Nov. 22 was the 60th anniversary of the assassination of the 35th American president, John F. Kennedy, a “cruel and shocking act of violence,” as the Warren Commission called it, “directed against a man, a family, a nation, and against all mankind.”

Montana Sen. Mike Mansfield, a close friend of the murdered president – they came to the Senate together in 1952, sat next to each other on the Senate floor and grew even closer during Kennedy’s presidency – played a central role as the nation and the world mourned the young president’s death. Mansfield’s tender handling of Kennedy’s memorial service illustrates the Montanan’s unique approach to leadership, as well as his capacity for decency and empathy, characteristics that remain his legacy decades after he left the Senate.

The Senate Majority Leader had chosen a Friday afternoon in November of 1963 to deliver a speech on political leadership, an effort after weeks of silence to respond to critics who charged that Mansfield’s low-key, inclusive, bipartisan approach just wasn’t tough enough or demanding enough to be successful.

Mike Mansfield, a soft-spoken former college professor who had once worked in the copper mines of Butte, Montana, had come to Senate leadership in 1961, replacing an aggressive, demanding, even overbearing predecessor, Texan Lyndon Johnson, now the vice president. The contrast in style was jarring and entirely new to the Senate, with one staffer remarking that the change from LBJ to Mansfield was “like going home to mother after a weekend with a chorus girl.”

Connecticut Senator Thomas Dodd was one Democrat who harshly condemned Mansfield’s style as flabby and ineffective. “I wish our leader would behave like a leader and lead the Senate as it should be led,” Dodd thundered on one apparently alcohol-fueled occasion.

“When Tom Dodd gave that speech in 1963,” Mansfield aide Charles Ferris recalled, “he was really pining for Lyndon Johnson. Some people thought the legislative process should be worked out behind the scenes rather than in an open forum.”

But working in the shadows, cutting deals in the Senate cloakroom, or trading favors over a glass of bourbon was simply antithetical to Mansfield’s notion of leadership.

With his different style of leadership Mansfield was attempting to create a different kind of Senate. But as another aide, Francis Valeo, described it, Mansfield’s approach could “only work if senators were prepared to accept a full share of personal responsibility for what went on and for the image that the Senate projected to the nation. Above all, it required that the Senate’s easily abused rules and indulgent practices be used with a maximum of self-imposed individual restraint and mutual consideration. Otherwise, rules intended to facilitate wise decisions became deadly impediments to rational legislative action and covers for inaction and inequity.”

But there would be no Mansfield speech on leadership on the dreadful Friday afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963, but subsequent events, both tragic and historic, would confirm the wisdom of the Mansfield way and create a string of legislative successes that still stand as among the most significant in American history.

United Press International posted the first bulletin at 1:34 p.m. eastern time: “Three shots fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade today in downtown Dallas.” The Senate chamber was nearly empty, but as word spread, senators came to the floor and clustered around the majority leader’s desk. Minutes earlier, after a whispered conversation with a reporter, Mansfield had muttered, “This is horrible. I can’t find words.”

Minutes ticked by and uncertainty grew. At 2:16 p.m. eastern time, Mansfield, surely knowing that the president and Texas governor John Connally had both been shot, took the floor and spoke of “a tragic situation” now confronting “the Nation and the free world.” Referring to Kennedy, Mansfield said that extreme danger “confronts a good, a decent, and a kindly man.” He and Republican leader Everett Dirksen of Illinois agreed, Mansfield said, that it would be appropriate for the Senate chaplain to offer a prayer “in the devout hope that he, the Governor of Texas, and others will recover.”

After learning from wire service bulletins that Kennedy had died, for the only time anyone could remember, Mansfield said to an aide, “Get me a drink.” He then retreated, alone, to his office, where he remained for 30 minutes. “Mansfield was very stoic,” Charles Ferris remembered. “He kept his emotions very contained.”

But the majority leader who had come to the Senate with Kennedy and developed a deep affection for a fellow Irish Catholic, was shaken profoundly. “Jack Kennedy, I think, was like a son to him,” Ferris said.

Mansfield, his wife, and daughter met Air Force One at Andrews Air Force base late that Friday night when it returned from Dallas carrying Kennedy’s body, his widow, and the strapping Texan who was now president.

Sometime during the next chaotic hours, Jacqueline Kennedy personally phoned Mansfield requesting that he alone deliver a eulogy during the memorial service planned for the rotunda of the Capitol on Sunday, Nov. 24. Mansfield agreed, but it was later determined that protocol required that someone from the House of Representatives also speak. Ultimately, Speaker John McCormack and Chief Justice Earl Warren also delivered remarks in the echoing space below the Capitol dome. Sixty years later only Mansfield’s words are remembered.

