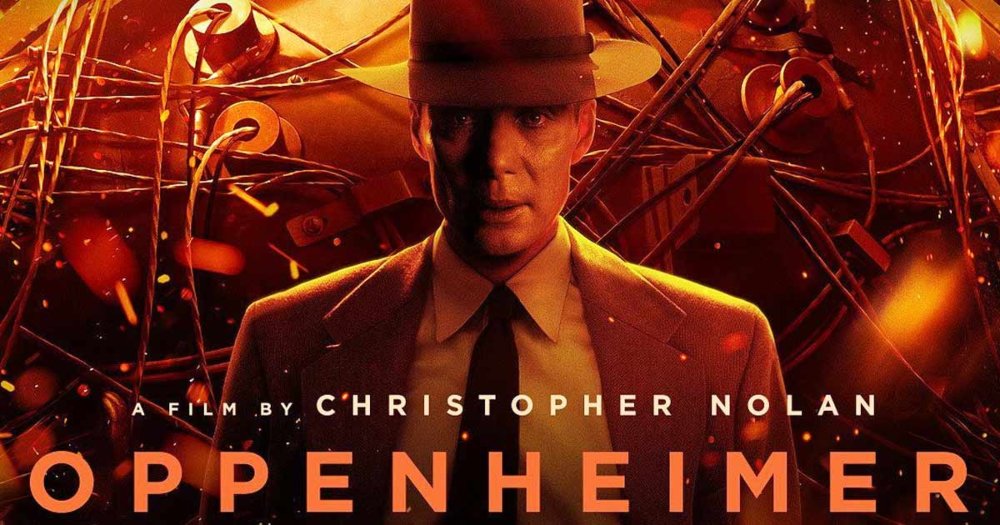

The praise of the new film “Oppenheimer” leaves me ambivalent. It’s a good story, well-acted. The narrative line, however, is chopped up between earlier and later, with one thread in color and the other in black and white. There are reasons for that, but mixing a story about a man with a story about a bomb and a story about Communism and loyalty sometimes makes it hard to follow.

Several famous people — Gen. Leslie Groves, Albert Einstein, Edward Teller, Werner Heisenberg — are important characters, and other famous people — Leo Szilard, Hans Bethe, Klaus Fuchs — are shown briefly. I looked around the theater: Did the audience know who all these people were? The script (and maybe some subtitles) could have helped a lot more. The picture introduces Groves (played by Matt Damon) well, but that’s not true for most of them.

The movie had a lot about Oppenheimer’s personal life, including his sex life. You expect that from Hollywood. But it has only a little about the technical problems in inventing the bomb, and how Oppenheimer’s team solved them. Hollywood doesn’t think viewers care about the technical parts.

Then the Communist issue. Much of the film is about how in the mid-1950s, Oppenheimer was accused of having been a Communist and was stripped of his security clearance. The film does show that in the late 1930s, when you could be a Communist and a New Dealer at the same time, and American Communists were loud opponents of fascism, Oppenheimer had, in fact, been a Communist sympathizer. It showed that his first wife was a party member who tried, and failed, to get him to join.

It shows Oppenheimer resisting Gen. Groves’ security measures — because Groves is trying to corral scientists, and they resent military interference in their work. In all this, the film does mention that Oppenheimer’s colleague Klaus Fuchs (who was not an American) was, in fact, a Soviet spy. It shows Oppenheimer being asked by an American colleague to slip information to the Soviets, and declining — but not reporting the incident to Gen. Groves.

The film defends Oppenheimer as a loyal American who was hounded out of a position of respect and trust. That’s accurate. The Red Scare was a shameful episode in American history because it was overdone. The shame part is a lesson that Hollywood and academia especially like to tell — because they were targets of red hunters, and their politics have long leaned to the left. What we don’t get out of Hollywood are the stories in which the “scare” was justified: the big Communist spy cases of the 1940s and early 1950s, especially the cases against Alger Hiss, Judith Coplon and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Those stories have a different lesson — that some American Communists were, in fact, spies for Stalin; that when they were publicly accused, many liberals and progressives of the day defended them. And on that point the liberals and progressives were wrong.

If you doubt that, read the books that have been written about all these cases, such as Beverly Gage’s G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century, published last year. In the Hiss case, for example, Gage writes, “Everyone took the side that best fit their own assumptions” — the liberals saying Hiss was innocent and the conservatives saying he was guilty. And about Hiss, the preponderance of the evidence is that the conservatives were right. But about Oppenheimer, they were not.

The Hiss case, in particular, would make a fabulous three-hour movie of the same rank as “Oppenheimer.” Better than “Oppenheimer,” I think. The only attempt to tell that story that that I know of was the four-part, 3-hour, 39-minute TV miniseries called Concealed Enemies. It was produced in 1984 by American Playhouse and shown on PBS. It has Peter Riegert as a worried and calculating Richard Nixon, Edward Hermann as an self-assured and outraged Alger Hiss and John Harkins as Hiss’s long-suffering and deeply troubled accuser, Whittaker Chambers.

Concealed Enemies was produced before anyone had support from FBI and Soviet archives that Hiss was in fact a Soviet agent, which is now conceded by most historians. Concealed Enemies tries to play the story right down the middle. In hindsight, it was too credulous regarding Hiss, but it is still a gripping account — dark and foreboding, loaded with personality and drama.

Concealed Enemies won an Emmy award. On the Internet Movie Database it is rated 8.3 out of 10 — but by only 49 people, because it never came out on VHS or DVD. In 2003, a user wrote on its IMDb page, “Years ago this excellent and riveting mini-series was shown on late night Australian TV for the first and last time. Why is it never shown anymore and why isn’t it available on video? If an Emmy award doesn’t justify showing something of this quality more than once what does?” Twenty years later, it’s still a good question.

