Having just enjoyed seeing “Maestro,” the absorbing two-hour bio-pic based on the life of musical genius Leonard Bernstein, I couldn’t help recalling the revealing stories told about him in Shy, Mary Rodger’s candid memoir.

Mary, daughter of the late Richard Rodgers (composer of Oklahoma and Carousel), was a close friend and co-worker of Bernstein’s. She tells us all about it in her book of “alarmingly outspoken” memories, published after her death by New York theater critic Jesse Green. Mary reports getting to know Bernstein (“everyone called him Lenny”) when mutual showbiz friends gathered during Long Island summers spent at Quoque. Theirs was a lone liberal outpost amidst a conservative resident community.

The New York expats (composers, lyricists, producers, most with Jewish backgrounds) would play elaborate word games and engage in scavenger hunts with insanely difficult clues. Mary confesses she wasn’t quite in Lenny’s or Steve’s — her buddy Stephen Sondheim’s — league. She describes them winning at anagrams by turning 10-letter words like harmonicas into maraschino.

After the successful premier of Lenny’s West Side Story, the group which also included producer Hal Prince and playwright Arthur Laurents went out for celebratory drinks. Talk turned to Lenny’s new job as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Lenny mentioned he had inherited the Young People’s Concerts which he hoped to spruce up, in part by televising them. but moaned, “What do I know about children?”

At that point, he turned to Mary, by then a single mother of three, and said, “You write for children, you know about children, you want to work on this?” Mary, who’d composed for Golden Records, Captain Kangaroo, Rin Tin Tin and others, landed the job as Lenny’s script editor, a role she would fill for 14 years. The famous first episode, “What Does Music Mean,” was broadcast live from Carnegie Hall on Saturday, Jan. 18, 1958.

She writes, “Lenny liked having a lot of people around; ‘gregarious’ doesn’t begin to describe him.” As she described it, “the production team, about six of us, crammed into a small dark studio for meetings. We would await The Entrance when Lenny would arrive clutching a fistful of yellow legal pads and make remarks on how he’d recently been treated by the music critics who were sometimes (he bellowed) insulting, denigrating, obtuse, insensitive, and ignorant assholes. Once he got that off his chest, we settled down to cutting and honing his inevitably overlong script.”

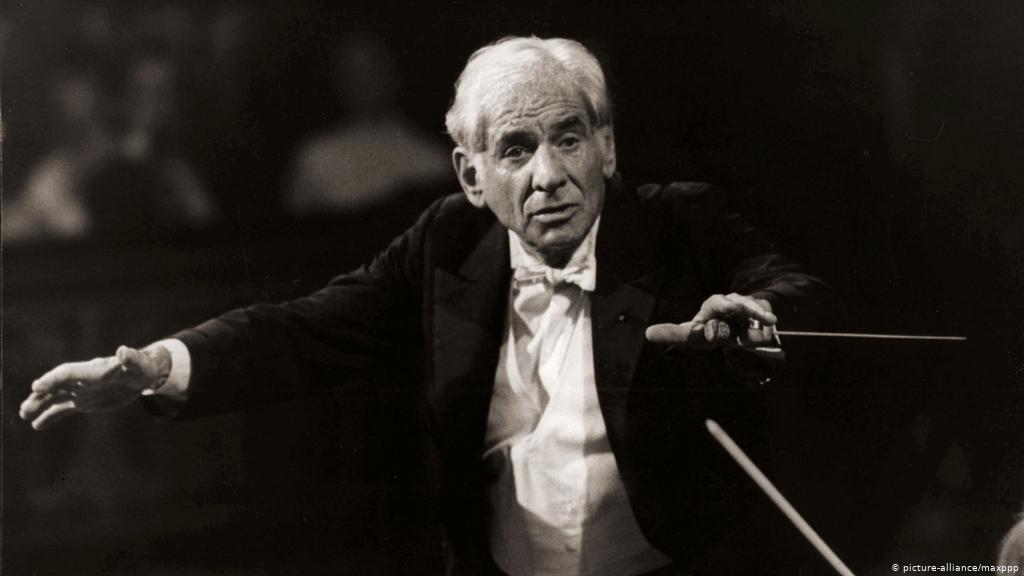

In her informed opinion, Mary is convinced “that of all Lenny’s talents, teaching was by far his favorite and probably his best. His conducting garnered him huge attention but not always unanimous admiration (he wriggled around like a puppy on the podium). For his composing, I’d put him in the top drawer for his early theater music from On the Town through West Side Story and I loved his early concert works, especially The Age of Anxiety.”

She sympathizes with how difficult it must have been for his wife, Chilean actress Felicia Montealegre, “a tiny, tinkly, delicate blonde who made every other woman in the room feel like a Clydesdale,” to be married to a gay male who wasn’t all that discreet.” Mary (who endured similar trials with her first husband) reports that it was well known Lenny had affairs with Aaron Copland, Dimitri Mitropoulos, and Tommy Cothran, the lover for whom he left Felicia two years before her 1977 death of lung cancer (they all smoked incessantly and drank heavily).

But Mary allows that “Lenny’s hugeness of spirit, however much collateral damage it caused, made you forgive almost everything else.” She concludes, “At least there was love between them, and their kids (Jamie, Alexander, and Nina) all ended up terrific.”

In later years, Mary believes composing grew more of a chore for Lenny who forced himself to write for his reputation. She recalls his arrival at one house party “sweeping in beyond-the-pale-late, wearing Serge Koussevitzky’s cape.” On the way home (he and Mary were being limo-ed by a wealthy friend to their separate digs), he thoroughly trashed Sondheim’s newly debuted “Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.”

As they arrived at the Dakota apartment building, his destination, he stuck out his lower lip and said, “You’re mad at me, aren’t you?” “Yes,” seethed Mary believing Steve’s unlabored flow of music had made Lenny envious. She concludes sadly, “Maybe it was the one thing he couldn’t do as well anymore. But my God, when he could!”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m reminded of the days when network television (and public television) took seriously the arts and would broadcast live performances. You would think that with all the attention being paid to expanding audiences beyond the connoisseurs there would be a clamor for such television, even locally. Only KING-FM seems to take this obligation seriously.