In the movie The Big Short, the story of the men who made a killing off the economic crash of 2008, the heroes were the outsiders of the investment world — the geeks in a garage and the fund manager who drowned out his critics by listening to heavy metal. Zeke Faux’s new book, Number Go Up Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall, (Currency, 2023, $28.99), is about a more recent crash, the cryptocurrency panic of 2022. In his book, the zanies are not heroes and their thinking is not right.

Faux is a journalist at Businessweek. He starts his book as a reporter on assignment to look into one of the crypto companies, Tether. In the pursuit of his story, he goes to a convention in Miami called Bitcoin 2021. “Number go up” is a goofy phrase from one of the speakers, who has the rah-rah belief that crypto will never come down.

Faux also has a bias. “From the beginning,” he writes, “I thought that crypto was pretty dumb.” For years, this reviewer was also a business journalist, and I looked at crypto the way Faux does — that crypto is not a real currency, as its creators claim, but a kind virtual play-money, like points in a video game, and that it was crazy to pay actual dollars for it in a worldwide bidding war.

The story Faux tells is like a building full of odd nooks. One of them involves video games. Two decades ago, Brock Pierce, one of the industry’s founding fathers, had immersed himself in an online video game called EverQuest, which was a kind of Dungeons & Dragons. The player who advanced in the game won swords, shields, gold, and other stuff.

The game allowed players to trade this stuff inside the game. Then players began trading their virtual assets outside the game, for real money. In 2001, Pierce started a brokerage for these trades, International Gaming Entertainment. IGE became a multimillion-dollar company trading virtual goods in MMORPGs — massively multiplayer online role-playing games — such as World of Warcraft.

From the idea of virtual assets for real money it’s only a short jump to the idea of virtual assets as real money.

Video games are a nook or backstory, of which there are several in this book, which is mainly a reporter’s book. Faux starts with attending the Bitcoin convention, with its rah-rah speakers. He shadows the Italian who controls Tether. Faux dips his hand into the market for digitized ape cartoons, which the cognoscenti honored with the name “non-fungible tokens,” or NFTs. Faux visits El Salvador, the only country that adopted Bitcoin (sort of) as its national currency. He visits the Philippines, which was convulsed in 2021 by a craze for the video game Axie Infinity, in which players could earn crypto tokens called Smooth Love Potions, which they could sell for Philippine pesos. He talks to the Filipino who started the craze and rode it to the end. On a darker nook, Faux takes a taxi ride to a city in Cambodia run by gangsters, where captives are made to run internet scams in which the victims pay in crypto.

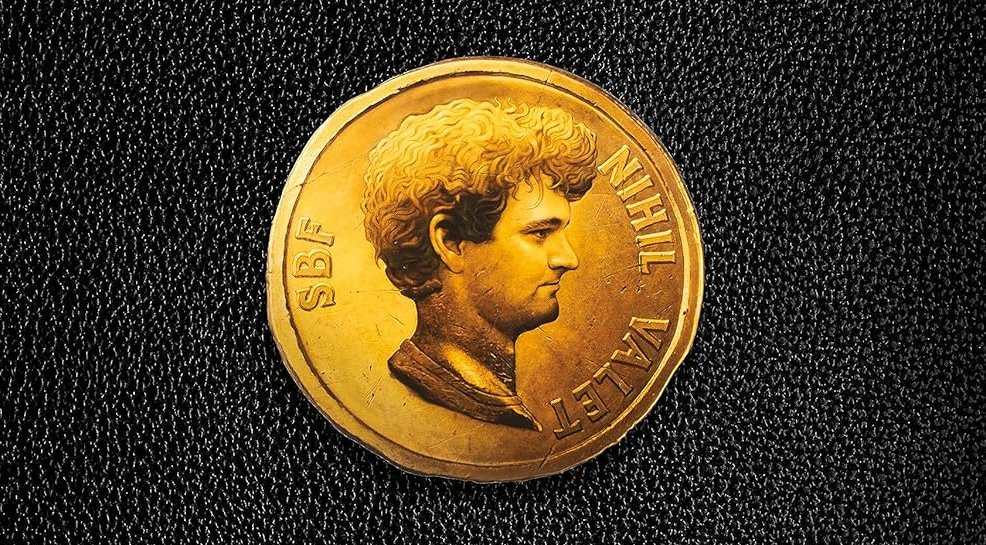

Faux also tracks down key people, including Sam Bankman-Fried, the mop-haired crypto king now facing trial in federal court. After his first private interview, Faux writes, “The billionaire shuffled in, shoeless, wearing white crew socks, blue crew shorts and a gray FTX T-shirt. He grabbed a pack of microwavable chickpea korma, ripped it open and started spooning it into his mouth, cold.” Bankman-Fried’s assistant introduced Faux as a journalist. “Oh, hey,” Bankman-Fried said. Bankman-Fried tells him, “I’m not going to lie.” And Faux writes, “This was a lie.”

