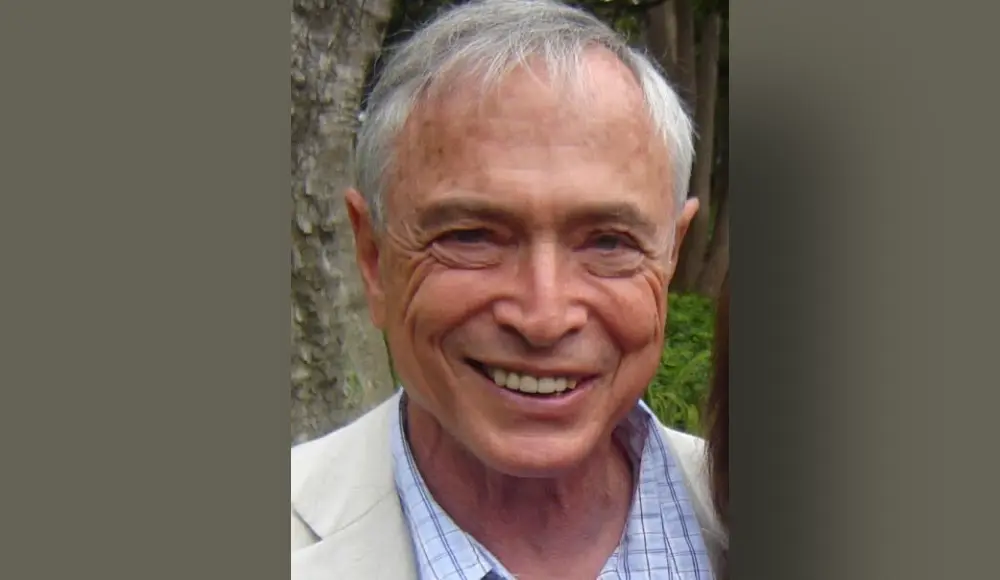

Dr. Abe Bergman of Seattle, who died November 10 at age 91, liked to say that politicians could save more lives than doctors. Throughout his long career he proved that statement true, at least if the politicians were inspired – and ceaselessly pushed and cajoled – by Abe.

Most famously, working through his lifelong friend Jerry Grinstein, now also 91, Abe consistently inspired Washington’s two most powerful former U.S. Senators, Warren G. Magnuson and Henry M. Jackson. That inspiration yielded a flood of federal laws that continue to save American lives.

Abe accomplished great things in Olympia too. All the while Abe continued doing what he loved most, namely treating patients, and particularly kids. He was the kindest, smartest, and most attentive pediatrician any parent or child could hope for. To top it off, he was a successful literary agent. (I’ll explain.)

Abe was only 37, and I was a 21-year-old legislative assistant, when he strode into Magnuson’s Senate office in early 1970, armed with an introduction to me from Grinstein, and confidently announced – highly improbably – that Magnuson, Jackson, Abe, and I were going to create something Abe called the National Health Service Corps. Ten months later, on New Year’s Eve and against all odds, President Nixon signed Magnuson’s and Jackson’s NHSC bill into law.

It was an extraordinary legislative coup, but only for that early stage in Abe’s “political medicine” career. By the end of his life, Abe considered the NHSC just one of his minor achievements. Yet 52 years later there are now 20,000 NHSC health professionals actively working in the field – doctors, nurses, dentists, audiologists, and others of every medical type – and more than 60,000 NHSC alumni. In the past half century, NHSC professionals have saved millions of American lives in hundreds of medically underserved rural areas, small towns, densely packed inner cities, and on Native American reservations across the land. A minor achievement indeed!

One can appreciate Abe’s perspective in not over-emphasizing the NHSC among his accomplishments. Consider just a fraction of his other federal achievements:

- The Flammable Fabrics Act, enacted in 1970, the same year as the NHSC. Children and adults burning to death or becoming hideously scarred because their nightclothes or other garments caught on fire sickened Abe – and angered him. He’d attended to too many needlessly burned kids at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital in Seattle, his professional home for decades. Characteristically, he didn’t just write or speak about the problem. He dragged Magnuson and Grinstein to the Children’s burn ward and made them look at the kids and talk with them. Magnuson went back to D.C. and got flammable fabrics banned within months.

- The Consumer Product Safety Commission. It’s difficult to believe now, but until the 1970s there was no agency responsible for assuring the safety of consumer products. Magnuson got that changed after Abe showed him and Grinstein (as well as another top Magnuson’s aide, the late Michael Pertschuk, who created his own Abe-inspired legacy when he became Chairman of the Federal Trade Commission) X-rays of a victim’s skull embedded with sharp metal objects thrown by an ordinary lawn mower. The images were horrifying, but effective.

- The Poison Prevention Packaging Act. Nowadays, as we sometimes struggle to open a bottle of medicine, it’s easy to forget that until Magnuson acted in response to Abe’s urging and Abe’s carefully assembled statistics, thousands of American kids died each year after simply turning the caps of such bottles and ingesting whatever pills or liquids they found inside. This was another Bergman-inspired law that’s saved a great many lives. (And yes, also at Abe’s urging, the law allows simpler closures for adults with arthritis or other conditions that make the safer containers difficult.)

