I had just turned the final page of Father and Son, Jonathan Raban’s dual memoir, when I unaccountably wanted to read it again. The book is that compelling, taking the reader beyond the author’s traumatic recovery story and into his father’s experiences in World War II. The two journeys are interwoven into 300 pages.

The book opens with Raban’s stark words: “I was transformed into an old man quite suddenly on June 11, 2011, three days short of my 69th birthday.” Sitting down to dinner with his daughter Julia, Raban had found himself unexpectedly asymmetrical. His left side was normal but his right arm and leg were weak. He reluctantly allowed Julia to drive him (while smoking yet another cigar) to an Edmonds hospital. There a doctor confirmed that he had experienced a hemorrhagic stroke paralyzing the right side of his body.

Raban owns up to having been “stupid” about his health, citing his heavy smoking habit and untreated high blood pressure. He ruefully notes that his vintage address book, held together with rubber bands, was filled with addresses of friends, smokers who had passed on.

Into his wry, sometimes comic and sardonic story of his pathway towards post-stroke recovery, Raban laces his parent’s tender wartime love story. On the one hand, the author provides unblushing accounts of struggling with the limitations of his new body. (He bristles at being infantilized and asked, “Do you have to go potty?”) In alternate chapters, Raban quotes liberally from Monica’s and Peter’s tender love letters.

Relying in part on contemporary accounts, the author follows his father fighting in France and Belgium, his rescue from Dunkirk, battles in North Africa and on the beaches of Anzio, concluding with skirmishes in Palestine. Through three long years, his newlywed parents exchanged hundreds of letters, millions of words, they made love, discussed income taxes, painted, wallpapered and furnished their home.

Monica, who had once earned small sums writing romantic fiction, tried to make the best of her wartime aloneness. She managed to buy a house at auction, put up with her meddling mother and tend to baby Jonathan. She describes him as a rambunctious child who suffered from an ailment likely misdiagnosed as celiac disease. Whatever it was, the malady left him underdeveloped and suffering bouts of nausea.

Born Jonathan Mark Hamilton Priaulx Raban (a jumble of forebearers’ names) in Norfolk, England, the author was later raised in his father’s vicarage and attended a penitentiary-like boarding school before graduating the University of Hull. He taught literature in Wales and East Anglia. He wrote fiction and radio plays for the BBC and criticism for London magazines and the New York Review of Books. There followed more than a dozen nonfiction works including Passage to Juneau, Bad Land, Hunting Mister Heartbreak and his novels Waxwing and Surveillance.

By the time of his stroke, Jonathan Raban had moved to Seattle. He’d been drawn here in 1990 partly by interest in dance critic Jean Lenihan (whom he’d marry and subsequently divorce) and by the lure of the city itself. In later years, the peripatetic Raban says, “Wherever I was, I felt like an outsider, a clumsy rube with skinny arms and a funny accent.”

I bumped into Raban several times during his early years here, including one night at Ponti’s Seafood Grill. We were among journalists celebrating some milestone — possibly retirement — in the life of Fendell Yerxa, one of my UW professors. Yerxa, a former New York Times bureau chief, had his regular barstool (far right-hand end) at Ponti’s bar. Raban, ever the superb raconteur, recalled Yerxa saying that a certain faculty meeting “was like a bunch of seagulls fighting over a pile of manure.”

During his five weeks in rehab at Swedish-Providence, Raban chafed at his sometime condescending caregivers while revering the good ones. He had warm words for puckish nurse Richard and physical therapist Kelli, although it was she who challenged him four times a day as he struggled to stand and do “transfers” from wheelchair to bed and toilet. When abed, he came to prize his light-weight Kindle. The device enabled him to read other writers’ stroke accounts and find solace in books like Tony Judt’s ”Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945.” He valued the lengthy account by Judt, a fellow British expatriate who died at 62 of Lou Gehrig’s disease.

That book reawakened in Raban the travel writer and salt-water sailor that he once had been. As he observed, “Strangeness is always a source of pleasure.” Never one for emotion, he’d find himself unwittingly breaking into tears, downright blubbering at times.

Raban relates how his daughter Julia printed blow-up photos of a road trip the two had taken just prior to his stroke, a trip featured in the New York Times magazine. Julia, who visited daily, tacked those evocative prints to his hospital room walls. He delighted in her visits when she recounted the day’s encounters at her summer job, soliciting door-to-door to extend Mount Rainier Park.

