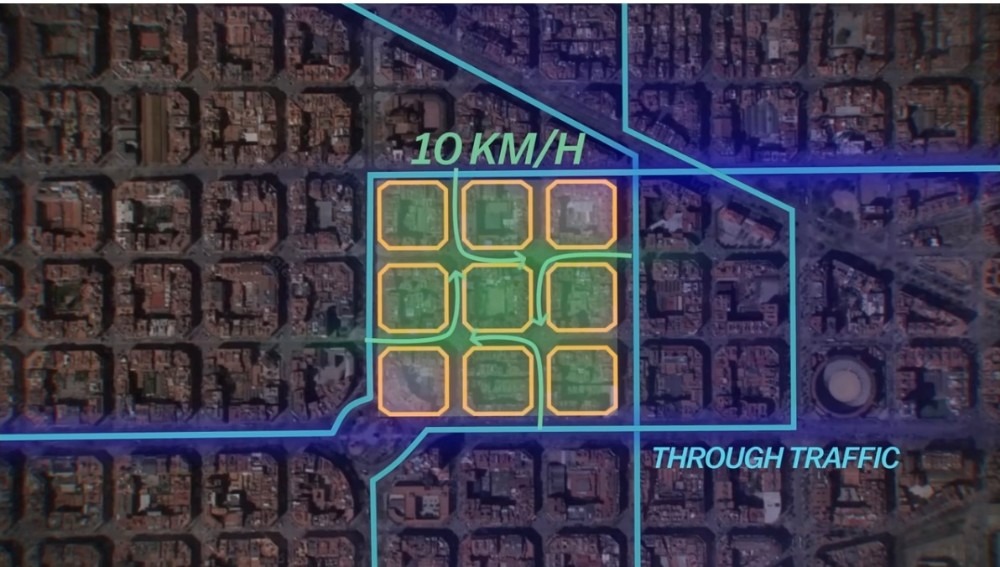

Earlier this summer, I traveled to Barcelona, Spain to learn about how the city is, once again, a leader in urban design and planning, and in particular about its “Superblocks” (Superrilles). The idea, practice, and until a year ago, city policy, was to assemble a number of nine-square grids of three by three 400-foot-square blocks, leaving the buildings in place while taking through traffic off the streets and routing it around the blocks. The 40-acre result, a small neighborhood of sorts, is low on cars, high on people, and adds plants and public space where it can.

The 2016 prototype and the Superblocks that followed have attracted global interest for close to a decade. The intellectual force beyond its current iteration, Barcelonan urbanist Salvador Rueda, has been working on the idea since the 1980s, and earlier versions date back a century, prior to Franco’s dictatorship.

As is often the case in Barcelona, there are layers of innovative ideas and practices behind its urban transformations. The Poblenou Superblock, the first one, is situated east of the city center, in a formerly industrial neighborhood whose reputation for innovation began with the turn of this century.

The transformed area was one of the first “innovation districts” of the 21st century, a declining industrial zone turned into the design-rich tech neighborhood called the “@22District.” Back then, city leaders around the world scrambled to learn from the initiative, which led to a generous volume of new, often iconic buildings, reused architecture, new public spaces, and earned its identity as a leading European city for technology-driven business.

Barcelona has been an open-air seminar for urban change for decades. Its Mediterranean

classroom is a busy one, attracting 12 million or more tourists who come to Barcelona every year. Many of them are clearly drawn to the exhilarating range of architecture, parks, plazas, squares, blocks, and boulevards that they find there. Yes, there are beaches and bars, too. Yes, most visitors aren’t on a week-long stint as I was of professional education, including interviews with city leaders and activists, as well as concomitant bike and pedestrian site visits. (I was in the Barcelona Field School/City Lab Barcelona program.)

I’ll note that in much, though by no means all of the city, we had lots of company. There were people taking in the leafy streets, strolling the bustling plazas, and craning their necks to see the curving roof lines of the wildly expressive Modernista architecture of Antoni Gaudí and his peers.

