Although the American labor movement has seen better days, its traditions remain strong and those traditions in the Pacific Northwest are among our nation’s most colorful.

According to Professor Carlos A. Schwantes, an expert on Pacific Northwest labor and political radicalism, the first trade union movement in Washington and Oregon occurred in 1853 with the formation of an organization among printers. Next came organized efforts by locomotive engineers and longshoremen. In Victoria, B.C. a baker’s union was established in 1862.

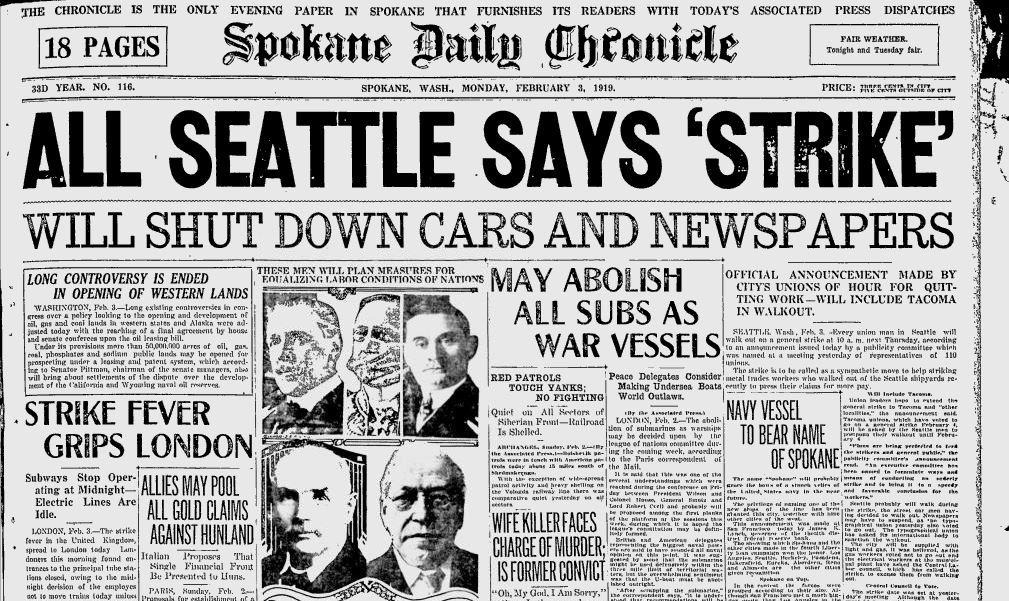

The relative isolation of the Pacific Northwest gave rise to the eastern view that our scenic new world would suppress radicalism. This view proved dead wrong in the 1920s and 1930s as radical activity, including militant union organizing set a pace for the nation. The construction of the Northern Pacific and Canadian Pacific railways in the 1880s with Asian labor caused anti-Chinese agitation among white workers, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was a direct result of this racial tension.

The Knights of Labor, with roots in Philadelphia, rose from this discontent, as did the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA). The coal fields of Washington State became an initial testing ground of labor strength. Although Sinophobia was an ingredient, a struggle over mine safety resulted in one of our region’s earliest strikes: a seven-month violent battle at Newcastle, Washington.

As the Knights of Labor and their strident methods began to lose favor, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) came on the scene. Its leader, cigar man Samuel Gompers, rightly worried that the tough, distant, independent westerners were not paying enough attention to his organization. As Gompers feared, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia labor movements were going their own way. These loose organization of the Pacific Northwest would eventually affiliate with the AFL in the early 1900s.

During the last decade of the 19th century moral reform became a cause in the Pacific Northwest. Socialists, teetotalers, cooperative and utopian colonies were all seeking idealistic answers. A number of organized labor groups and Populism linked their interests with these reform views, with William Jennings Bryan carrying their banner of free silver into presidential politics. Added to this foment was the rise of the Industrial Workers of the World – the Wobblies – who represented a kind of militant radicalism for working people. The social and political pots were boiling, including agrarian dissent. Grange halls became centers of discussion about railroad shipping costs to eastern markets.

Out of this maelstrom rose some of the strongest labor groups in the country. In time the AFL would dominate the scene, followed by the Teamsters and their Seattle-raised leader, Dave Beck.

These are quieter days for organized labor. Their time may return in another form, perhaps including trade-protection and immigration restrictions and more white-collar, tech trades.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.