, wide ranging, and infectious.” He was a born reporter. When Eric and I took a three-week junket to Thailand, he decided to stay in Bangkok for a while instead of leaving with our journalists group, because he’d gotten a fascinating story lead. When he caught up with us in Phuket in the middle of our briefing by a local hotel rep, he asked about the controversy over the hotel’s policy of restricting its beach to guests, whereas Thai law or tradition held that beaches were open to everybody. The hotel rep did not appreciate Eric’s instant expertise, but we appreciated his bold curiosity.

Another reason Eric spent more time in Bangkok was that he was recently single, and he’d fallen in love with a high-IQ woman, not for the first or last time. His absentminded charm did not desert him in age, reports his friend, photographer Joel Rogers. ”I was and still am amazed at Eric’s drive and diversity,” says Rogers. “One aspect of this is how sexy he was. Yes, Eric. Three of us very middle-aged men sat in on a set of music at the MoPop, verging on boredom, we being clearly the oldest in the crowd.”

At MoPop, recalls Rogers, “Eric took out a small pad and began sketching two 20-something ladies. I did not know he could sketch that well, he had caught their characters in a few strokes. He walked over and showed them the sketch and they were totally charmed, and I swear, he could have taken them home.”

I once took Eric to a Seattle club at the dawn of grunge when the baristas we used to buy lattes from at Raison d’etre were about to become Pearl Jam, but I couldn’t get him interested – “Too same old, same old.”

But he never stayed home for long. There was always another adventure. Jeanne Kohl-Welles said on Facebook, “Alexander Welles and I got to know Eric in 1987 on a trek to Macchu Pichu from Cuzco over the Inca Trail. Alex and I got lost with two others and had to be rescued late at night. It led to an article by Eric and a three-part KIRO-TV special, “Lost in the Andes.” Quite the adventure! We really enjoyed getting to know Eric.”

He had a few dangerous scrapes himself. The memory of one ride on top of a bus in South America over incredibly potted mountain roads still amazed him — he had to hang on for dear life. Boren remembers his 1980 hiking and whitewater rafting expedition to Peru. ”He admitted to accidentally swallowing river water, despite dire warnings of various parasites. When he finally sought medical care, his doctors couldn’t believe he was out of bed, let alone working. There was pneumonia, parasites, I think dysentery. He finally admitted, in laconic Eric style, that he definitely felt sick. For a skinny writer with a stammer, Eric sure was tough.”

As an editor at the Weekly, I once demonstrated that a staggeringly well-informed review of The Name of the Rose by George Weigel, future biographer of the Pope, was too long, because I could use the galley as a jump rope. Eric wrote much longer than George ever did, and it was easier to get Gazebo to surrender a bone than to get Eric to part with a single one of the fascinating wonderful facts he’d discovered. Assessing the Michelangelo book, Paul Robert Walker, author of The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance, hailed Eric for “his strong, polished, yet informal prose — reminiscent at times of the marble he describes.”

Here’s how Eric described marble: “‘Living stone’ is a concept that resonates deeply in Italian culture. At its most mundane, it means the rough, uncut stone used to build castles and farmhouses. For the cavatri, scarpellini and scultori it meant fresh, vivacious stone newly cut from the mountain, still dense and resilient, with its crystals still twinkling and translucent, before the marble ‘sap’ drains from it and it becomes cotto, ‘cooked,’ brittle and breakable; in old Florence, sculptors were called ‘masters of la pietra viva.’ And at its most exalted, pietra viva is the invocation sounded by Saint Peter, the rock on which Jesus built his church:…’Let yourselves be built, as living stones, into a spiritual temple.’”

Facts were sacred to Eric, and his writing was crystalline, twinkling with wit and erudition. It’s like living stone — it’s vital, and it lasts.

He was about to go skiing with Dempsey after his Galapagos trip. “Right before he left, I saw him at a Solstice party,” she writes. “A bunch of us were talking about death in the outdoors, what risks were worth taking. I said risking your life had to be on a major adventure — otherwise you look foolish. I recounted several stupid things I’d done on minor peaks in the Cascades. If I’d died, nobody would have been impressed. He mentioned some cars that broke down or ran out of gas at the worst times, in obscure places. He was famous for that.

