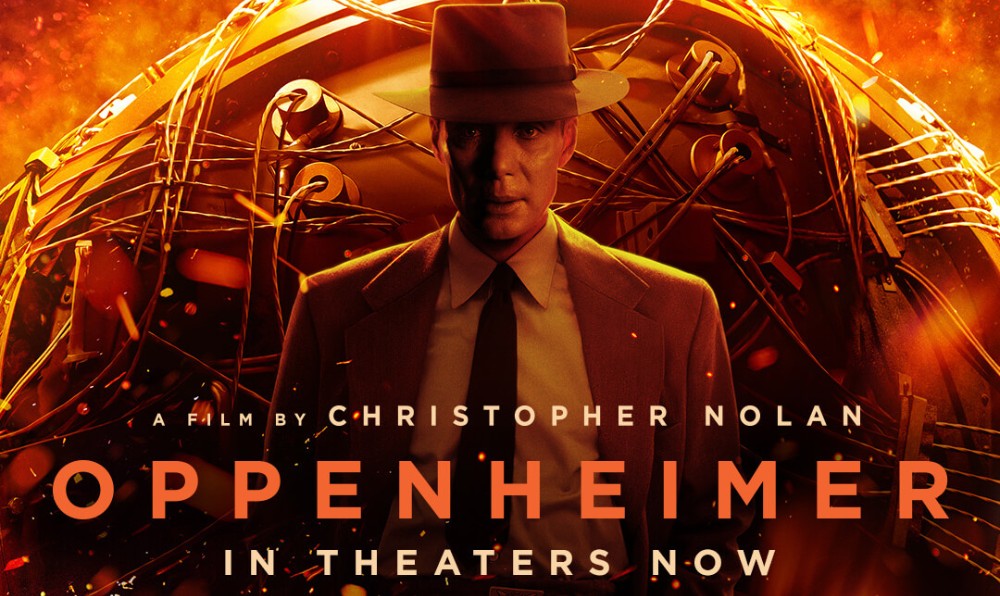

The blockbuster release of the popular film Oppenheimer gives Americans a chance to re-visit the complicated history of this nation‘s development, testing, and use of nuclear weapons during World War II and the long Cold War that followed.

The movie isn’t entirely accurate, some people have pointed out, and it leaves out certain accomplishments and outrages. But that doesn’t mean the people who say, “yes, but” should be ignored. If we’re going to revisit the world-changing early decades of nuclear weapons, people should recognize the historic importance of eastern Washington’s Hanford nuclear site, and we should all realize that our government exposed thousands and thousands of its own citizens to radiation from airborne waste and the fallout from nuclear tests.

Oppenheimer turned out to be a “missed opportunity,” Tina Cordova wrote in The New York Times. It ignored the people living downwind of the Trinity test who were exposed to radiation, and the miners who extracted the uranium that Hanford made into plutonium for the blast. (Uranium miners, many from indigenous communities in the Southwest, faced high odds of developing lung cancer, particularly for smokers.) “A new generation of Americans is learning about J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project,” Cordova wrote, “and, like their parents, they won’t hear much about how American leaders knowingly risked and caused harm to the health of their fellow citizens in the name of war. My community and I are being left out of the narrative again.

“The area of southern New Mexico where the Trinity test occurred was not, contrary to the popular account, an uninhabited, desolate expanse of land. There were more than 13,000 New Mexicans living within a 50-mile radius. Many of those children, women, and men were not warned before or after the test. Eyewitnesses have told me they believed they were experiencing the end of the world.”

Hanford produced not only the plutonium that exploded at Trinity but also the plutonium that exploded over Nagasaki and at the South Pacific atoll of Bikini, and the plutonium in bombs that American strategic bombers carried during the Berlin crisis and the Cuban missile crisis, and the plutonium used in the test explosions that irradiated those thousands of American citizens.

A dubious legacy perhaps, but a significant one. Yet the film didn’t give any attention to Hanford, Steve Olson, who has written a history of Hanford, wrote in the Seattle Times, and it didn’t recognize the stupendous feat of building and operating the first Hanford reactors in just a couple of years, much less the drive and ingenuity of the people – including Olson’s own pipefitter grandfather – who built them.