Mansfield worked on his Kennedy eulogy in the post-midnight despair of Saturday, Nov. 23. Francis Valeo, who wrote many of Mansfield’s speeches, claimed a hand in the drafting, and apparently Rhode Island Sen. John Pastore reviewed a draft. The drafting may have been a collective effort, and it likely was, but the inspiration for Mansfield’s remarks, delivered next to the president’s casket in the Capitol, was his alone.

“The words uttered by Senate Democratic Majority Leader Mike Mansfield Sunday in his eulogy for President Kennedy are echoing through the country,” the Boston Globe reported. “They were inspired by a poignant gesture by Mrs. Kennedy Friday.”

On the day of the murder, Mansfield apparently heard a broadcast news account of Jacqueline Kennedy placing a kiss on the lips of her dead husband and slipping her own wedding ring into his hand. That gesture became the connective theme of Mansfield’s haunting 400-word eulogy, more a prose poem than a speech. The words still shock with their power and their profound sense of tragedy.

“There was a sound of laughter and in a moment, it was no more,” Mansfield said in a precise, measured cadence. “And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands.

“There was a wit in a man neither young nor old, but a wit full of an old man’s wisdom and a child’s wisdom, and then, in a moment it was no more. And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands.

“There was a man marked with the scars of his love of country, a body active with the surge of a life far from spent and, in a moment, it was no more. And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands.

“There was a father with a little boy and a little girl, and a joy of each in the other, and in a moment it was no more. And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands.

“There was a husband who asked much and gave much, and out of the giving and the asking wove with a woman what could not be broken in life, and in a moment it was no more. And so she took a ring from her finger and placed it in his hands, and kissed him, and closed the lid of the coffin.

“A piece of each of us died at that moment. Yet, in death he gave of himself to us. He gave us of a good heart from which the laughter came. He gave us of a profound wit, from which a great leadership emerged. He gave us of a kindness and a strength fused into the human courage to seek peace without fear. He gave us of his love that we, too, in turn, might give. He gave that we might give of ourselves, that we might give to one another until there would be no room, no room at all, for the bigotry, the hatred, the prejudice, and the arrogance which converged in that moment of horror to strike him down.

“In leaving us these gifts, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, President of the United States, leaves with us. Will we take them, Mr. President? Will we have, now, the sense and the responsibility and the courage to take them? I pray to God that we shall and under God we will.”

“I shall never forget Mike Mansfield’s speech,” Lady Bird Johnson wrote in her diary, “he, the most precise and restrained of men – repeated over and over the phrase ‘and she took a ring from her finger and placed it on his hand.’”

Albert Steinberg, a Lyndon Johnson biographer, believed that “Mansfield, in his loud, crisp voice with the Irish lilt” had “delivered a magnificent eulogy.” And William Manchester, who interviewed the former first lady for his book The Death of a President, later wrote: “Only Jacqueline Kennedy could judge Mike Mansfield, and she couldn’t believe what she was hearing; she didn’t know a eulogy could be this magnificent; looking up into his suffering eyes and his gaunt mountain man’s face, she thought his profile was like a sixteenth-century El Greco. To her the speech itself was as eloquent as a Pericles oration, or Lincoln’s letter to the mother who had lost five sons in battle. It didn’t turn aside from the ghastly reality – ‘It was,’ she thought, ‘the one thing that said what had happened.’”

With his words still echoing beneath the Capitol dome, Mansfield walked the short distance to where Mrs. Kennedy was standing and handed her his copy of the eulogy.

“You anticipate me,” she said. “How did you know I wanted it?”

Mansfield ducked his head slightly – bowed some said – and responded, “I just wanted you to have it.”

In the vast Mansfield archive in the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library at the University of Montana, no correspondence is more poignant or more personal than the letters Jackie Kennedy wrote the majority leader after the death of her husband. Maureen and Mike Mansfield called on Mrs. Kennedy a few days after the president’s funeral and before Jackie had moved from the White House. She responded to their thoughtfulness with a handwritten note: “I do thank you and Maureen for coming to see me. The only time things are better is when I talk about Jack – and you and he were so close and built so much together. I will always care terribly about your happiness. Love, Jackie.”

Ten years after the Kennedy assassination, the nation paused, as we will this year, to remember the awful day in Dallas.

Jackie Kennedy was watching an evening news program with her son when Mansfield’s eulogy was rebroadcast. She commemorated the occasion with another handwritten note to Mansfield: “Other people will remember Jack all this weekend – but yours was different – because you are different. There is no one on this earth like you. Thank you dear Mike, with all my heart. Please forgive the incoherence of this letter. It is written with much emotion—and all my love – Jackie.”