“We were drinking red wine and just kidding around. Everybody had a story. He lamented the fact that he’d forgotten to bring a bottle, and I said, ‘Oh, nobody cares, Eric. You’re so much fun.’”

I know he didn’t want to leave his wonderful daughter Kate, his siblings, his friends, his many writing projects. ”Eric told me he always had at least three books in various stages of completion on his computer, and I wish we could have read what he would write next. Asked if he had ideas for more books in 2011, he told Seattle Wrote: “Enough ideas for a Methuselah’s worth of years. I hope to realize the best of them; figuring out which those are is the hard part. Not to mention the known unknowns of publishing’s future. My last editor told me, ‘Hurry up and write another one while we’re still publishing them.’”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you, Tim, for that engaging profile and remembrances. Eric was an original. I will always remember him, and his insistance that porter was the perfect accompaniment with oysters at the old V.I.

What horrible news! We just saw him a week ago zooming in from the Galapagos for a fleeting visit to our weekly Post Alley newsroom meeting. What a loss for everyone who knew him and the worldly perspectives he brought into our lives through his writings. RIP.

A worthy remembrance, Tim. Such a loss.

Loved Eric’s volunteering for the NW Science Writers Association, a nonprofit that he supported. That’s how I knew him, mostly as he gave mentoring to others and shared details of his publishing adventures.

https://nwscience.org

I am just blubbering at this loss. I’ve known Eric since the late 80s, and adored him as a super fan girl, despite my need to remain at least somewhat professional when we talked about potential stories. After reading this incredible obituary, now I understand all the reasons why.

A beautiful, beautiful piece, Tim. You and your colleagues did Eric right.

Tim, that’s a wonderful piece, and captures Eric so well. Thanks for this: “He was like the electron in Bohr’s model of the atom: not to be found on a predictable orbit, but rather at any moment somewhere in the universe on a cloud of probability, with Seattle as his orbital shell.”

Conversations with Eric were always memorable. One I remember particularly was when we bumped into each other on the street near Freeway Park and stood and talked for 20 minutes about city politics and elephants and giraffes, because that’s Eric.

Another was less comfortable. I was on the board of an organization that was involved in a minor contretemps (okay, maybe it was more than minor) and Eric called me to get some details about the story. Even though we were friends, he showed no mercy. He kept peppering me with questions and I kept dodging, or trying to. As a fellow journalist, I had to admire his persistence and professionalism, even though it was at my expense.

At the end of our conversation, I was whining that this was the first time I had ever been on that side of that kind of phone call, and it was definitely no fun. He laughed and said, “Well, try to stay out of trouble.”

What a loss and tragedy his death is. And what a lovely guy he was, even when he was trying to crowbar a quote out of you. Thanks, Tim, for giving him the beautiful tribute he deserves.

Thank you Tim, for this wonderful recap of a writing life. I admired Eric tremendously and felt honored when I finally had a chance to edit a few of his stories, not that they really needed it. I always assumed we would have more chances to hang out, some day.

Thank you Tim, a brilliant piece of writing, and a daunting task to compose I am sure. Eric was/is one of the great human beings. I’m not seeing a point where he won’t be missed.

I never met Eric, but I am a lifelong admirer of his writing, including of course, the pieces he wrote here. Great sense of humor; too. What a sad loss! Thank you for this beautiful tribute.

I’ve been re reading Eric Scigliano pieces…. his beautiful series about the Fraser River, the scorn he poured on J.D. Vance and Trump for their Haitian dog-eating lies….out of all these, I’m especially struck at his vigorous but exasperated voice in “The Case for White Roofs” (which was news to me).

“So we drive our thirsty SUVs, fly far and near, gorge on steaks and burgers, install dark roofs, and crank up the air-conditioning—even when climate-friendly and budget-friendly alternatives are available. If business, government, and consumers can’t get serious about this small piece of the climate crisis, how are we ever going to deal with the whole looming catastrophe?”

