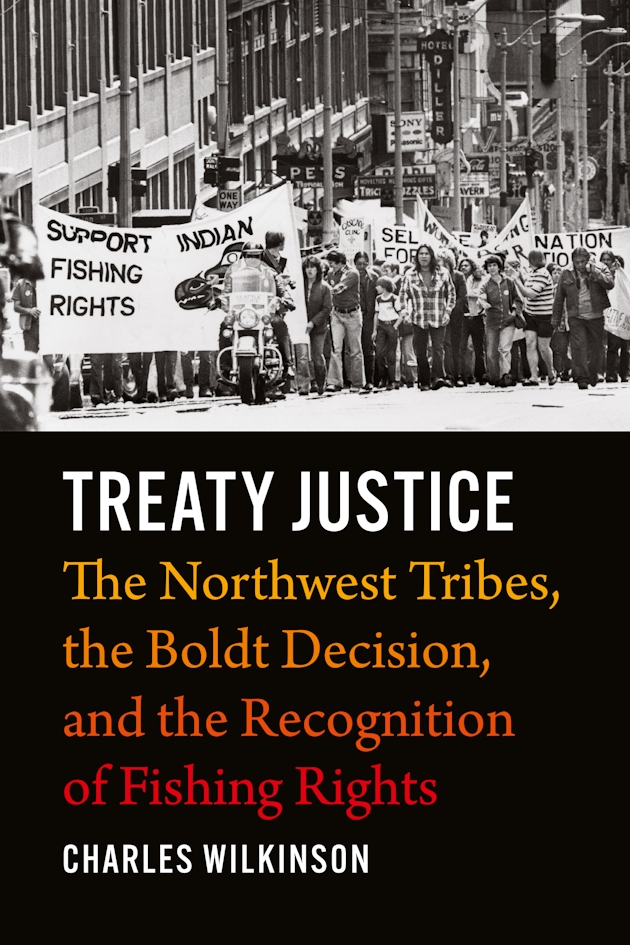

Fifty years ago, federal Judge George Boldt issued his landmark decision on tribal fishing rights. An admirable new book, Treaty Justice, by law professor and tribal advocate Charles Wilkinson, has just been published by UW Press. There are two good reasons to read this lucid book. It is an even-handed and comprehensive primer on this vexed, core issue in the Northwest. And the entire salmon saga restores one’s faith in the legal system, just in case you are needing some good news to counter today’s problematic Supreme Court.

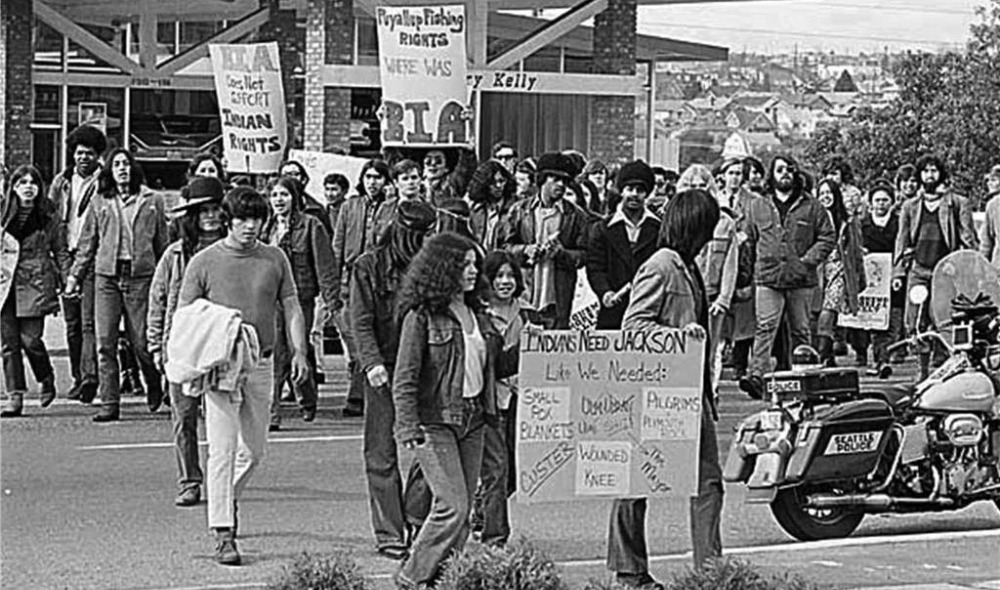

As the author states, the Boldt Decision of February 12, 1974 “vividly displays the brilliance and worth of the American system of justice and the moral and tangible benefits it can achieve at its heights.” Indeed the Court tried to end the raging Indian Wars of the times, established tribal sovereignty, and was a daring leap of faith in shared management of salmon fisheries.