After John Kennedy’s murder, complaints about Mansfield’s unique, inclusive and bipartisan approach to leadership faded nearly entirely away, replaced during the decade of the 1960s by a sense of historic accomplishment. Often working in complete cooperation with Republican leader Dirksen, the legislative record includes passage of civil rights and voting rights legislation, approval of the Wilderness Act, creation of fair housing legislation, Medicare, public broadcasting, support for education, creation the national endowments of the arts and humanities and much more.

Mansfield’s treatise on leadership, merely entered into the Congressional Record in 1963, faded away as well, abandoned amid the shock of Dallas. Only in 1995, thanks to an invitation from then-Senate leader Trent Lott of Mississippi, was Mansfield, long retired and in his 95th year and the longest serving majority leader, able to deliver the speech he had planned 35 years earlier, on the day John Kennedy died in Dallas.

Mansfield was in rare form presenting what amounted to a lecture on leadership, a speech that Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, a keen student of political history, hailed as one of the greatest in Senate history.

Speaking in the old Senate chamber of the Capitol in direct, colorful language Mansfield laid out his approach.

“Of late, Mr. President, the descriptions of the majority leader, of the Senator from Montana, have ranged from a benign Mr. Chips, to glamourless, to tragic mistake.

“It is true, Mr. President, that I have taught school, although I cannot claim either the tenderness, the understanding, or the perception of Mr. Chips for his charges. I confess freely to a lack of glamour. As for being a tragic mistake, if that means, Mr. President, that I am neither a circus ringmaster, the master of ceremonies of a Senate night club, a tamer of Senate lions, or a wheeler and dealer, then I must accept, too, that title. Indeed, I must accept it if I am expected as majority leader to be anything other than myself – a Senator from Montana who has had the good fortune to be trusted by his people for over two decades and done the best he knows how to represent them, and to do what he believes to be right for the nation.”

Mansfield continued with a detailed description of what the United States Senate can be, and often for a time under his leadership became.

“Within this body, I believe that every member ought to be equal in fact, no less than in theory, that they have a primary responsibility to the people whom they represent to face the legislative issues of the nation. And to the extent that the Senate may be inadequate in this connection, the remedy lies not in the seeking of shortcuts, not in the cracking of nonexistent whips, not in wheeling and dealing, but in an honest facing of the situation and a resolution of it by the Senate itself, by accommodation, by respect for one another, by mutual restraint and, as necessary, adjustments in the procedures of this body.

“The constitutional authority and responsibility does not lie with the leadership. It lies with all of us individually, collectively, and equally. And in the last analysis, deviations from that principle must in the end act to the detriment of the institution. And, in the end, that principle cannot be made to prevail by rules. It can prevail only if there is a high degree of accommodation, mutual restraint, and a measure of courage–in spite of our weaknesses–in all of us. It can prevail only if we recognize that, in the end, it is not the Senators as individuals who are of fundamental importance. In the end, it is the institution of the Senate. It is the Senate itself as one of the foundations of the Constitution. It is the Senate as one of the rocks of the Republic.”

Sixty years have passed since John Kennedy’s death in Dallas, and it is entirely appropriate to reflect on what America has seen and become in those six decades. And amid the memories and the mysteries of what might have been, it is also appropriate to understand that the political dysfunction that grips our country, the hyper-partisan division, the disdain for basic decency and the rejection of long-established political norms is merely a choice made by some people in public life. Politics doesn’t have to be the way it has too often become. Mike Mansfield proved that.

Mansfield’s legacy reminds us that civility, responsibility, genuine respect for political opponents and a commitment to self-restraint and fair play are and must be fundamental to a functioning democracy.

As Mansfield said in 1995, our nation “belongs … not to one of us, or to one generation, but to all of us and to all generations.” We must strive to keep that nation by supporting and raising up democracy, respecting the Constitution, embracing ethical and responsible leaders and celebrating the essential decency of politicians like Mike Mansfield.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for sharing this beautifully written piece of history.

Marc, thank you. Words can’t express my excitement in reading this extraordinary piece of journalist history.

Yes, thank you and I will read the book.

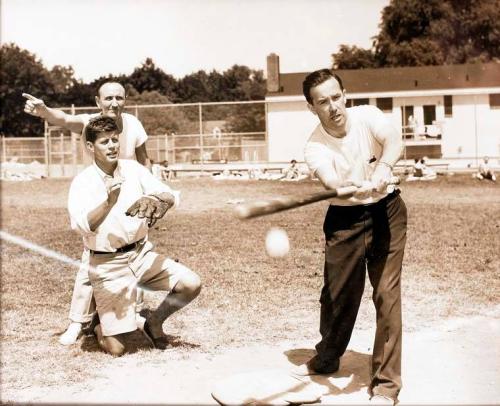

And the photo of Mansfield, Scoop, and John Kennedy also hung in Scoop’s Office.

By the way, he said he “homered”:)