“In all the earth there is no place dedicated to solitude.” So Pioneer Henry Smith recalled the words of Chief Seattle, translated on Seattle’s waterfront during the cold, clear Thursday morning of January 12, 1854. Seattle was saying that so many of his Duwamish people had lived here for so long that they were literally part of the living landscape. The white man would never be alone.

The longer we live here and the more we learn about this place, the more those words become freighted with meaning. And the more we hear ancient Duwamish voices.

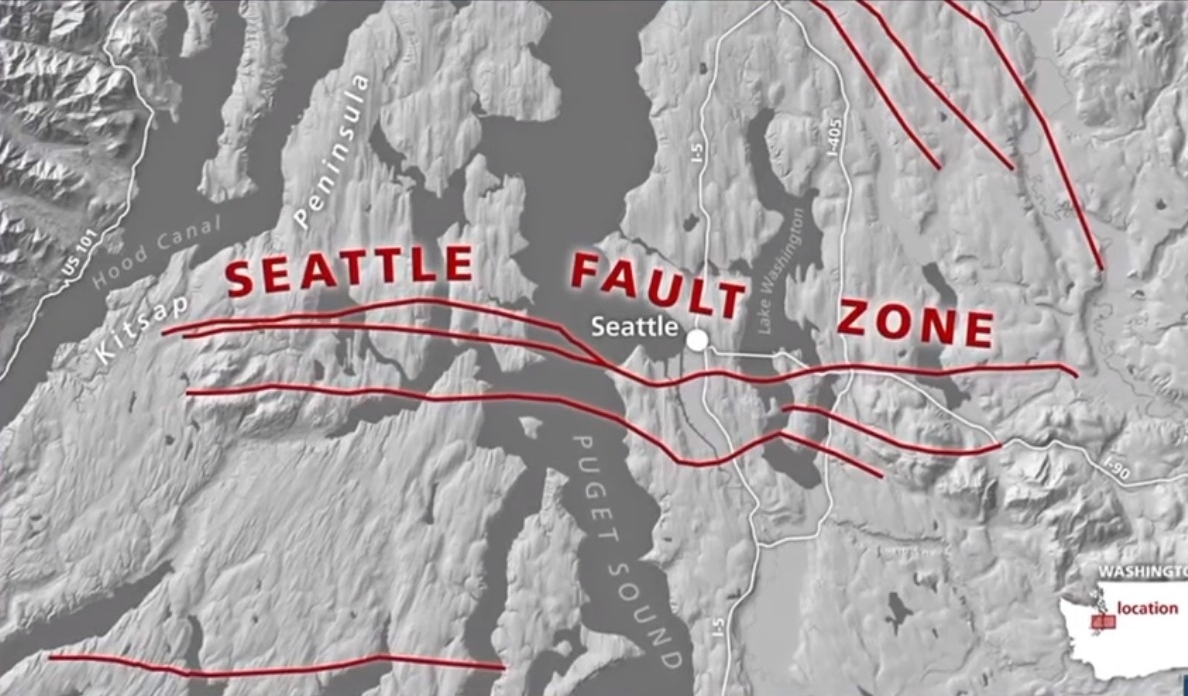

In December, 1992, five articles published by geologists Brian Atwater and Allan Moore in Science magazine, announced the discovery of the Seattle Fault, a narrow zone of faults reaching from the Olympics across Seattle and Lake Washington to Lake Sammamish and the Cascades. In a terrible few minutes sometime between the month of October, 923 AD and March, 924, land south of the fault parallelling today’s Interstate-90 rose as much as 20 feet. Land to the north dropped three feet.

The discovery was a shock and a wake-up call. If that quake happened today, the damage and death toll would be cataclysmic. A 2019 Post-Intelligencer article marveled that the quake had gone undiscovered for a millennium. But the Duwamish knew about it only too well and had shared their knowledge. A rock in the fault zone on the beach at Fauntleroy Cove was said to be so dangerous that even looking in its direction risked having one’s head twisted on one’s neck. All along the zone, from Hood Canal to Lake Sammamish, large boulders and place names warned of danger.

On December 14, 1873, at 9:40 PM, Seattle’s first Episcopal priest, Reverend R. W. Summers, stood outside his church at Third and James when he heard a sound “like the rumble of many freight trains rolled into one.” Arriving from the bay it shook the town and surrounding hills on its way to lakes Union and Washington. “The sidewalks, fences, buildings, trees all cracked and crackled like a grand discharge of Minnie balls [metal shot fired from musket rifles].”