This city looks and feels like nowhere else. Barcelona makes the case for the city as a compelling place, and it is where the word “urbanism” was invented. The term was coined by Ildefons Cerdà, the engineer who laid out the hundreds of octagonal blocks of the Eixample (extension), in the second half of the nineteenth century. The square blocks, roughly 400 feet long, are eight-sided octagons because the corners are cut off, chamfered, at a 45-degree angle to facilitate modern mobility.

Barcelona also has a compelling medieval quarter — compelling today but for Cerdà’s generation it was a desperately crowded, inefficient, and unhealthy relic — as well as historic pedestrian avenues. Also, pre-dating the gridiron of the Eixample, there is the

Gràcia district, which includes one of the most compelling sequences of neighborhood squares in Europe.

The Gràcia district is where my trip started, when I was still groggy from the lost day of my life it took to get from Seattle to Barcelona. For people who idealize an intergenerational urban life of shaded streets and sunlit squares, of local shops, limited traffic, and more cafés than you can count, Gràcia is a kind of utopia. There are any number of urban districts in the world, vying for a similar reputation, boasting restricted traffic, vibrant retail, and reassuringly hostile bartenders (who make it clear they’d rather be serving the neighborhood folks).

Every square is the same but different, making a difficult neighborhood to replicate. The new Superblocks that we visited are fascinating as case studies, very appealing to visit, in places quite beautiful, and in very broad strokes they reference earlier generations of Barcelonan urban design. The difference is that they haven’t had 200 years to get it right.

Gràcia, like many places visitors admire around the world, is also at risk. Not physically, but in terms of its role as a neighborhood in the city. It doesn’t have the scrums and scrimmages of global tourism like Amsterdam or Venice (not yet), though it does have a lot of recent residents, many from outside the city, as well as short-term rentals for tourists and longer-stay visitors. Barcelonans have taken notice that their city is unnervingly popular. This July thousands marched against tourism, including scores handling water guns and squirting at presumed tourists in the much-visited waterfront neighborhood of the

Barceloneta.

Officially, Barcelona’s past and current municipal administrations have tried to balance the city’s spectacular success at marketing itself as a destination for tourism and investment against the housing costs and broader quality-of-life challenges for its residents. In response, there have been moratoria on new hotel rooms, elimination of illegal short-term rentals, and now there is a move to get rid of all of the short-term rentals to tourists in a few years. A telling example of the city’s balancing act is the bike-share program, explicitly for residents only and off-limits to visitors.

There are plenty of other ways to rent a bike, though, and I found bikes a good way to visit the city – everywhere from the Barceloneta (indoor dining recommended), cycling along a beachside bike path between towering palms, or on the protected lanes (and some very exposed and frightening ones) in Barcelona’s very busy streets, full of cars and motorcycles. Whether residents talk in terms of children’s health, biker safety, or even United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, it’s easy to understand why some Barcelonans are drawn to the traffic-calming approach of Superblocks.

After biking across the city, mostly on protected lanes, I found it a relief to finally arrive at the Poblenou’s Superblock. We sat outside at a café, with a playground just beyond, set on one of the “chamfer” spaces left between the right-angled intersection and the 45-degree angle block-front. We were in the heart of the nine-block area, with most through traffic removed with the exception of a bus route. There was a range of uses visible from where we sat, from housing to offices and museums.

We weren’t at the edge of a park — unlike Savannah, there isn’t a green square in the center block — but we were next to trees and planters, harnessing space from the oversized intersections, especially from the “chamfered corners.” There was a playground directly in front of us. Architects and mobility experts had helped to create this environment after untold hours of meetings, design, dispute, and resolution. The children in the chamfer playground looked happy. The adults in the café, who spoke to

each other rather than to their laptops, also looked happy. Our speakers were proud of their work. And yet, as we learned throughout the program, this Superblock, and the ones that have followed — even with the official support of a progressive mayor and city council and a formidable track record of moving the project forward — had encountered a lot of very unhappy people. Changing streets, reducing street parking, reducing traffic — these are not initiatives for the faint of heart.