Olson suggests that “the most audacious feats of science and engineering actually took place not in New Mexico . . . but on a barren, windswept plain in Eastern Washington.” Maybe. The plutonium manufactured at Hanford certainly changed the world. Olson notes that “when scientists recently proposed a dividing line for the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch that marks the onset of humanity’s influence on the Earth, that dividing line was the appearance of plutonium, in part from Hanford, in the sediments of a Canadian lake.”

Hanford was indeed the first plutonium factory in human history. Like it or not, that arguably makes Hanford the most significant historical site in the Pacific Northwest. (If you like, you can add to its credentials: that the nearby Tri Cities area includes the spot at which Lewis and Clark first saw the “River of the West”; the spot at which two guys at a hydro race found the remains of Kennewick Man; the headquarters from which an overmatched board of directors launched and kinda-oversaw the WPPSS nuclear construction fiasco, in which a consortium of public utilities failed to complete four out of five planned reactors and wound up triggering what at the time was the largest municipal default in U.S. history.)

And, oh yes, Hanford remains the most contaminated radioactive waste site in the Western Hemisphere.

Washington‘s connection to the Oppenheimer story goes beyond Hanford – and beyond plutonium. Seth Neddermeyer, who advocated for and at first ran the group working on the implosion method of detonating a nuclear bomb – the method that was used successfully in the Trinity test and over Nagasaki – wound up teaching physics at the University of Washington (where, among other things, he pursued an interest in paraphysics.)

Louis Strauss plays an important part in the film as the guy who engineered Oppenheimer’s loss of his security clearance in 1954. Strauss was subsequently voted down by the Senate when he was nominated to become U.S. Secretary of Congress. The Senate rejected him after a hostile hearing before the Senate Commerce Committee — portrayed in the film – which was chaired by Washington Sen. Warren Magnuson.

Shortly after Oppenheimer lost his federal security clearance, the University of Washington physics department suggested inviting him to the UW campus to deliver the Walker Ames public lectures. The university’s president refused. (Washington went all-in on anti-communism in those days. When a 1955 law required all UW employees to sign loyalty oaths, some employees sued. In its 1964 Baggett v Bullitt decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the law was unconstitutional.

Beyond the interpersonal and scientific dramas portrayed in Oppenheimer, we still have the radioactive fallout from bombs fueled with Hanford plutonium and the release of airborne radiation, some deliberate, created by the plutonium-making process. Radioactive iodine entered the air from a Hanford smokestack in the 1940s and the early 1950s. Prevailing winds carried it east, where people lived. Most of the discharges were known but incidental. The “Green Run” of 1949 was different: A cloud of radioactive iodine and xenon was deliberately released so that scientists could track it and learn lessons that might help gather information about Soviet nuclear tests. Several thousand eastern Washington “downwinders,” some of whom had thyroid cancers, underactive thyroids, or thyroid nodules, sued for compensation. Litigation dragged on for 24 years. It finally ended in 2015, an unknown number of plaintiffs had settled, and two received jury awards that totaled $545,000. The plaintiffs’ lawyer complained that the amounts his clients received were “very unreasonable.” (It hadn’t helped their cause when a Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, in a study managed by the CDC, found no excess cases of thyroid cancer disease in the downwind population.)

It was worse in Utah. I used to spend a fair bit of time in St. George, Utah, where my in-laws lived for many years. The landscape is striking, full of red rock and distant mountains, close to Zion National Park and the north rim of the Grand Canyon, only a couple of hours drive from Las Vegas. It now has a university, golf courses, and many thousands of retirees – who presumably chose the location without much thought of radioactive fallout.

But back in the day, before the freeway, residents would gather on high points in the night to watch nuclear blasts at the Nevada test site, like people watching fireworks on the Fourth of July. Hanford plutonium produced a lot of the nuclear fireworks. Nevada lay to the west, so prevailing winds carried the fallout east where it settled down on people, houses, and gardens in St. George. Perhaps 60,000 people were exposed. A lot wound up with leukemia.

There was no way to prove that any individual case of cancer had been caused by fallout. But the incidence of cancer in the population was unusually high. It took a long time for the federal government to acknowledge that and to pay some compensation to victims and their families. In 2000, Congress passed legislation to compensate survivors and the surviving families of Southwestern residents who had contracted leukemia and other cancers after exposure to radiation. The bill also compensated survivors and surviving families of the men who mined uranium. The people had been exposed from the 1940s, through the 1960s. The compensation had been a long time coming.

