Say what you will about those conservative Supreme Court justices, they certainly have a fine sense of irony. Two hundred forty-eight years almost to the day after colonial leaders announced that they were done with monarchy, the Supremes — in the Trump immunity ruling issued on July 1 — basically announced that actually, no, we’re not done with monarchy.

Let’s hope that’s not the last word. For now, though it is the word.

After Richard M. Nixon left the White House in disgrace, he said, “if the President does it that means it is not illegal.” (Nixon might well have become the first indicted ex-President a half century before Trump claimed the honor, but his successor, Gerald Ford, pre-emptively pardoned him. Nobody then thought an ex-President was immune.) At the time, most people thought that the sleazy, megalomaniacal ex-President was just saying something outrageous. Turns out he was ahead of his time. The Supreme Court has just made that clear.

The Court came up with three levels of immunity: If the alleged act involved core Presidential functions, immunity is absolute. If the alleged offenses involve no official acts, immunity is zero. In between — if the acts are official but not core — there is a rebuttable presumption of immunity. But you can’t take evidence from the core functions to rebut it or do anything else. The President’s intent, the content of protected speech — any other niceties are irrelevant.

This is an extremist decision. And, despite the high-minded expressions of concern for the Constitutional separation of powers and the potential for inhibiting future presidents, what happened to the Court’s originalism now that we need it? David French explains in a very good New York Times op-ed, in both the Immunity case and the earlier case in which Colorado tried to use the 14th Amendment to keep Trump – as a former insurrectionist — off the primary ballot, the Supreme Court majority, for all its pretense of originalism, disregarded the text and context of the Constitution to make policy choices.

French, perhaps charitably, thinks those policy choices were plausible — who wants MAGA Republicans or for that matter partisan Democrats routinely using the courts to keep opponents off the ballot or prosecuting Presidents for political gain? But the Court has no business making policy. And, French thinks, it should have been the province of someone other than the Court. The majority’s reasoning was “rooted in real concerns,” French writes, “but they’re not textual, they should not be constitutional, and they contradict the wiser judgment of the founders in key ways.”

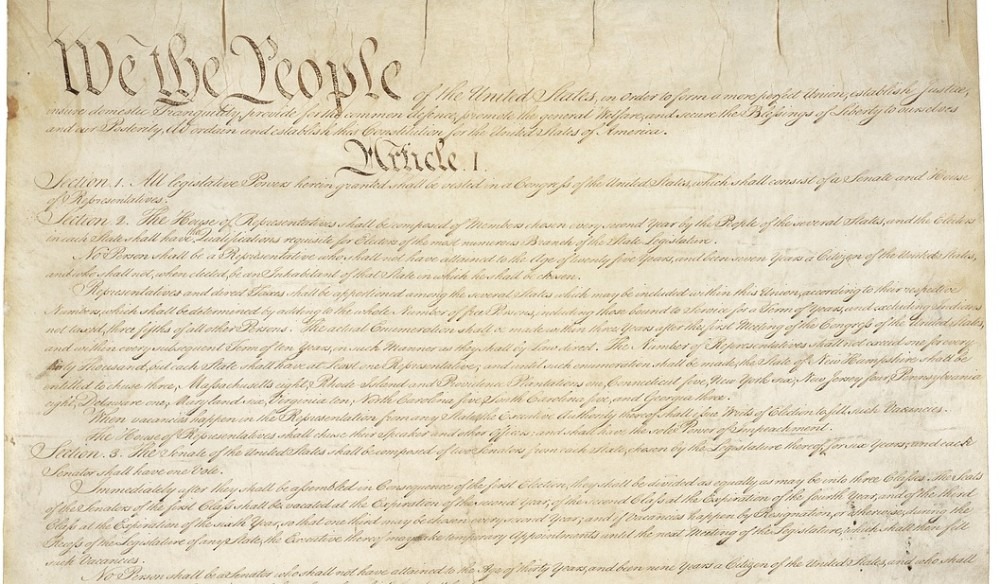

Does anyone really believe that the Framers, having rid themselves of one king, had any intention of creating another? Look at what the Constitution says about impeachment. It says that the President, Vice President “and all civil officers of the United States” can be impeached. It does not distinguish between the President and all the others. Impeachment itself carries no penalty beyond removal from office and ineligibility to hold any future office. But “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment, and Punishment, according to Law.”

That seems to mean that impeachment doesn’t give anyone a free ride from the legal system; moreover, impeaching and then indicting doesn’t constitute double jeopardy. The Constitution doesn’t suggest that former Presidents are or should be above the law. In fact, it doesn’t distinguish the President from “all civil officers of the United States.”

Don’t be fooled by the court majority’s faux-high-minded concern for the Constitutional separation of powers or the possibility that a future President would be inhibited by the prospect of prosecution.

What did they think back in 1789? Well, Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist Papers – the erudite effort by him, James Madison, and John Jay to sell the proposed Constitution to the American people (or those relatively few people eligible to vote) — that former Presidents would be “liable to prosecution and punishment in the ordinary course of law.” For Hamilton, there was an important distinction between “the king of Great Britain,” who was “sacred and inviolable,” and the “President of the United States,” who “would be amenable to personal punishment”

The President may not be so amenable anymore. During oral argument, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Trump’s lawyer, “[w]hat is plausible about the president insisting and creating a — a fraudulent slate of electoral candidates? Assuming you accept the facts of the complaint on their face, is that plausible that that would be within his right to do?” Trump’s lawyer replies, “[a]bsolutely, your Honor.” Absolutely, in effect echoed the six.

Justice Sotomayor minced few words in her dissent. One of her hypotheticals: a president “[o]rders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival?” she wrote. “Immune.”

This didn’t come out of thin air. During oral argument, Justice Alito said, “Well, I mean, one might argue that it isn’t plausibly legal to order SEAL Team 6 — and I — I — I — I don’t want to slander SEAL Team 6 – ” Here, the transcript notes, “(Laughter)”

Ho, ho, ho. Is anybody laughing now?

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

George Washington when he stepped back from reelection- “I didn’t fight George III to become George I.” Worst and most dangerous decision in history. And that is becoming a competitive list.

As wrong headed as the decision was – as this article lays out clearly – are there significant consequences? I don’t think so.

Look at what has happened so far with successful prosecution of presumable beneficiary. Did it bring him a big setback? Not a bit. Further prosecutions need to happen, but there’s little hope they will solve the problem.

Laws are for society, they need to reflect society’s standards. Political figures likewise, and when a political figure manages to convince society that he is OK, law is kneecapped. We have met the enemy. Americans need to wise up about what they believe and the standards they hold their leaders to. The law isn’t going to save us from ourselves.