A previously little-known sentence in one of the Constitution’s post-Civil-War amendments is suddenly in a national spotlight. That section in the 14th Amendment may disqualify Donald Trump from becoming President again. Citing the amendment, lawsuits have already been filed in a couple of states to keep Trump off the ballot.

Inevitably, people who have always detested Trump say he should indeed be disqualified. People who have supported him say the Democrats would love to see him disqualified because they’re afraid he’ll win. Both are right.

The idea of using the amendment to ban Trump was floated a couple of years ago. It has gained urgency with the first stirrings of the 2024 campaign, and it has gained gravity since two conservative constitutional scholars, William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen — members of the Federalist Society, no less — have written a law review article arguing that his actions on and round the January 6 Capitol Hill insurrection disqualify him. Other reputable legal scholars, including Harvard Law School professor emeritus Lawrence Tribe, have agreed.

Can the 14th Amendment really keep Trump out? Should it?

First, the basics. The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, only three years after the Civil War. Its first section says that no state may “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” This “equal protection” language was the basis of the Supreme Court’s unanimous 1954 Brown decision that scrapped the “separate but equal” doctrine in public education, ruling that separate was inherently unequal. It also underlAY the majority opinion in Roe v Wade.

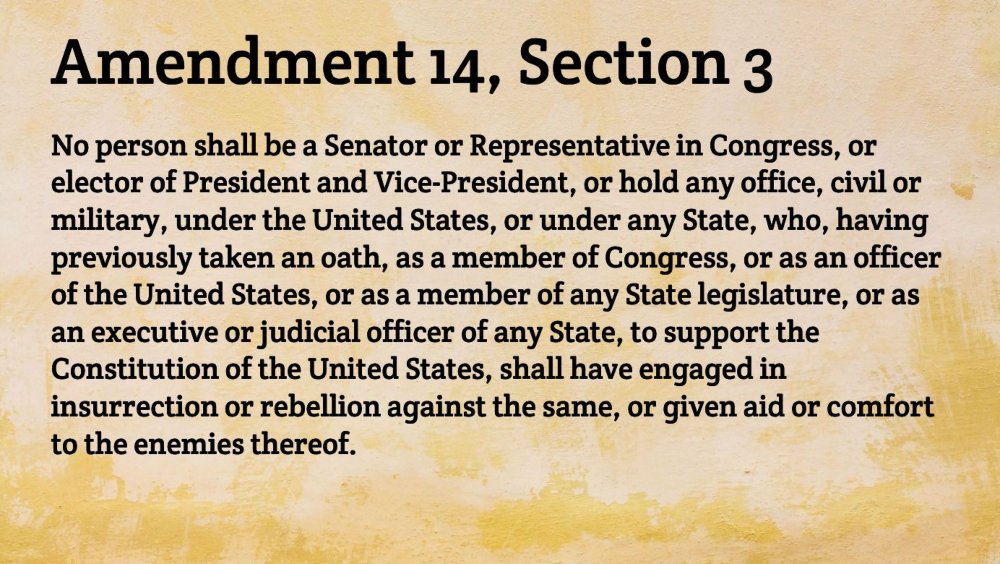

But Section 3 is the part of the amendment that may decide the political fate of Donald Trump. It says: “No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.” It adds, though, that “Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.”

It was aimed at a problem very much of its time, but it was written generally enough to apply to ours. The target was Southerners who had served in the federal government (the Confederacy’s president, Jefferson Davis, had been a Congressman, a Senator and U.S. Secretary of War) or U.S. military (Robert E. Lee, the Confederate commander who surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant, had been a general in the United States army and a supervisor of the U.S. Military Academy) and had taken oaths to defend the Constitution. They had violated their oaths when they became officials or officers of the Confederacy. After the war, they were ready to return to Congress and to positions of state leadership. For the time being, the winning side wasn’t about to let them.

(Most people in their home states had never voted for them. Women, of course, couldn’t vote there or anywhere else. Former slaves couldn’t vote yet, either. Their right to do so stemmed from the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870.)

Asking whether or not the language can or should be applied to Trump raises a host of questions, some legal, some political, and some, I would argue, historical.

Deciding who qualifies for a primary or general election ballot is done at a state level. Therefore, unless federal courts take over the decision-making process, the first-level decisions will be made by secretaries of state. Some will no doubt rule against Trump (anyone who does will probably face death threats), others rule for him. Courts will have to sort it out.

