At long last, are Seattle’s most spectacularly successful corporate icons finally realizing that paternalism toward their employees just won’t cut it anymore? Could it be that Microsoft and Starbucks are learning the same lessons the U.S. auto industry did some 90 years ago?

Recent developments at both companies suggest they may indeed be ready to accept organized labor as part of their economic landscape.

Under pressure from employees, Starbucks recently made news by indicating a move toward “union neutrality.” Microsoft made the same pivot a few years earlier after once being labor’s poster child for regressive employment practices, including extensive use of individual contractors who received little legal protection and no benefits.

In 2022, to help clear regulatory hurdles in its $70-billion bid to acquire game maker Activision, Microsoft signed a labor neutrality agreement with Communications Workers of America. Today, the CWA represents more than 1,000 unionized workers at Microsoft, including 600 at its Activision Blizzard unit, where the company voluntarily recognized the CWA bargaining unit this month.

Microsoft’s re-think can be traced back to 2002 when Brad Smith, now vice-chairman, assumed the general counsel role. He abandoned the company’s hyper-aggressive treatment of competitors, regulators, and union organizers in favor of a simple strategy: “Make peace.”

In response to mounting regulatory pressure, Smith aimed to demonstrate concrete, progressive action, a desire to be a part of the solution rather than part of the problem. As Smith once noted, “The tech sector has often been built by founders, and founders have often been very focused on retaining a level of control over their enterprises. I think the fact that Microsoft is a little bit older, sometimes a little bit wiser, at least gives us an opportunity to think more broadly.”

Whether Starbucks has gotten religion on the value of unions, or just wants to stop their very public efforts to shame the company, remains to be seen. But the evolution of labor relations there and at Microsoft has parallels with organizing in the auto industry almost 100 years ago.

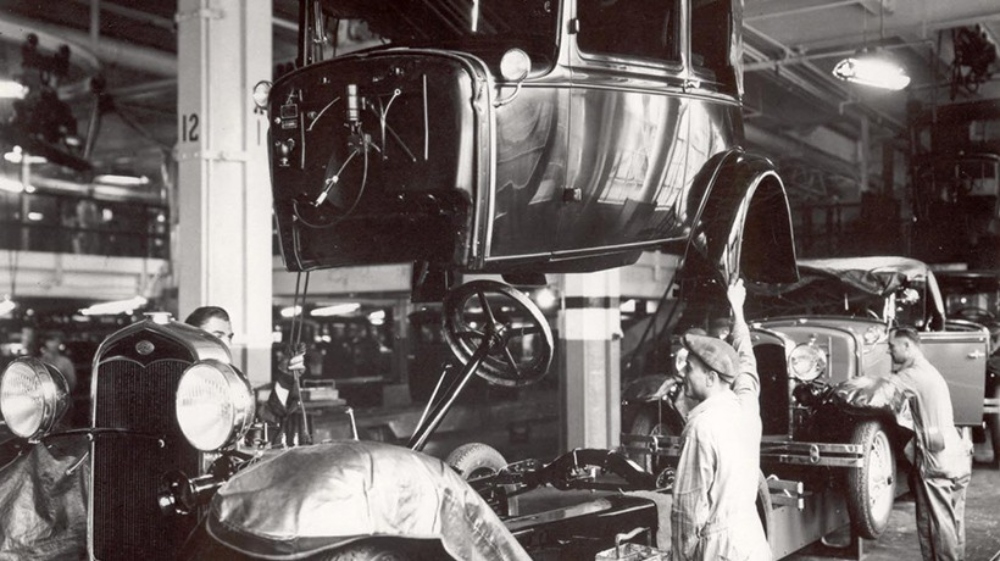

In the 1930’s, automakers too were led by founders and pioneers who were vehemently anti-union. But paralyzing sit-down strikes in Atlanta and Flint proved costly for General Motors. And fighting with its own workers was a bad look at a time when the public was already disillusioned over corporate America’s role in the Great Depression. GM executives realized that the relative peace that came with collective bargaining agreements was worth the diminished control unionization would bring.

