My son recently left home for college. Afterward, I found it necessary to clean up his room a bit. Among piles of leftover laundry were also stacks of books he’d read for high school classes, including this one. Holding it in his vacated room, I remembered it had been part of my high school curriculum too, but I’d never read it. Given the events of recent years, and the Seattle Opera production of “X,” about Malcolm X, I thought maybe I should.

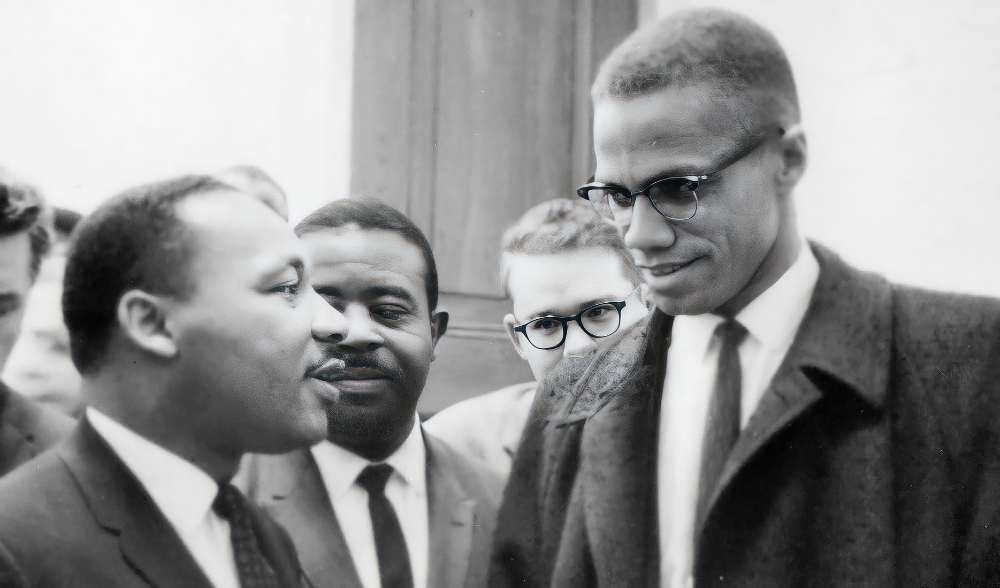

His name still evokes fear, anger, and admiration, six decades after his murder. Alex Haley interviewed Malcolm X more than 50 times from 1962 to ’65, and the result was a book alive with the same intensity as their all-night talks about racism, protest, and brutality that seem little changed since then.

Malcolm speaks to us directly in the same powerful, raw language that made him a proud militant, describing his upbringing, his crimes, his bigotry and misogyny, and his evolution into a human rights activist. He does not mince words. He does not look away. He does not rationalize his failings. Or our own. Yet he also speaks with a humility and tenderness at odds with his self-description as “the angriest Negro in America.”

“I want to say before I go on that I have never previously told anyone my sordid past in detail,” he said, and Haley wrote. “I haven’t done it now to sound as though I might be proud of how bad, how evil, I was … (But) the full story is the best way that I know to have it seen, and understood, that I had sunk to the very bottom of the American white man’s society…”

His father was a strident Baptist preacher murdered by a white gang in Lansing, Michigan in 1931 when Malcolm was 6 years old. His mother was institutionalized and the children were scattered to foster homes.

Malcolm did well in school, where he was one of just a handful of Black students. Even when he misbehaved, his white foster family interceded with the state to keep him in school. Then, when he was class president in eighth grade, his favorite teacher urged Malcolm to give up on becoming a lawyer and instead concentrate on going into the trades, like the rest of his people. He couldn’t articulate it at the time, but Malcolm felt something change inside him.

He was later expelled after refusing to remove his hat in a classroom and was removed from his foster family and sent to a reform school when he was 14. A half-sister in Boston took him in afterward. He had never seen so many Black people in his life, and they were happy and successful — within limits. He got a job as a bathroom attendant and shoe shiner at a fancy whites-only ballroom, and soon learned to hustle for his clients: bootleg liquor, marijuana, condoms, whatever. He had his hair straightened, bought a sharkskin zoot suit and scored a white girlfriend, who was married. He was 16.

Malcolm was arrested in 1946 — the only time in his life — for his role in a string of residential burglaries, a crime that should have netted a sentence of 18 to 24 months. His affair with a married white woman came up at trial, and he got 10 years in prison. He was 20. It was during his incarceration that his siblings introduced him to the Nation of Islam, which advocated Black independence from white society.

He studied the slave trade and the Civil War; he read Herodotus and W.E.B. Du Bois; Durant’s histories and Gandhi’s philosophy. “Book after book showed me how the white man had brought upon the world’s Black, brown, red, and yellow peoples every variety of the sufferings of exploitation … indisputable proof that the collective white man had acted like a devil in virtually every contact he had with the world’s collective non-white man.”

And that is what Malcolm preached for 12 years as a minister for the Nation, after converting to its unorthodox version of Islam when he left prison in 1952. Like other converts, he dispensed with his surname. “The Muslim’s ‘X’ symbolized the true African family name that he never could know.”

As his popularity grew, so did suspicion. “I’m not for wanton violence, I’m for justice,” he answered one reporter, explaining that “The white man can lynch and burn and bomb and beat Negroes — that’s all right: ‘Have patience!’ ‘The customs are entrenched!’ ‘Things are getting better!’ ”

In 1963, according to The New York Times, Malcolm was the second most in-demand speaker at college campuses and universities after presidential candidate Sen. Barry Goldwater.

The Nation of Islam took notice. “There was jealousy because I had been requested to make these featured appearances,” Malcolm said. He also learned the Nation’s leader had repeatedly violated their strict moral codes and that three paternity suits were imminent.

A smear campaign drove Malcolm from the Nation. He suspected the version of Islam he had devoted his adult life to was flawed. In 1964, he decided to make the hajj to Mecca to find out. In a life of continual change, the holy pilgrimage again changed Malcolm.

“There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and non-white.”

After embracing orthodox Sunni Islam, he became El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, but remained Malcolm at heart. “Where the really sincere white people have got to do their ‘proving’ of themselves is not among the Black victims, but out on the battle lines of where America’s racism really is — and that’s in their own home communities.”

Malcolm was shot to death Feb. 21, 1965, by three gunmen as he spoke at his weekly town hall meeting in Manhattan before the book was finished. He was 39. Three men were convicted of murdering Malcolm X. Thomas Hagan, the only one to admit his role in the murder, was paroled in 2010.

The two other men convicted always maintained their innocence. Hagan testified at their trials and subsequent parole hearings that both men were innocent and that others were involved. The two were paroled in the 1980s.

In February 2020, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office announced it would review the case, including newly declassified government and police documents, and pursue any suspects still at large. A document alleging possible NYPD collusion in the murder surfaced in February 2021.

Malcolm X said, “I know that societies often have killed the people who have helped to change those societies. And if I can die having brought any light, having exposed any meaningful truth that will help to destroy the racist cancer that is malignant in the body of America — then, all of the credit is due to Allah. Only the mistakes have been mine.”

In 1998, Time magazine ranked The Autobiography as one of the 10 most influential nonfiction works of the 20th century. It was Alex Haley’s first book. He would go on to receive more honors, including a Pulitzer Prize for his work tracing his own heritage in Roots, inspired by his time with Malcolm. Haley died in 1992.

First published in Key Peninsula News.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.