The church yard rolled in waves “as a carpet makes, shaken with regular motions on a greensward.” Recalling several shocks in the dark, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that the motion was “like walking on the deck of a ship in a wind, and it caused nausea and dizziness. Plaster…cracked in many houses, dishes were broken, lamps tipped over.” Rev. Summers wrote that on the hills “giant firs and cedars lashed together back and forth…swaying a full fifteen feet,” as the convulsion passed over the hills to “Lake Duwamish [Lake Washington].”

On that cold, clear night Lake Union was mirror smooth, but the quake raised waves that crashed ashore, as they did on Elliott Bay. All observed that the quake traveled from south to north, radiating away from the fault. In 1999, its epicenter was on the eastern slope of Mt. Rainier; more recently it has been identified at Lake Chelan due east of Seattle. But given the lack of contemporary seismic data, the 6.5-7.0 magnitude quake may have occurred along the Seattle fault.

Duwamish folklore provides a clue. In the early 20th century ethnographer John Peabody Harrington described on the beach of Seattle’s waterfront, “two blocks up from Pike Street,” a black hole called Sh tsh pau, “Stick into, blow,” where young whales were said to travel from the bay to Lake Union. This would be under Pier 57 at the foot of University Street where its spring water once refreshed native clam diggers at the foot of Spring Street. Today th pier’s historic carousel and Seattle’s Great Wheel repeat the circle motif. In local mythology, the actions of whales caused earthquakes.

Once common in Puget Sound, humpback whales, which were 50 feet long and weighing 40 tons, when breaching vividly dramatize nature’s power. A curious behemoth doing so beside a canoe would effectively simulate the tumult and terror of an earthquake.

Long ago the valley south from Elliott Bay to Tacoma’s Commencement Bay was an eastern arm of Puget Sound. Dammed at its southern end, it was said that a trapped whale forced its way through the barrier to the sea. The barrier recalls Mount Rainier’s eruption c. 5600 years ago that collapsed the upper 2,000 feet of its summit. The colossal avalanche plunged down the upper White River valley and covered over 200 square miles of the Puget lowland as the Osceola Lahar, the largest mudflow yet measured, which filled much of the marine channel. The route forced by the whale, Stukh, “plowed through,” became Stuck River, a tributary of the Puyallup River. Whales supernaturally reshaped the land.

There is a powerful connection between the image of spirit whales traveling underground from Elliott Bay to Lake Union and the reportage of the 1872 quake: roaring movement shaking the land like a rug, sending higher waves roiling Elliott Bay and Lake Union. Add to that tall sand geysers erupting from a rift in the beach as often happens in severe quakes, leaving holes in underlying clay. The erupting geysers clinch the mythic image of whales spouting before barreling their way through the passage.

But native memory goes farther back to a greater quake still, much like Rev. Summers’ recollection of the paroxysm traveling through the hills “off to Duwamish Lake.” This one lifted land south of the fault as much as 20 feet. Lifting Mercer Island and the southern half of Lake Washington hurled lake water northward in a colossal wave. Additionally, the shaking sent mile-wide forested hillsides plunging into the lake, producing terrific waves that crossed from one side of the narrow lake to the other. The chaos scoured shores until the fury was spent.

Examination of tree rings in the wood preserved deep in the lake shows the quake happening during the trees’ dormancy between October and March. A flood of turbid sediment boiled up the Sammamish River Valley into Lake Sammamish, where another forested hillside plunged into the lake. Sediment flattened the river floodplain, slowing the current and causing the stream to meander.

Hundreds of Native people flourished beside both lakes, but the lack of myths there about the catastrophe suggests no one survived. Decades passed before the land recovered enough for kin from less affected saltwater and river villages to repopulate the lake basin. Place names along the west shore recall supernatural monsters that took people away. Another underground passage, believed to connect Mud Lake at Sand Point with the shore at Richmond Beach was how a supernatural elk carried the body of a dead hunter tangled in its antlers west to Puget Sound.

In myth, whales, monsters, and giant elk loom where the earth tore along the fault, monstrous images of monstrous power. Newcomers are still learning about the region’s tectonic dangers. The ancestors of the modern Duwamish Tribe have lived here for more than 600 generations surviving every great subduction quake, volcanic disaster, and local cataclysm. They have much to tell and teach us.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.