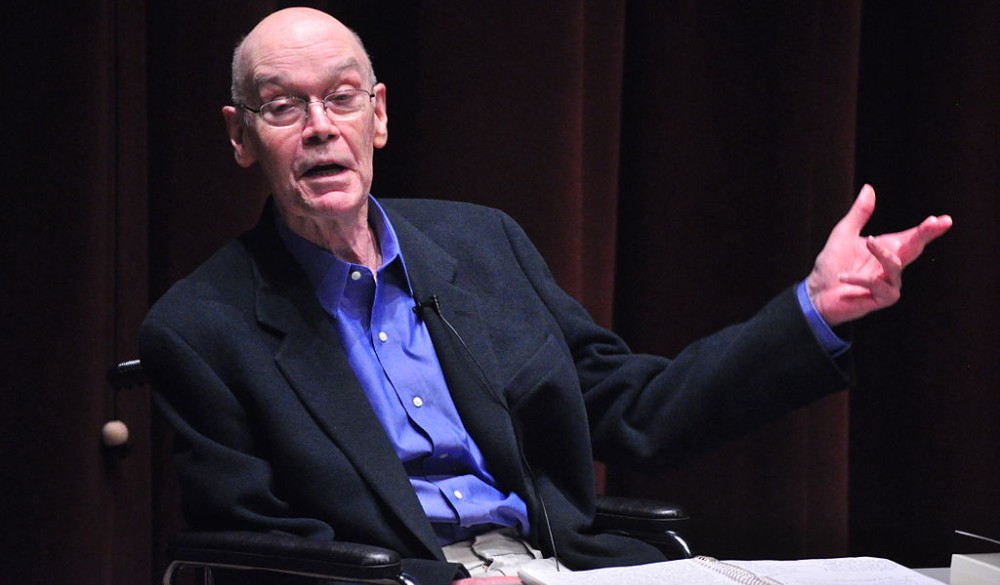

After five weeks in rehab, Raban returned, at first not to his Queen Anne home with its many steps, but to a single level cottage loaned by a generous friend. The author would eventually return to his hilltop home although he never regained the use of his right leg or hand. Left with only one hand he was unable to use his computer to write. But he still thought of himself as a writer. When a rehab doctor had dismissively referred to him as “someone who used to be a writer,” he insisted he still was a writer. Indeed he was. Despite his handicaps, slowly and painfully, he resorted to voice-activated software to complete Father and Son.

Some reviewers of the book have faulted Raban for failing to document his relationship with his dad on Peter’s return from war. However, the author does provide clues to that relationship. He mentions his father’s chilly tone in letters sent to him while away at boarding school. He reports on Peter’s belief in strict discipline for children. As an Anglican pastor, his pastoral letters were, according to Jonathan, “a trial to read, impregnably knotty,” far different from his father’s wartime letters with their emotional eloquence.

For my part, I found Raban’s book a heroic achievement. The book’s draft was finished during Jonathan’s final year and published posthumously last September. He died last January at 80 before doing the final copy edits. However, John Freeman, his editor at Knopf, found Jonathan’s work “balance perfect.” He called the book “one of the most miraculous feats” he’d ever witnessed. It tells an unforgettable story of two men, both intent on finding their way home.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks, Jean. Added that to my “must read” list.

Great job on the Raban book, Jean.

I loved it! I wish I could have gotten to know him, as I used to see him on Queen Anne a good deal during our days at the P-I.

Thanks for this. Years ago I occasionally crossed paths with Raban at the old Queen Anne Thriftway, but never had the nerve to introduce myself as a fan boy. “Father and Son” is excellent. Also worthwhile is “Driving Home: An American Journey,” a collection of his essays and articles.

Thank you Jean. It’s in my list now. I treasure the letters I have between Jonathan and Murray, especially one where he describes how besotted he is with baby Julia.

Just reread “Juneau” and was missing that voice. Looking forward to this one. Thank you.

I appreciate this article so much, Ms. Godden. It made me dig back into the New York Review of Books for his reviews of, e.g., Wallace and Gaddis. And in a roundabout way, it looks like I need to read Judt’s Postwar.

Before you open “Father and Son” and beginning reading again, I suggest you get the audiobook from the library and listen to his words spoken by a very able reader. I never had the chance to meet Rabat so I don’t know his voice. But this reader sounds so authentic that I feel like it is Jonathan himself talking to me. Needless to say I found it delightful and just as compelling as you describe it.

You’ve convinced me to get my hands on that book. The father/son journey resonates for me. The father I never knew and the replacement father who stepped in amid wartime. Loved Ponti’s. There was a regular Friday gagle of journos taking over a table or two in the bar. Hoisted a few with dear old Fendell now and then.

Just finished the book, Jean, and — I’m sorry — I found it unsatisfying. Not to denigrate the work Raban put into this, but I kept waiting for him to somehow integrate the story of his stroke and recovery with that of his father’s experience in WW II. Still waiting.

Sorry you were disappointing after reading Raban’s book. It’s true he didn’t fully flesh out his relationship his father, but that may have been understandable given his close relationship during wartime with his mom. When he and his mom faced one another across Peter’s deathbed said so much. Perhaps that was most telling.