Another of the odd nooks in the story is the idea of “effective altruism.” The idea is a sort of global utilitarianism — the greatest good for the greatest number — which in Bankman-Fried’s interpretation became a carte blanche to pile up money as long as he intended to eventually gave it away. “Bankman-Fried spoke like he really could save the world,” Faux writes. “But it seemed like his philosophy would justify doing almost anything to make money.” He didn’t get around to much giving to the poor, but in 2020 he did give $5 million to a committee supporting Joe Biden for president. In the 2022 midterms, he and other FTX officers donated $90 million to various campaigns.

Number Go Up also parades the credulous celebrities who latched on to crypto and to Bankman-Fried when he was riding high: Matt Damon, who did a TV ad for crypto.com; Paris Hilton, who showed off her digitized ape cartoon on The Tonight Show; and New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who once joked to Bankman-Fried, “I’m offended you have a much more glorious Afro than I once had.”

Faux’s book is not the only one on this topic. Michael Lewis, who wrote The Big Short more than a decade ago, has Going Infinite, a new book about the rise and fall of Sam Bankman-Fried. In Number Go Up, Faux describes Lewis on stage at a crypto conference, lavishing praise to Bankman-Fried: “Three years ago, nobody knew who you were,” Lewis says. “And now you’re sitting on the cover of magazines. You’re a gazillionaire.” Faux remarks, “Lewis said he knew next to nothing about cryptocurrency. But he seemed quite confident that it was great.” It’s a not-too-subtle put-down of a rival whose book is nonetheless on the bestseller charts, selling better than Faux’s.

Faux does know something about cryptocurrency: that most crypto “coins” are “transparently useless” except as vehicles for speculation. The exceptions are the “stablecoins,” which are tied to a real currency. In Faux’s view, their main value is in making international currency movements harder to track — a feature of particular value to criminals. He focuses on Tether, a stablecoin company that has weathered the crypto storm with the value of its unit intact. Faux pokes at the edges of Tether and shadows its boss, Giancardo Devasini, but at the end of the book the company remains a mystery.

Number Go Up raises the issue of government regulation. I can imagine people, progressives especially, declaring that the whole thing is an example of what happens when government leaves big-money finance unregulated, which happened under Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and so on. And that’s not quite right. The financial industry is regulated in lots of ways and has been for a long time. Crypto was started by people outside the financial industry, which wanted nothing to do with it. Crypto was different.

One example is in how crypto companies raised capital. In an ordinary initial public offering (IPO) of stock in the United States, a company has to disclose its assets and liabilities, how much stock the insiders own and how much they paid for it, how much the public is getting for what it’s being asked to pay, and so on. The would-be investor is given a boring-but-useful booklet of information called the prospectus or “red herring.” The crypto companies didn’t provide any of those. They weren’t selling stock; they were selling “coins” — virtual coins, visible only in the netherworld. Faux argues that the law should have been applied to those, but it wasn’t.

Other laws apply to companies with operations in the United States. Not coincidentally, a lot of crypto operations have been based offshore. Bankman-Fried’s FTX exchange was in the Bahamas. His trading company, Alameda Research, was in Hong Kong. Binance, the largest surviving crypto exchange, is based in Malta, as far as I can tell. Call up its main web page, Binance.com, and a pop-up says, “Binance.com is unavailable in your country or region. If you are in the United States or select U.S. territories, Binance.US is a U.S. registered platform where you can buy, trade, convert and stake crypto with low fees.”

I go to the U.S. web page and see “BTC $28,234.09.” That’s Bitcoin. With your U.S. dollars, you can buy it, as well as Ethereum, Dogecoin, Solana, and several others. The game is still on.

Regarding Faux’s book, the thought comes to mind that we are a country in which a lot of people have a lot of money, and they will use it the way they want. Caveat emptor.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you Bruce for this good book review. I was always sort of suspicious of even the idea of bitcoin myself, and I think that you and this book have proved my suspicions true. It’s a virtual thing I guess. Maybe my kids would understand it, but I don’t.

The cloud now uses the same amount of energy in electricity as the whole nation of Japan. This is a big chunk of the total global consumption of energy for the world of computer virtual existence.

If our idea of real money, or rather a summation of what we’ve earned, and what we’ve put in the bank, and what we rely on for retirement, now becomes a virtual video game type of thing, then my gosh it seems that we’ve suddenly lost it all to something that really can’t take us into the future.