Growing up an Army Brat, it was my fate to meet a great many people whom I never would have met growing up more conventionally. One of those to whom fate introduced me was Mary Alyce Kerner.

When we became unlikely girlhood buddies, our fathers were both officers in the U. S. Army stationed at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. My dad was a lieutenant colonel overseeing the metereology school; Mary Alyce’s dad Major Otto Kerner was working as a judge advocate.

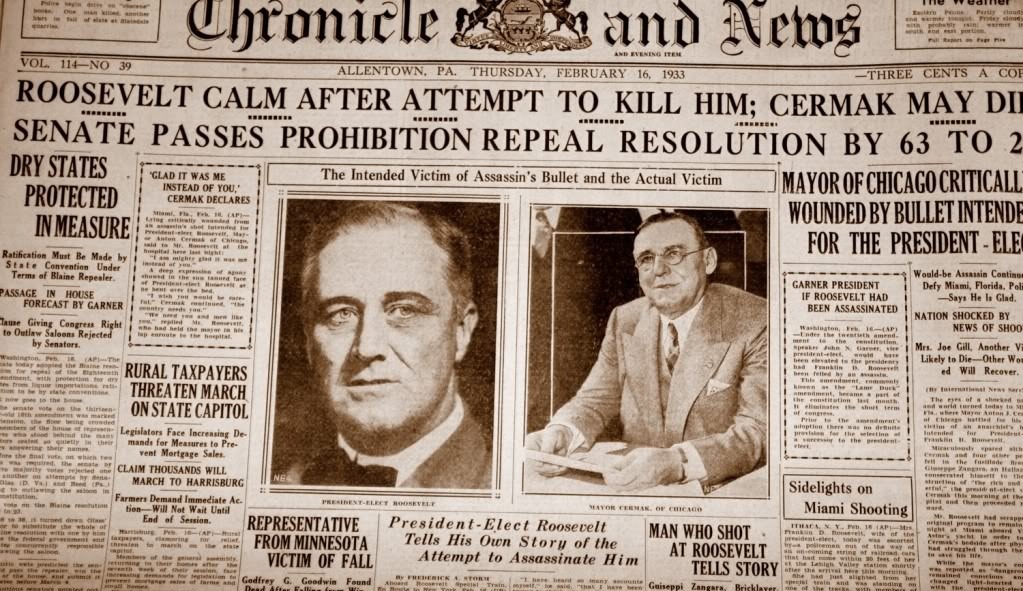

More interesting to this story, is that Mary Alyce’s grandfather was the late Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak. In 1933, the mayor had traveled in Miami to meet with President Franklin Roosevelt to mend fences and seek his help in meeting Chicago’s financial shortfalls.

The two powerful Democrats were chatting in FDR’s open convertible when a would-be assassin, Giuseppe Zangara, fired a rifle intending to hit FDR. The unemployed bricklayer’s arm was jostled by a bystander and Zangara’s bullet instead struck Cermak, tearing into his lung and liver. Taken to a Miami hospital, Cermak lingered, dying of sepsis 19 days later. In his final days, Cermak is alleged to have said to FDR, “I’m glad it was me and not you.”

At the time Mayor Cermak’s death, his daughter Helene, a young widow, was newly married to Otto Kerner, a rising Democratic star. Kerner had adopted Helene’s infant daughter Mary Alyce. When World War II broke out, Kerner served valiantly, earning a Bronze Star for merit and a Soldier’s Medal for rescuing a fellow soldier from drowning. Major Kerner’s time in active service was coming to a close when he and Helene arrived at Fort Sill.

In any other universe, it was unlikely that the pair of us, both 13-year-olds, would become friends. Mary Alyce had been born into the semi-royalty of Illinois’ Czech immigrant community. That her mom Helene was used to a different lifestyle was evident when she complained to my family that no one had come to call on her.

Because our families were both housed in officers’ quarters on the Fort Sill base, Mary Alyce and I were bused into nearby Lawton, Okla., to attend eighth grade. Although it was a mismatch, we became pals, shared secrets, and had occasional “sleepovers.” Mary Alyce had previously lived in the luxury of a lakeside Chicago apartment and wore designer clothing. I wore a pre-pubescent bra from J. C. Penney’s; Mary Alyce had handmade lingerie fitted to her blossoming curves. I had just discovered boys; she’d already had a friendship with a Chicago classmate. She was happy to fill me in on facts of life for which my mom had given me only rudimentary details.

Years later, when my family was passing through Chicago, we caught up again. I was about to enter Northwestern as a freshman and the strikingly beautiful and more mature Mary Alyce surprisingly was already married and expecting a child.

My mom and I were invited by Helene Kerner to the Cermak family’s summer residence in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. By then, Otto Kerner, sometimes called “Mr. Clean,” had been appointed U.S. Attorney in Chicago. Meanwhile, Helene was presiding over remains of the Anton Cermak’s political machine. At the complex, we were waited on by Czech family retainers. It was as if we’d entered an unfamiliar country without a passport.

Not much later, Otto Kerner would run for and become Illinois governor. Following the urban riots of the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Gov. Kerner to head a commission to investigate root causes. The Kerner Commission famously detailed how the nation was divided into two worlds, white and black, equal and unequal. The Kerner Commission report called for enormous changes to address conditions that led to the riots. They asked for 2 million new federal jobs, 6 million units of affordable housing, and an overhaul of the welfare system.

Over the years I occasionally heard about the Kerners and Mary Alyce, leading lives far different from my own. Mary Alyce and her husband went on to have a second child. Soon after the young mother tragically was killed in an auto accident. Otto and Helene Kerner adopted their two grandchildren, Anton and Helena, who went to live with them in the governor’s mansion.

If there is an end to the story, it is again a tragedy. President Johnson appointed Kerner to the federal appeals bench. But earlier as governor, Kerner had invested heavily in a racetrack. Subsequently he was found to have incorrectly paid taxes and was revealed to have accepted racetrack stock in bribes. Certain of conviction, Kerner resigned as a federal judge before being sentenced to three years in federal prison. He was released after six months when found to be suffering terminal lung cancer.

Kerner’s missteps nevertheless did not completely obscure his legacy in human rights as governor and in civil rights when heading the Kerner commission. He was honored posthumously by the NAACP and others.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.