Undoubtedly, Abe’s proudest Congressional accomplishment remains the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, which he drafted and helped create, working through Senator Jackson and Jackson’s aide Forrest Gerrard, a Native American who – along with Jackson – Abe came to adore. The abysmal state of health care for Native Americans, on and off the reservation, hardly needed to be proven, but it needed to be acted on. Abe threw himself into making it impossible for Congress to ignore. Jackson effectively added Abe to his staff for the legislative effort, just as Magnuson had for the NHSC and flammable fabrics, and a great new law resulted. Abe even wrote a vivid account of the bill’s Congressional saga.

Abe would be quick to complain that the tremendous promise of the Indian Health Care Improvement Act has yet to be completely fulfilled. Things are better, thanks to the law, but not as great as they should be. With Jackson gone these 40 years, Congress and the Administration seem to have lost some of their focus on this among other important laws. But although Native Americans still do not receive fully the health care they deserve, it was at least some solace to Abe that among the medical professionals who do serve on reservations, many do so under the auspices of the National Health Service Corps.

Before continuing this catalogue of Bergman-kickstarted laws, it’s worth pausing to explain the force of personality that enabled Abe to succeed where others with equally bright ideas might have failed. Abe could be a very nice person, a true charmer, as he always was with little kids especially. But patience was never his thing.

In particular, should any bill he cared about get hung up in committee or otherwise delayed before final passage, Abe could be a nag, a demanding pest, contemptuous of anyone else’s brief respite from work, and even downright rude. Anything less than constant, 100 percent effort by any relevant Congressional staffer invited a stream of phone calls, letters, and unannounced personal visits, not just at the office but even at one’s front door in the evening. When Abe had us in his sights, we staffers felt guilty to work on anything but his legislative causes – or even pausing to have dinner. But we did do better because of him.

Despite his hectoring, we all recognized that Abe’s compassion for those who suffer – psychically and emotionally, not just medically – was by far the dominant strand of his personality. For example, in the late 1960s, determined to discover the cause and cure for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), Abe and his colleagues at Children’s Hospital persuaded the Washington Legislature to enact a law requiring an autopsy at Children’s for any child under the age of two who died suddenly. But that was only half the effort.

The other half was a nationwide campaign, launched from Children’s, to end the cruel prosecutions of parents who’d lost a baby to SIDS. Prosecutions? Yes, hundreds per year, although it seems almost unbelievable today. As late as the 1970s, too many coroners and medical examiners still named parental neglect or criminal negligence as the cause of death for SIDS infants. Abe’s campaign identified the ill-informed coroners and prosecutors, beginning with the most influential ones in New York City and Los Angeles, whom Abe convinced to spread the enlightened word. Abe even testified, all across the nation, as a powerfully effective defense witness for traumatized parents at their trials.

Racial and other forms of discrimination in health care infuriated Abe too. And legislation wasn’t always required to deal with it. For example, Abe played a key role in getting the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic established in Seattle’s Central District, which at the time had a predominantly Black populace and very little accessible health care. And for the past 20 years, Abe’s great love has been Seattle PlayGarden, a special city park for children with disabilities, which Abe helped found in 2002 and for which he worked to secure the land and necessary funding.

From a list that could go on and on, two of Abe’s most obscure and humorous contributions deserve a final mention. When he was still in his thirties, Abe among others considered it ridiculous and harmful that, in Washington state, condoms could be sold only by licensed pharmacists. He reasoned that sudden passions rarely overcame young men and women, much less desperate teenagers, on visits to pharmacies. When Abe and his allies finally convinced the Legislature to allow the sale of condoms in restrooms, Abe hosted a Pioneer Square party at which, dangling like ornaments from a Christmas tree, inflated condoms of every color and texture festooned the branches of potted rubber trees.

And yes, Abe actually did serve as a successful literary agent. In 1972, two years after we’d worked together for Senator Magnuson on the NHSC bill, I finished a book, The Dance of Legislation, describing the bill’s suspenseful legislative odyssey. It’s largely a book about Abe himself, but that’s not why he believed it deserved a national audience. He thought it showed the importance of “political medicine.” So Abe shared the manuscript with a close friend and colleague on the Sudden Infant Death Foundation board of directors, who happened to be the cookbook editor at Simon & Schuster. She took it from there.

Having helped that book circumvent the publisher’s dreaded slush pile, Abe was surprised but delighted to begin receiving 15 percent of the royalties, particularly when the book ended up selling hundreds of thousands of copies. Later I teased him about needing every penny, considering that he never thought of money but ended up the father of eight children, his very own cluster of boys and girls, all of whom he loved intensely.