Ford, on the other hand, persisted in its avoidance of unions, which Henry Ford viewed as a foreign invasion, a threat to the very essence of the company (an attitude not unlike that of the recently retired founder of a local coffee giant). In 1937, Ford told his son, Edsel, that union organizing would fail “because our workers won’t stand for it, I won’t stand for it, and the public won’t stand for it.”

Perhaps like more recent company founders, Henry Ford resented unions and viewed them as unnecessary because, by the standards of the day, his company treated its workers relatively well. Ford flummoxed the industry in 1914 by offering a $5 daily wage; he was first to introduce profit sharing and a five-day work week. In light of all this, Henry regarded unionization as a personal affront, an outrageous lack of gratitude.

He hired a union buster named Harry Benett and stood up the aggressive “Ford Service Department” to do whatever it took to defeat organizing efforts—which included confronting union organizers and activists, sometimes violently. But over time, even the cantankerous Ford (and as importantly, son Edsel, who was poised to assume the corporate reins) came to the same conclusion as GM had, opting for collective bargaining and relative labor peace.

The benefits for management were undeniable. Union activists had become accustomed to disrupting operations, but their new, typically three-year contracts prohibited “wildcat” strikes. When contracts expired, strikes were still in play, but subject to ground rules set by the National Labor Relations Board. This gave the process some predictability.

In another parallel with recent labor disputes, Walter Reuther’s United Auto Workers pushed for a “seat at the table” with regards to management priorities. While the UAW was never able to achieve a European-style labor presence on corporate boards, labor organizers in other industries have harnessed shareholder pressure to help change corporate policies.

Just prior to the latest Starbucks announcement, the union behind the organizing campaign, Workers United, was poised to run a small slate of candidates for shareholder board seats. The move wasn’t expected to succeed, but winning a board seat isn’t necessarily the goal. Rather, it’s to keep public attention fixed on workforce dysfunction.

It’s debatable how much the Workers United bid for a board seat contributed to Starbucks’ pivot on unionization, but the threat was one of the several layers of disruption promulgated by the union, which led Starbucks executives to decide on a new course of action—i.e., neutrality.

Neutrality is what labor advocates insist is the true intent of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. The NLRA was designed to prevent companies from organizing anti-union resistance, which often was violent, and allow employees to decide on whether to unionize without direct or implied employer threats.

That goal has never been fully achieved in the private sector. (Public agencies are typically prohibited by law from engaging in any union resistance activity.) Employers are allowed to state their desire to remain union-free, and they can order employees into so-called “captive audience” meetings to tell them why joining a union is not in their interest. The information presented in these meetings typically highlights the imperfections of labor bureaucracy and hierarchy. (Corruption is a favorite topic.)

These campaigns undermine the intent of the NLRA, union advocates say. They believe neutrality agreements simply help restore a balance, so that employees can decide whether to unionize, free of employer pressure. Which is all that principled labor leaders want.

Starbucks may be pivoting to neutrality so as to quell labor disruptions, but the result will be the same for it and for Microsoft, just as it has been for automakers and others: more unionized employment with better predictability in the employee relations environment.

If this leads to a reassessment of how labor is viewed in the economy, then it may signal the beginning of a revitalized, blue-collar middle class. And why shouldn’t “blue collar” employment allow a journeyman barista, for example, to live a decent, middle-class life? The U.S. was once flush with such good paying, non-college level jobs. If it was good enough for the “greatest generation,” perhaps it is just what Gen Z needs.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The article refers to Howard Schultz as a “founder” of Starbucks. He made the company into an international phenomenon, but he was not the founder. Those founder pals were Gordon Bowker, Zev Siegel, and Jerry Baldwin, who started the small chain in 1971, dispensing beans and coffee-making equipment (but not coffee drinks). Schultz arrived as an equipment salesman and talked the three founders into hiring him as a marketing whiz. Schultz in turn had the idea, borrowed from Italy, of dispensing java drinks, and the first one was called Il Giornale (named for the custom of consuming newspapers and a jolt of caffeine in the morning), which opened at the base of Martin Selig’s mighty skyscraper, Columbia Tower, at Fifth and Columbia. (Lattes then cost $1.10.) Schultz in 1985 left Starbucks to start Il Giornale, later rebranded Starbucks when he and local investors acquired the coffee company for $3.8 million. The rest was history.