Officials in some states are already coming under pressure to act. In Colorado, a small group of Republicans and independents, represented by a Washington, D.C. non-profit, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics, has sued the Colorado Secretary of State to keep Trump off the primary ballot. This isn’t the first 14thAmendment suit, but it’s reportedly the first well-funded one. Now, a similar suit has been filed in Minnesota. The Colorado plaintiffs’ complaint describes a sprawling web of efforts, starting well before January 6, to undermine the Constitutional transfer of power. It describes the use of threats, intimidation, violence, public misrepresentations, and cynical subterfuge.

Does this all add up to “insurrection”? A number of the January 6 rioters or their absent leaders have been convicted of “seditious conspiracy” – which certainly overlaps with insurrection but doesn’t automatically make anyone an insurrectionist. Special counsel Jack Smith hasn’t charged Trump with insurrection. Neither has Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis.

Not that a legal finding is necessary to use the 14th amendment against Trump. The definition of “insurrection” remains vague. To the people who lived through the Civil War, it was obvious. In the early 21st century, it falls into a gray area, as does the definition of “aid and comfort.” Such things may seem highly subjective — like stereotypical definitions of art “I know it when I see it” or jazz, “if you have to ask, you’ll never understand.” Without clear standards, anyone’s definition might perhaps be too vague to support a conviction in a court of law. But (in theory) the 14th Amendment doesn’t require a court of law. And it doesn’t require that kind of precision.

“[A] conviction would be beside the point,” Lawrence Tribe and retired federal appeals court judge Michael Luttig have written in The Atlantic. “The disqualification clause operates independently of any such criminal proceedings and, indeed, also independently of impeachment proceedings and of congressional legislation.”

Besides (which may or may not prove relevant) a lot of other people have acknowledged that an insurrection certainly took place. “A bipartisan majority of the House of Representatives impeached Trump for ‘incitement of insurrection,’” the Colorado complaint says, “and a bipartisan majority of the Senate voted to convict him, with several Senators voting against conviction (and the final vote falling below the requisite two-thirds supermajority) based “on the theory that the Senate lacked jurisdiction to try a former president.”

“The bipartisan January 6th Select Committee and numerous federal judges have likewise recognized Trump’s central role in the insurrection. Courts have disqualified officials under the Fourteenth Amendment who played far less substantial roles in insurrections, and who, like Trump, did not personally commit violent acts. This includes Couy Griffin, a former New Mexico county commissioner who was a grassroots mobilizer, inciter, and member of Trump’s mob on January 6 (but did not commit violent acts or breach the Capitol building), and Kenneth Worthy, who served as a sheriff in a Confederate state (but did not take up arms in the Confederate army). If these individuals’ conduct warranted Section 3 disqualification, then surely Trump’s does as well.”

As for Trump’s giving “aid and comfort” to insurrectionists, the complaint notes that “[s]ince January 6, 2021, Trump has publicly affirmed his disloyalty to the Constitution and his allegiance to the insurrectionists who seized the Capitol for him. He has called the insurrectionists ‘patriots,’ vowed to give many ‘full pardons with an apology’ if he becomes President again, financially supported them, released a song with a choir of convicted January 6th defendants called ‘Justice for All,’ and hugged on camera a convicted January 6th defendant who has said that Pence and Members of Congress who voted to certify

Biden’s victory should be executed for treason.”

The complaint echoes the observation made by Baude and Pauisen in their law review article that having participated in an insurrection or having given aid and comfort to those who did simply disqualifies a person from holding office just as, in the case of the Presidency, being less than 35 years old or being born in a foreign country does.

“You are disqualified, period,” Tribe has explained. The constitution “couldn’t be clearer.”

“[T]here is a list of candidates and officials who must face judgment under Section Three,” Baude and Paulsen say. “Former president Donald Trump is at the top of that list, but he is not the end of it. . . . [I]t is not for us to say who all is disqualified by virtue of Section Three’s constitutional rule. That is the duty and responsibility of many officials, administrators, legislators, and judges throughout the country. Where they are called on to decide eligibility to office, they are called on to enforce Section Three, applying the Constitution’s legal standard to the facts before them in a given instant.”

But who applies it? “Opponents of [using] the 14th Amendment against Trump argue that state election officials do not have the authority to bar candidates,” Maegan Vazquez has written. “They are also arguing that Trump did not engage in an “insurrection,” that Section 3 should not apply to a candidate before an election and that an act of Congress is needed to enforce Section 3. Legal scholars have also raised questions about whether a former president who has never served in another office counts as an “officer” under the clause.”