The people exposed weren’t all civilians. Years ago, when my wife was working as a bone marrow transplant nurse, she was surprised to learn that an older patient’s cancer may have been related to the time in the 1950s when, as a young American soldier, he had been sent into the blast zone of a nuclear test explosion in the Nevada desert. She hadn’t heard about the “Desert Rock” experiments to see how soldiers functioned — and train them to function — on a nuclear battlefield. But the government carried out six sets of maneuvers in the 1950s to do just that.

The government didn’t get the informed consent of the people who were exposed to radiation deliberately or through deliberate indifference. Yes, the United States was engaged in what people rightly considered existential struggles against Nazi Germany and imperial Japan and then against Stalin’s Soviet Union. There was a sense of urgency. The immediate took precedence over the long-term. And yet, at least with hindsight, it’s hard to justify what went on. Granted, people generally underestimated the dangers of non-lethal doses at that time, and also underestimated the need for consent. The Hanford downwinders’ attorney said in 2015, “[i]t could not have escaped [the federal Department of Energy] that people were definitely subjected to radiation kept secret from them until 1988.”

Of course, people all over the Northern Hemisphere were irradiated at least a bit by the atmospheric nuclear testing – banned by treaty in 1963 – carried out by the U.S., the USSR, and France. Studies in the late ’60s found radioactive Strontium 90 in the breast milk of Arctic mammals, including polar bears, caribou, beluga whales — and human beings.

What about all the radioactive waste that accumulated at Hanford over more than 40 years of plutonium production? It’s still there: Hanford is the nation’s largest environmental cleanup site. It’s no secret that in the heat of World War II, the government didn’t waste much time or money on taking out the garbage. Dangerous radioactive waste wound up in crappy single-walled steel tanks.

At Hanford, a lot of waste still lay in those old single-walled and in some cases leaky tanks. In 1973, around the time Hanford announced one of the old tanks had leaked 115,000 gallons, Hans Bethe, who had won his Nobel Prize for figuring out the nuclear reactions that powered the sun – and who figures in the film as the head of the theoretical physics division at Los Alamos — was teaching for the summer at the UW. Weeks before the leak was announced, a friend who taught physics at the university invited me and Bethe to lunch.

The conversation turned to nuclear waste. There were plenty of ways to dispose of it safely, Bethe argued; What we lacked was the political will to choose one. But surely, I suggested, just stuffing our radioactive garbage into tanks was a bad idea. Bethe disagreed. No, he said scornfully, “only cheap tanks leak!” Which, of course, turned out to be at least part of Hanford’s problem

In 1987, the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the State of Washington signed an agreement that required the DOE to meet certain cleanup targets by certain dates. Those targets haven’t been met. The worst of the waste was supposed to be extracted from tanks, encased in glass at a huge vitrification plant — which was supposed to be completed by now — and sent to a federal nuclear waste repository at Nevada’s Yucca Mountain.

But people in Nevada didn’t want the waste, Nevada’s Harry Reid was opposed, the Obama administration didn’t want a fight with Reid, and the plan to store waste at Yucca Mountain was scrapped. Now, with estimated cleanup costs of more than half a trillion dollars, the feds are talking about just leaving a lot of the waste at Hanford. Forever.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s great novel, The First Circle shows the ruthless Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin saying repeatedly, “you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” Back in the day, that seems to have been the de facto philosophy of all the nuclear nations, including this one. If we’re going to take a real look backward at Oppenheimer, his impact and times – which the release of the movie invites — that and much of the above should be part of the story.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Anyone who has read the Oppenheimer literature, bookshelves of it, could add to what Mr. Chasen has written. It takes a book, often multiple books over time to get the measure of a period as complex as the beginnings of the nuclear age and a man like Oppenheimer. I have many friends and acquaintances who say similar things to Mr. Chasen’s approach when they discuss TV or streaming “documentaries”.

“It’s a movie” is my answer. Even when the movie is “taken from a real story” or “life”; it’s still a “movie” compacting time into a time period as restrictive as a shoe that is too small. Even multi-part productions, hours and hours, are still well short of what a book can produce. Ask any film-maker or documentarian who has done the necessary research for the ratio of what was left out versus what got into the final product. Begin with 10 to 1 and go up from there.

The only successful approach when you tune in or go to the theatre is to understand that what you see and hear will be selective in the extreme versus what may or may not have happened.

Excellent analysis, Dan Chasan.