We were fortunate to be learning from people who had also responded to and improved the Superblock program, including former City Council Chief Architect Xavier Matilla and Silvia Casorran, who worked with the same office with a focus on sustainable mobility and public space. They and their colleagues recognized that it needed to take on a much deeper and broader engagement strategy, explaining early and often that local traffic would almost always get through, that the nine-square idea was flexible enough to accommodate a bus route, and that it could be enlarged to a multi-block scale, to become a Green Hub, and a Green Axis.

As we learned, the city policy has evolved into one of Green Axes, articulating how these were in a network, not isolated enclaves. If the program was to move from a handful to 500 blocks, it needed to adapt and change.

The largest physical manifestation of this work is the astonishing 20-block-long portion of the Carrer del Consell de Cent, once choked with cars like much of the center city of Barcelona. It is now a green hub, a place to walk or ride a bike, sit under the trees, and to contemplate a greening program that is serious not only about its human patrons, but also about the health of its root systems. It was a classic street in Cerdà‘s Eixample grid, which has now benefited from a design competition that led to eight winning projects, four taking on sections of the street, and four with designs for the intersections.

It’s similar to a green spine with complex eight-sided vertebrae. In some cases, half of the

intersection becomes public space. In others, the whole intersection displays handsome

contemporary designs of different ratios of green and hardscape. Local traffic, at very low

speeds, is allowed, but it takes up far less of the pavement, or former pavement, than in the past. Walking it during the day or riding on it after dark is a proof-of-concept of how to occupy a city where cars are less and green is more.

Not everyone is astonished, not in the positive sense. On the judicial level, In September 2023, a Barcelona court ruled in favor of a business and tourism association against a portion of the Consell de Cent and related blocks, requiring the city to undo the work on a nine-block section because the city had not followed the required planning procedure of changing the city’s General Metropolitan Plan first.

On the political level, a new mayor and city council came into office in mid-2023, replacing the administration of Mayor Ada Colau, who came to office in 2015 as a housing activist. The Superblocks/Green Axes program, which had moved forward while weathering criticism, quickly lost its institutional support. The city formally spoke to the future of the program in May 2024, saying that due to its costs as well as “the dynamics of coexistence” — presumably a term for the challenges of meeting concerns for maintaining the status quo of vehicular access and circulation.

Are Superblocks/Green Axes canceled? The jury is still out. For one thing, the city says that it still believes in street “pacification,” and that it is seeking a new model, just not Superblocks. For another, while they briefly took down the Superblocks web site, it quickly went back up. The idea of Superblocks has champions, advocates who vote, and it is hard to reject a program that has facts on the ground on its side. The city has no intention of dismantling the work that has been done. They may have realized, too, that the public space is extraordinary, and that it is rarely a good idea to undo work done to improve the public realm, even by a former mayor. From an outside perspective, and I suspect from an inside one, too, Barcelona can seem very mercurial, running hot and cold on everything from tech to Superblocks to politics of all kinds, from autonomy and independence to tourism. I took to calling it “the city of strong opinions.” The stakes are very high. Yet I have high hopes for continuing to improve the “dynamics of coexistence.”

Barcelona gets so much done. There are always reasons, often good ones, to question urban development, from a curb cut to a city district transformation. The ecstatic reviews of Barcelona’s transformation for the 1992 Olympics were remarkable in terms of long-term urban legacies.

These gains were followed by scholarship that sensibly asked whether the public could have benefited more. The enthusiastic reception of the post-industrial transformation @22District” has been followed by questions about its focus on global rather than local enterprise and residents. Such queries, of course, might also be directed towards similar innovation districts, as in Seattle’s South Lake Union.

The paradigm of Superblocks has been rethought, even by its advocates, first into the Green Axes policy, and also in ongoing discussion and debate. Shortly after our week-long program, our study leader, Jordi Honey-Rosés, Director of City Lab Barcelona, led a workshop on the viable future of the city’s Superblocks, as a term and a practice.

From where I sit, back home in Seattle, the term and practice seem a useful approach. One reason is history, as in the Eixample grid itself, which was an idea that was turned into effective urbanism that merits respect. Barcelona builds on its urban ideas, and these ideas are also profoundly connected to a rich context of recent and ongoing work in Barcelona.