His early death is such a loss. I never met him, really had no thought of it, but I feel we are poorer without him.

Thank you for writing this beautiful peice about my uncle. He was admired and inspired by many of my family members.

Brian and family and Eric’s family of journalists: our heartfelt condolences to all of you. You are all in our thoughts. Here in the south end, Eric was part of the fabric of our everyday lives – ever present at the dinner table and present for our kids now young adults.

I had the honor of having your uncle as a writing professor at a grad program at the UW, in the early 90s. Somewhere, I have a copy of this really sweet compliment (written in green felt pen), on one of my pieces. Let’s just say he was very kind/gentle about his criticism. That meant a lot to me. Many years later, he edited a piece I wrote for Seattle Met, about writing myself onto a Tennis Reality TV show, that appeared on the (then) Fine Living Channel. (Again, edited it with grace and presence.) He also was the recipient of “The Darrell Bob Houston” award (my gonzo writer dad), that was started by the late Tom Robbins, and presented at the Blue Moon tavern, each year. Either way, some friends last night were talking about Vietnam (and I thought of him, bc I marveled at how he spoke it, fluently), and I looked him up this morning–as was wondering what was his latest adventure–and came upon this heartbreaking, albeit beautifully written, tribute. My deepest sympathies to his family.

Wonderful tribute for a kind and brilliant man.

Thanks Tim for sharing your heartfelt memories of Eric. I’ll miss his eloquent writing and his humor. He was a dynamo. In sympathy.

Such a lovely obituary — it makes me even more sad.

A total shock. Our paths crossed professionally in the 1970s and I had no idea he was such a kid – “Only” 71 at his death. So tall, stringy, funny and smart in my memory. Oh, the Elephant book! Having known both Phil Bailey and Eric, it has always been a mind-boggle to imagine them working in the same room, much less in print at the same paper. Of course Bailey signed the checks, so that explains how that happened. On the other hand, Scigliano was what editors Brewster and Skip Berger deserved! I’d never heard the pet defecation tale before. Tim gets praise for this great tribute to Eric, a unique observer of our world.

I will miss knowing that this brilliant, kind and fascinating man still roams this planet, restlessly following where his quirky and probing mind takes him. Dear Eric, I won’t wish a peaceful rest on you, as that no doubt would bore you silly. Carry on, in whatever form that may take.

Thank you, Tim, for this complete and intimate tribute of our co-worker and friend. All the little moments I remember as we all worked together from building to building along the waterfront are what I remember best but you have made his history whole. What a true pleasure it was to have him with us.

What a terrific tribute to our late, great friend. He was indeed clubbable (thank you for that reference!). So many people knew and admired him only through his words; we who were lucky enough to know and experience Eric himself are deeply shaken by his untimely death.

Thank you for the beautiful tribute, worthy of the man. I had met him only once, in 1999, when he worked for the Weekly. The Olympic Pipeline Explosion had happened on the same day that all the computers at Microsoft in Redmond had crashed because of the Love virus. I’m a (retired, now) librarian and looked into a possible connection. I went down to the Weekly office, with all my print outs of industry articles and turned them over to him. He took my speculation seriously and used it to write about possible future dangers in centralizing energy transmission. Reading his obituary this morning in the ST brought tears to my eyes – just from that one, decades ago, meeting.

Beautiful job, Tim, but I’m still stunned by the very sad news…

Thanks, Tim. So well-said. Eric was such a terrific colleague back in the Weekly days, even for those of us on the other side of the wall. He never busted our chops as sometimes occurs between editorial and advertising. But as he once pointed out to me, he never reviewed a restaurant either. He was so funny, entertaining, smart, and always interesting. I’m glad I got to see him recently and catch up a little. I still can’t believe he’s gone.

Ellen Cole

I so enjoyed reading this piece about such a singular personality and gifted journalist. I’d been thinking lately that I hadn’t seen or talked with him for quite awhile and should contact him. Then it was too late. Very sad.