The large, ambitious Poke in the Eye exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum (through Sept. 2) is an exercise in historical revisionism, making the case that Northwest artists have been unfairly excluded from the Funk Art movement, historically associated with the Bay Area.

The curator, Carrie Dedon, has mined SAM’s back storage for pieces to make her case. Given that “Funk” was more an art-historical concept than a coherent movement, the 100-odd works play together quite nicely. The show has humor, highly evolved craft, and a general sense of irreverence. Funky dogs are much in evidence, along with funky frogs, and one gorgeous glistening funky pig – the last set of animals by California Funk pioneer David Gilhooly,

The hands-down star of the show is an enormous sculptural installation by local artist Jeffry Mitchell, a piece that has only been on view one other time in the 30-plus years since its creation. Nominally inspired by the James Ensor painting “Christ’s Entry into Brussels,” Mitchell’s Savior is a Bozo the Clown figure hanging from the ceiling, arms extended in a gesture of what might be welcome or surrender.

Behind the colossal clown, whose hands feature bloody stigmata, is a wall-mounted cheering section of hundreds of miniature paper mâché clown heads that are bug-eyed, tongues extended. I heard at least one museumgoer laugh out loud upon catching sight of the piece – how often does that happen in an art museum? Given its complexity (and fragility), it might be many more years before the work is on display again.

Dedon creates many inspired CA/WA pairings. The cartoony Wild West canvases of the prolific Eastern Washington artist Gaylen Hansen clearly share some essential DNA with the baroque extravaganzas of California painter Roy de Forest. What Hansen does with lively, gestural paint, de Forest accomplishes with all manner of canvas accretions – beads, balloons, hoses, and puppets, among other things. Both artists are essentially satirists, creating a world of anthropomorphic animals sharing the stage with their outmatched human counterparts, turning the narrative of man vs. nature on its head.

Clay art, a favorite medium for funk artists, well outnumbers the paintings on view. It was not so long ago that ceramics were seen purely as a craft, put to the service of creating useful objects like cups and bowls. All that changed in the mid-’50s, and remarkable work followed, with both Seattle and California leading the charge.

SAM is fortunate to have several signature works by California artist Robert Arneson, considered the most important ceramic art pioneer. Both his spectacular and hilarious self-portrait bust on a Roman column, and his scatological ceramic toilet, show Arneson at his witty, confrontational best. If any artist embodies the spirit of the artistic counterculture, it is Arneson.

Dedon gives us full opportunity to appreciate the work of Arneson’s clay contemporaries in the Northwest. There are over a dozen works by the late UW professor Howard Kottler, ranging over several decades and representing a wide variety of approaches. A glittering, metallic glaze creates a preciousness that wittily contrasts with the strangeness of the abstracted figure sculpture, “Kottler Posing as a Cubist,” along with a fire engine red dog nuzzling an emaciated red skull in “Skull Doggery.” “Baroque Braque” imagines a Analytic Cubist painting as it might look in three dimensions.

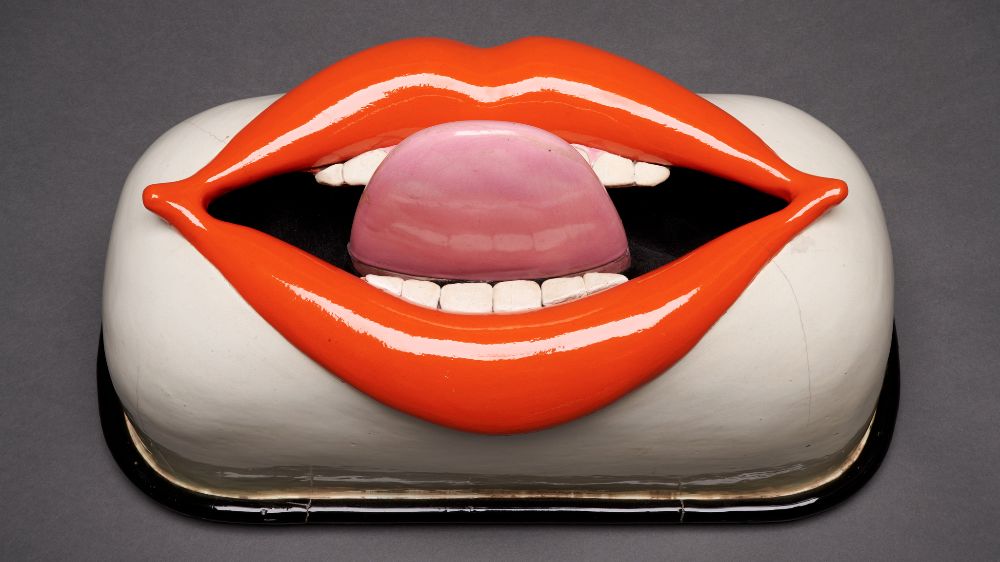

Very different in content, but equally playful and imaginative, are the dozen-plus pieces by Seattle ceramic artist Patti Warashina, who is represented by early works, quite different from her current focus on stylized figures and animals. Here she grafts surprising extensions onto various loaf-like shapes – turkey legs, a leering tongue, dimensional heat waves – a nod to the low-art references beloved of the Funk crowd.

Many visitors will be unfamiliar with the work of Fred Bauer, a close associate of Warashina and Kottler, and their equal in craft and invention. His Rube-Goldberg-machine-gone-mad construction “De-Funkt Pump” – its title revealing its pedigree – adds to its ceramic core an array of rainbow colored twisted neon tubes to suggest motion and energy, all in the service of doing who knows what.

Dedon takes pains to include BIPOC artists who were never included in earlier rosters of the Funk movement. Former Portland resident Robert Colescott, described by Wikipedia as having “transgressive humor and an explosive style” – a perfect fit for Funk – is represented by several paintings. One is a funhouse version of Susanna and the Elders, in which the artist himself joins the traditional two men (one a black janitor) ogling a Jane Mansfield beauty as she emerges from a hotel bathtub.

African-American, Seattle-born artist Xenobia Bailey is a self-described member of the funk art movement, working in a style that she has dubbed “Funktional Design.” The entire back room of the exhibition is devoted to her work, a celebration of the art of crochet. The artist surrounds her show with dark blue wallpaper filled with stars, crowns, and a life-size, god-like figure. The room itself features several mannequins and a giant tent, all draped in an array of colored crocheted fabric. Her work, according to the artist, is an homage to the African culture which slavery violently shattered.

But besides its aesthetic and polemical qualities, the Bailey room suggests an issue with curatorial classification in general. If Impressionism is a label that no two art historians can agree upon, Funk falls into the same category. Impressive as Bailey’s work is, it lacks the humor, exaggeration, and irreverence so dominant elsewhere in the exhibition. It deserves its own show.

The good news is that the iconoclastic spirit which animated the exhibition artists back in the heady days of drugs, sex, and rock and roll, persists in the culture at large (i.e.: Fremont’s naked cyclists), all the more important in our anxious and uncertain age.