Harvard-educated, raised in a Philadelphia family of means and influence, friend of Theodore Roosevelt, an attorney and composer — Owen Wister did not easily fit the mold of a western cowpoke. He did the next best thing by writing The Virginian, the model for a flood-tide of Old West literature to follow. His famous words from that broad-shouldered page-turner: “When you call me that, smile.”

Wister, between engagements as a writer, ranch hand, colorful presence at eastern social engagements, and family man, spent time roaming the West, including parts of our State of Washington. In 1887, fresh from Harvard Law School, Wister asked his father for money so that he might “go West and ride through the Big Horn Mountains and the Yellowstone (Montana).” His father came through, allowing young Wister to begin his maiden journey to our Far Corner. He followed the Snake River (200 miles shorter than the mighty Columbia), touching Washington briefly, then returned east via Chicago and a comfortable bed in the famed Palmer House.

In 1888-89, Wister returned West, mostly exploring the Wyoming wilderness, especially the historic and beautiful Jackson Hole fur trade center. In October of 1892, Wister visited Harvard classmate George Waring, who kept a small general store on the Methow River. He stopped in Walla Walla, then Washington Territory’s largest city, which he described as “a town of dust and poplars.” He also observed that the “Palouse Indians” are “much civilized, the squaws virtuous, and the men pay their debts.” These attributes, Wister was told, were due to the influence of the “Church of Rome.”

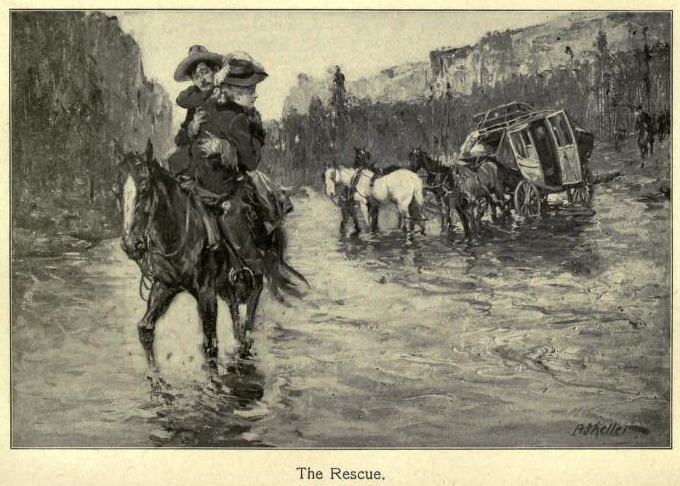

He travelled by stage between Walla Walla and Spokane, again moving along the Snake River’s shores, noting at some points that the river was “quite large,” allowing steamboats to run between the “vast bare hills.” Wister continued to Coulee City, later the site of one of the world’s largest dams, and explored the area. At the Hotel Grand he was given a room “about the size of a spittoon,” although he washed in the “public trough” between the saloon and the dining room. He added to his western knowledge by watching a poker game in the saloon, and the next morning found the game still underway. That “ceaseless” game was a “cheap one, and nobody got either drunk or dangerous.”

After boarding his stage, he proceeded to Bridgeport where he got an eyeful of the Columbia River, which he described as “restless rapid river with a rapid current, flowing among dismal hills.” A Jewish peddler accompanied Wister on most of this leg. Finally connecting with his friend George Waring, Wister drove through Waring’s gate where he saw a flag flying with a boar’s head on a white field — the emblem of Harvard’s Porcellian Club.

In late November 1892, Owen Wister started home, leaving what he called the “Big Bend” country. He returned to family obligations and his library. The Porcellian Club flag no longer flies in the Valley, but The Virginian thrives as the backbone of American Western literature good and bad.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“Smile when you call me that” thems fightin words!

I should look it up, but i remember reading The Negro Cowboy some years ago, and reading that Wister, a Manifest Destiny believer with a background in southern racism, “erased” Blacks from the West. At the time, in the late 1800s, there were many Black cowboys and cattlemen, but none appear in Wister. I’ll try to find that old book and check on it, but i don’t remember any African-Americans in The Virginian.

Readers seeking a different, well-written, and well-researched account of Owen Wister and his views of the American “West ”must read Stanford Historian (and former U.W. Professor) Richard White’s much-respected “It’s Your Misfortune and None of My Own – a New History of the American West”, published by the highly regarded University of Oklahoma Press in 1994.

White explains that the popularity of Wister’s 1902 tale “… depended on the mass media, and the popularity of western stories with the mass media was in part serendipitous. Anglo-American settlement of the West happened to take place simultaneously with the rise of penny newspapers, dime novels and sensational journals, such as the ‘National Police Gazette’.”

Wister was among an assortment of troublesome young “remittance men” from rich Gilded Age families (a number of whom washed up on the shores of Puget Sound with descendants living here today), who were maneuvered via financial support from their families to live as far away as possible from East Coast culture that distained new immigrants and racial minorities, and questioned their sons’ “masculinity”– irresponsible or otherwise.

White explains how this is displayed in “The Virginian”: “Wister’s cowboys got drunk, frequented prostitutes, gambled, slept with other men’ wives, and killed each other, but their life of violence was ‘pure.’ Beneath the plot of “The Virginian” ran a subtext of inequality of human beings that shone through.”

Dr. White’s assessment of upper-class East Coast Wister’s warped view of the “West” states that for Wister, “‘… quality rises above inequality.’ To do so, the ‘quality’ [White Anglo-Saxon males] has to use means unsuited to a civilized society.”