Indeed, a former United States attorney general, Michael B. Mukasey, has argued that the 14th amendment disqualification doesn’t even apply to Donald Trump or his Presidential bid. While most people seem to believe (quite logically) that “officer of the United States” clearly includes the President, he says no, that it applies only to appointed officials. Therefore, the other questions raised about how or whether the 14th Amendment should be applied are simply moot. Period.

So we have these questions with answers that should be obvious but aren’t. Was there an insurrection? Did Trump either engage in it or give aid and comfort to those who did? Was he an officer of the United States to begin with? Does it matter that Section 3 never explicitly mentions the president?

All of which leads to the question of whether invoking the 14th Amendment is politically wise. Some thoughtful critics of the idea argue that keeping Trump off the ballot would not only affect him; it would keep millions of Americans from voting for the candidate they prefer. True, it would. But then, that’s really the whole point of Section 3: The people who had put Confederate traitors into positions of power before the war, were eager to – and had in fact started to – put them right back in office now that the war was over. Section 3 is all about denying people that choice.

Politically, even felony convictions probably won’t shake the faith of people who treat Trump as a cult leader, since they won’t be swayed by anything alleged or proven. Legal action against him has been regarded as further proof that they are out to get him – no less an authority than Vladimir Putin has called Trump’s legal problems the results of “persecution” — and maybe, as Trump says, the persecutors themselves will be next. Trump has set up a situation in which no one who opposes him can win a victory that his supporters consider legitimate. He has said before both his Presidential races that he could lose only if the election was rigged. (Heads I win, tails you cheated.) And he has encouraged people to believe that if he is indicted for a crime or tort, it’s only because the legal system has been weaponized against him.

Historically, as many people have pointed out, efforts by Trump and his acolytes – some true believers, others merely cynics – to overturn the 2020 election results have no precedent. Storming the Capitol, strong-arming state and local election officials, trying to short-circuit the certification of legitimate votes, and arguing that the election had been “stolen” all undermined the Constitutional political system that generations of American school kids have learned about as a point of national pride.

But the nation hasn’t responded to a Constitutional crisis by invoking a Constitutional remedy. Invoking it would probably open the door to years and maybe generations of outrage, bitterness, violence, loss of faith in the judicial system, and very likely, attempts to use the constitution for political ends. Arguably, those horses have already left the barn.

And what are the alternatives? Juries in Georgia, Florida, and/or Washington, D.C. may find Trump guilty of various crimes, and appeals courts may ultimately sustain the verdicts, but that may or may not happen before elections are held, and in any case, felony convictions wouldn’t keep him off the ballots.

Discussing the former President’s legal troubles, Trump lawyer John Lauro has said publicly that his client may have committed a technical violation of the Constitution, but that doesn’t mean he broke any criminal law. Which is technically true. But a “technical violation” of the Constitution? This is a defense?

People now speak now of the South losing the Civil War but winning the subsequent narrative. The myths of the old South such as the lost cause have lived on. Yahoos still brandish Confederate flags. What will be the narrative of how this nation dealt with Trump?

Personally, I’m rooting for THE 14th Amendment to disqualify Trump. Despite the reaction of Trump and his supporters. But I’m not holding my breath.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Not so fast Dan. It’s not clear if Section 3 is self executing, or if legislation would be required. Usually Constitutional provisions are not self executing. Also, Section 3 could only disqualify Trump if the oath he took on January 20, 2017 he was “an Officer of the United States.” On that date he was not.

Even law professors and Judges are arguing about these things and more. Not quite so fast.

Here are the new developments in California, where the Democratic attorney general is leading the charge. Can Washington state and Bob Ferguson be far behind? https://www.politico.com/news/2023/09/18/democrats-effort-kick-trump-off-california-ballot-00116476

Disqualification on the grounds of 14th Amendment semantics is a very thin reed, wholly befitting of an Obamaian, Alynskian, or Bolshevik tactic.

If you want citizens to have confidence in election results, then election integrity is essential. One man (or woman), one vote (per eligible person), one day (vice weeks of open season) would help to rebuild trust in election results.

We do have a precedent to consider: Infamous, colorful Boston Mayor won an election while in jail, and had a stay in office interrupted by a stay behind bars.

Sprung due to health worries, “the Curley” lived another decade.