Love, intensity, and effectiveness. That was Abe Bergman. One can only hope that through the lives of the millions of Americans who’ll never know to thank him, all that love and intensity and effectiveness will long endure.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My God, I did not know that he had died. Although I never met him, I had great respect for Abe Bergman. His tireless championing for children’s health, for Native American rights for health care with dignity, for rethinking how we treat mental illness sufferers, but in particular, it seems, he was a voice for struggling people. Who knows how many lives he saved? I remember that he wrote movingly about a son who struggles with mental health. I’m sorry to hear this. We’ve lost a great one.

Dr. Bergman deserves a statue. Or many, at the places around our region that exist because of his tireless efforts. I was so fortunate to have met him on several wonderful occasions, and he is all the things that Mr. Redman (himself a legend and hero!) describe, and then some. Thank you for this beautiful tribute.

Thank you for writing this, and detailing Abe’s enormous achievements. He had a remarkable impact on Seattle, and on the country, and his passing merits a lot more attention than it has received.

I am embarrassed to admit it, but when Abe reached out to me a few months ago and said he was looking for some political advice and wanted to talk, I had no real idea who he was, other than that he was a fellow Reed College grad (we’d met briefly years ago at Reed donor event) and had been a successful and prominent local pediatrician prior to his retirement. We got on a Zoom call, and he expressed to me his deep personal frustration about our complete failure as a society to address untreated mental illness on the streets of Seattle. He told me the heartbreaking life story one of his close family members, suffering from serious mental illness, who is homeless and addicted on the streets of Seattle.

He then asked me, “why is it so hard politically to reform our involuntary commitment laws so we can actually get people like that the help they need?” and I recall him adding, “Sandeep, I’m 91 and in poor health, so I can’t really take this on myself. But our neglect of these people and their suffering is unconscionable. Isn’t there someone who will take this on, isn’t there some pathway to get this done?”

I was deeply moved by Abe’s clear-eyed compassion, but I didn’t have a great answer for him. I told him I too had tried to initiate a political conversation along the same lines a few years ago, but got nowhere. I did promise him I would try again, and was on the verge of setting up a follow up meeting when I learned of his passing.

So maybe it’s a pipe dream, but I guess I’m thinking now that it’d be a tremendous capstone to Abe’s incredible life of political good works if we, as a city and a state, could take up his (final) call to to develop more proactive interventions to get those suffering from serious mental illness on our streets the help and care that they need.

Thank you for this. As one of his kids, myself a pediatrician, with similar vantage of heartbreak and despair on this situation— yes please. All the outrage and action—- and/but I have also had the thought- wow, it says a lot about the difficulty of an issue when even my Dad can’t budge it.

No need for embarrassment Sandeep, our Dad wasn’t interested in personal publicity.

Right on, Sandeep.

It seems we regard involuntary commitment laws as sacrosanct and the lives of people with serious mental illnesses who are homeless, perhaps addicted to harmful substances, and mostly unable to care for themselves as unfortunate consequences of those laws. I think we have to do better because otherwise we are ‘letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.’ I have no doubts that addressing this situation will be extremely difficult, but I agree with the late Dr. Bergman, and many others, that it is unconscionable that the suffering of too many people persists.

Thank you for this piece! Impossible to capture him all indeed but this is my favorite tribute yet no doubt. Much appreciated.

Eric, thank you for a great remembrance. My mom worked with Abe back in the beginnings of the “injury research” project at Children’s Hospital. We spent time with his family in those days and also, in a small world, later had connections to your extended family.

I also greatly enjoyed reading “The Dance of Legislation” in junior high and loved having it assigned in my college political science class too (feeling rather smug that I had already read it). Terrific book and chronicles such an important time in the effort to protect kids.

Thanks!

I worked with your mom too, Kevin I really liked her a lot. So sad that she died so young. She was an absolutely wonderful person.

Thank you so much Ric and to the commentors as well. Another of Abe’s kids here.

In light of Dr. Bergman’s passing, everyone should re-read his last column published in Post Alley News. And then we can work on finding a legislator to sponsor legislation to do what he asked. We can call it “Abe’s Last Wish”.

https://www.postalley.org/2023/08/20/bring-back-asylums/

So fortunate to have met this wonderful man and work closely with his brother Elihu in DC. Then later on while working with Ric working with Mathew his son. THIS ERA was an amazing part of our history and i love that Ric captured the true essence of Abe Bergman and continues to remind us of how true democracy works.

What a wonderful recap of an amazing career. Coming to Seattle at the Regional Health Administrator for Region X USPHS I was lucky enough to meet and benefit from Dr Bergman’s guidance and support. He was wise without every losing his sense of humor. Eric, the Dance of Legislation was required reading Thank you for reminding us of Dr Bergman’s contributions.

Our Dad would hate all these tributes but pleased (with grumbles) at having his books available to everyone for free. https://archive.org/details/the-discovery-of-sudden-infant-death-syndrome/page/205/mode/2up

Rick – many thanks for your superb overview of Abe’s stunningly remarkable achievements. While in no way personally involved in any of his projects (excepting the smallest of roles in creating the PlayGarden) what comes through in spades is his modesty – although we were close friends, walking, talking, eating and being hectored on a weekly basis, I was unaware of some of his amazing achievements.