There are other types of major capital projects for public space and circulation, similar in aspiration but different than the Superblocks. In the working-class district of Sants, east of the main rail station, they boxed an active railway corridor and topped it in 2016 with half-mile long Jardins de la Rambla de Sants, a major investment in public space at a cost upwards of 100 million Euros. And for now, while time may change its context, this exhilarating belt of green seems to belong more to the neighbors than, say, New York’s High Line.

There are also street-calming, or “pacifying” capital projects less celebrated than Superblocks, yet highly attuned to community goals. On two Fridays, I rode with the bicibús, the parent-led escort of bicycling children to school, where a raft of parents, including a city council member, moved through the city, led by the parents and allies, passing people on the sidewalk who cheered them on. (Portland has a very active program like this).

When we got to the school, we saw the physical results of the “Protecting Schools” program, which through temporary tactical urbanism, applied to more than 200 school locations, providing safer spaces for children, reusing parking and through lanes. While its funding has been radically reduced, the program continues. An advocate for the program and related initiatives, the “School Rebellion,” which advocates for safer streets for schools, has met with the new administration, and is likely to pressure for increased funding.

Barcelona gets so much done, and somehow, despite political debates on every level, manages to incorporate changes only possible with grassroots support, debate, and major public financial support. If we can glean that from them, along with a few ideas on food and architecture, that’s more than enough to learn from Barcelona.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I just came to the conclusion that what sets great urban cities from the mere mediocre is the ability to stroll. Whether it is Barcelona, Rome or Paris, at the end of each day I’ve checked the number of miles walked and always pleasantly surprised myself. So at the end of a week or two in Europe, I find myself fitter even though I’ve enjoyed a glass or two of wine at each meal.

Here is Seattle, we could do with some re-visioning and re-imagining of the Olmstead brothers network of boulevards. What can we do to make that network more amenable to walking and strolling? What can we do to interconnect neighborhoods with streets and thoroughfares that are enjoyable to walk along and not just the most convenient way to get from point A to point B where one needs to put up with car noise.

Mexican cities have a tradition of blocking off their main streets in the Central Business District for pedestrians and bikers on Sunday mornings. Something like that could easily be done from Pike Place Market through Belltown, or on Broadway on Capital Hill, or on King Street in the ID, or on California in West Seattle, or between Westlake and Seattle Center along 5th. In fact, I’d argue that the roadway below the monorail should be reclaimed as a pedestrian/bicycle path as much of the roadway is essentially unusable.

I walked the Camino de Santiago and looked for creating walks like it through Seattle, which took some consideration. The key is avoiding routes that require stopping at traffic lights, which mean stopping and waiting.

If you take the King Co. water taxi from the waterfront, you can walk to Lincoln Park without encountering a single traffic light. Same with walking the Elliott Bay trail from Myrtle Edwards all the way to Golden Gardens. Similar walks can be made through neighborhoods in Seattle by walking through neighborhood streets and avoiding arterials. I don’t think we need to close streets with the associated expense to find walking routes for the public.

“Barcelona gets so much done, and somehow, despite political debates on every level, manages to incorporate changes only possible with grassroots support, debate, and major public financial support.”

Seattle’s approach to “grassroots support” has been through city “engagement” projects that are highly unlikely to yield valuable input, even when genuinely intended to. The way people really come to understand the world they live in, is by living in it, and the phony baloney drawings of people strolling around in designed spaces generate only meaningless reactions. At a community presentation some years ago for a building project that might include a retail storefront, the people’s choice for what would work there seemed to be “doughnut shop.” Because, you know, who doesn’t like doughnuts? Though the larger area supported only one marginally successful doughnut shop, in a far better location, but … gosh, now that you mention it, I could eat a doughnut right now, how about you?

Some day we may have a science that allows us to design great urban spaces from first principles, but today we simply have to take the time that great cities have taken. If a city has to be built out in 5 or 10 years, too bad about that.

We do have first principles on walkable urbanism, and if there was a graphic to show it, I would include it here.

Not to overlook the popularity of high powered scooters in Barcelona. 600 and 800 cc scooters are parked endlessly next to the curb on Barcelona sidewalks without being ticketed. We are talking row after row of parked scooters, thousands really. What a solution! And great insightful article!