Regarding the “Red scare” period, Hollywood gives us Trumbo (2015, IMDb 7.4, rated by 83,000 people), in which Brian Cranston plays a famous screenwriter who was blacklisted for being a Communist. Trumbo was a master of his craft; he later was the principal screenwriter for Spartacus (1960). When Hollywood makes a movie about the anti-Communist period it most often concerns people who were falsely accused (like Oppenheimer) or who were accurately accused but were no threat to national security (like Trumbo). To Hollywood, the “Red Scare” was a witch hunt — a term that implies that it was the pursuit of an imaginary danger.

But in some big, important cases, it was not imaginary at all: the cases of Hiss, Coplon, and Rosenberg especially, but also Elizabeth Bentley, Julian Wadleigh, Harry Dexter White and others. In Concealed Enemies, Wadleigh (played by Frank Maraden) nervously admits to passing State Department documents to the Soviets in the late 1930s. But the Communists were fighting fascism then, he says in a tormented voice, in the civil war in Spain — and nobody else was. And in World War II, the Soviets were our allies.

My memory of the Wadleigh character in Concealed Enemies is that he sounded not too different from Oppenheimer, except that Oppenheimer was innocent and Wadleigh was not. Each story is true. Hollywood tells us one and not the other.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for your review of Oppenheimer. It was hard for the audience to know who all the people are, except for me who grew up in Los Alamos in the 40s, 50s and 60s. My earliest memory is arriving at the gate to Los Alamos where my parents had to show a security badge. Growing up in Los Alamos was unique. Our education was like a STEM school. Personally I went on to become at nurse at Fred Hutch where I was lucky to continue to work with scientists.

Careful, Bruce. You know the one thing your critics can never forgive you for is being right. Watch your back!

Time for local journalists such as Ramsey and Junius Rochester to do some digging closer to home. In 1953 then-UW President took his lead from local “Red-baiters” such as former U.W. law school dean Al Schweppe and cancelled Oppenheimer’s invitation from the Physics Dept. to speak as the Walker=Ames Lecturer.

Seattle and Washington State were hotbeds of “anti-Communist” fear-mongering post WW II, linked directly to the GOP. Some of the most outspoken (along with Spokane one-term legislator Al Canwell) were ultra-conservative attorney Schweppe and Seattle city council member Mildred Powell who had the good sense to “resign” to become a full time crusader for her red-baiting non-profit in 1955. Clearing the way for LWV president Myrtle Edwards to join the council. That was a few months after Sen. Joseph McCarthy was censured by the U.S. Senate and a majority of Americans were tired of this sort of hysterical ranting. But before that moment, a number of UW profs were smeared, with support from the Seattle Times. Seattle’s good luck was that Times journalist Ed Guthman (he later moved on to a better paper) began digging, found the right-wing anti-communist folk had hidden information and after many good people lost careers and money, brought the truth to light. Book to read: False Witness. Here’s a link from UW Archives:

https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/pioneerlife/id/24222/#:~:text=Robert%20Oppenheimer%20was%20nominated%20and,appointment%20in%20December%20of%201954.

I’ve read “False Witness.” The Seattle library has it. The book is the rebuttal of former University of Washington Philosophy Prof. Melvin Rader to the testimony of George Hewitt, former member of the National Committee of the Communist Party. The Canwell committee brought Hewitt to Seattle from New York to testify here in 1948. Hewitt identified Rader as having been a Party member because he remembered seeing Rader’s face at a Communist “School” held on an upstate New York farm a decade earlier, in 1938 or 1939. Hewitt wasn’t sure which year, and he did not remember the name “Rader,” only the face.

It was not strong testimony and it was not backed up anyone else. The Canwell committee interviewed several other ex-Communists from around Seattle, and asked them about Rader, and every one of them said they believed Rader had not been a Party member. Also, Rader declared that he had not been a member. Others accused of being CP members generally refused to answer the question, and Rader did answer it. And in False Witness, he argues that he never went to New York during those years, and was involved in other things. I conclude that Hewitt either had a faulty memory or was bearing false witness.

But the other testimony at the Canwell hearings made it clear that before the war, Rader had been involved a front group created by the Party, the League Against War and Fascism. Back then, the Communists were hot to fight the Nazis — until the Hitler-Stalin pact of August 1939, when suddenly they were for “peace.” Some of their American supporters made that U-turn and some didn’t — and Rader did, in print. Whether he should have lost his professorship a decade later is another question. But in False Witness, I don’t recall him owning up to having sided with Stalin, or admitting that he had been wrong about it.

What seems to be missing here is a recognition that Americans are entitled to hold a variety of views. What business did a committee have, trying to determine whether Rader did “side with Stalin”?

In the article, this point seems to be restricted to real treason, in the form of spying. That’s one thing; ideological leanings are another. The dread of Communism has been turned into a political Pavlov’s bell that still a century later makes people foam at the mouth.

My Correction – Book cited “False Witness” is not correct. The UW archives outlines Schweppe’s position on this issue.

Thanks Mr. Ramsey for that correction/addition/summary of my cautious book title correction – as I did not trust my memory on short notice. What is worth noting today is how virulent anti-communism was in post-WW II Washington State. It sat at the University of Washington’s high table of administrative power and on the City Council, aided by the unfortunate influence of Atty. Schweppe. This caused a shameful “piling-on” directed at J. Robert Oppenheimer in once-upon-a-time Seattle.