It ranks up there in judicial boldness with the Supremes’ decisions about civil rights, school integration, old-growth protection, and voting rights. The lingering question is whether Judge Boldt, a crusty, conservative Montana Republican, bit off too much and escalated for years the war over salmon. It was reflective of an age of progressive judicial activism, now long gone.

The roots of the controversy lie in the numerous 1854 treaties signed by Territorial Gov. Isaac Stevens, relegating tribes to small reservations in exchange for shifting massive tribal lands to white settler ownership. The key to that lopsided trade, as Stevens (and his remarkable aide George Gibbs) well understood, was non-negotiable, namely granting of off-reservation rights for Indians to fish for salmon in “all usual and accustomed places.”

Stevens remarked at the time, “this paper [the treaty] saves your fish,” an off-hand remark that achieved salience in the court decision 120 years later. Stevens operated under the widespread assumption of the “vanishing Indian,” which assumed that tribes were destined to fade away under forced assimilation by churches and schools. Remarkably, the tribes held on and achieved a glorious vindication of their fishing rights in the good judge’s sweeping ruling.

That Boldt Decision was remarkable for its strict honoring of the literal treaty language. That ruling noted that treaties are “the supreme law of the land,” pointedly not subject to state conservation laws. Even more stunning was Boldt’s ruling that tribes were entitled not just to a “fair share” of salmon fisheries (as initially hoped) but a daring and surprising 50 percent. That meant 50 percent of the salmon were reserved for 1 percent of the state population, a ruling that really for years put salmon politics on the boil. Led by former US Sen. Slade Gorton, some tried to get Congress to overrule Boldt, but failed. The other big gamble was faith in joint (white and Indian) management of the fisheries. Both changes were fought long and hard by affected sports and commercial fishing interests, but these dramatic gambles have proved a success. The Judge’s faith in tribal traditions of wise management of natural resources was rewarded.

This uplifting story has many heroes. Judge Boldt, a remarkably thorough student of tribes and salmon, ran an admirably fair trial and threw himself unreservedly into the issues. Among the allies of the decision were President Nixon (!), Sen. Magnuson, Billy Frank Jr., Hank Adams, former Rep. Lloyd Meeds (chair of Congress’s Indian affairs subcommittee), US Attorney Stan Pitkin (a Nixon appointee who filed the landmark suit in federal court), and the six Supreme Court Justices (Blackmun, Stevens, Burger, White, Marshall, Brennan) who upheld the Boldt Decision in 1979.

Among the stalwart Republicans who held the line were Governors Dan Evans and John Spellman and state fisheries director Bill Wilkerson. The unsung hero of this legal saga was Dr. Barbara Lane, a UW-trained anthropologist who compiled comprehensive and sound reports on tribes and salmon and educated the diligent judge.

Author Charles Wilkinson (1941-2023) has written 14 books, many on Indian rights and legal issues, and served four years as staff attorney for Native American Rights Fund before becoming a law professor at the University of Colorado. It is the year of Boldt, with another notable book, Lightning Boldt by John Hughes, examining the early life of the courageous, transformative, heroic George Boldt.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for sharing the importance of the Boldt decision and its role in bringing shared fishery resource management. I just finished reading the book “In Common With,” authored by Bill Wilkerson with Don Pugnetti Jr. As you note, Wilkerson was the Director of Fisheries and forged a remarkable relationship with Billy Frank Jr. The two leaders, along with Jim Waldo, charted a course of co-management and collaborative natural resource management that extends not only to fisheries management but timber management through the Timber, Fish, and Wildlife Agreement. The Wilkinson, Hughes, and Wilkerson books should be must-reads for those who still have faith in the democratic power of good people coming together for the common good and anyone who loves the natural resources of Washington State.

This is a great book about a fascinating moment in our history. I was a pulled into the margins of this story by some friends from Montana who were involved in the fishing rights demonstrations at the time (that got pretty wild), and a roommate who was getting her degree in fishery sciences at the UW. It’s fair to say that none of us was expecting very much from Judge Boldt and were surprised and cheered by his remarkably wise and fair and bold ruling.

Thanks for this review. These days, we need some optimism about judicial wisdom in America. For that reason alone, Wilkinson’s book, and this story, deserve wider attention.