Richard Hugo enjoyed a cold brew and idle chatter with friends. This convivial pastime was integrated into his verses and books. His favorite bar scenes were at-the-other-end-of-the-road in Washington state and Montana.

Born Richard Franklin Hogan on December 21, 1923, in White Center, Washington, Hugo took his B.A. and M.A. at the University of Washington. His first exposure to poetry was taught at the University by the future Pulitzer winner Ted Roethke.

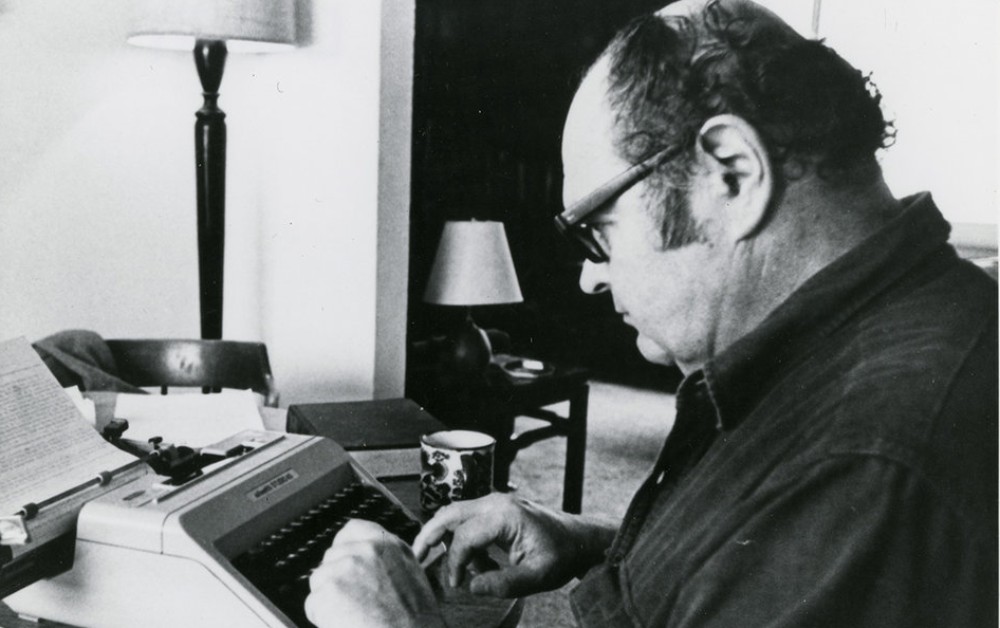

During the 1960s and ‘70s Hugo taught and wrote in Missoula, Montana, home of the University of Montana. Upon his death from leukemia on October 22, 1982, Richard Hugo left behind 13 books, most of them filled with poetry and essays. Much of that work described the people he knew at old-town bars, baseball, fishing, and various forgotten corners of the Pacific Northwest.

In 1986, I attended a symposium at the University of Washington celebrating Hugo’s life and work. During that session, I picked up a freshly printed book of essays by Hugo which had been more-or-less organized as his autobiography. The book was ingeniously titled The Real West Marginal Way.

West Marginal Way is a north-south artery bordering the heavily industrialized (and polluted) Duwamish River. West Marginal Way threads its way to and from Hugo’s hometown of White Center. One of his poems, entitled “West Marginal Way,” reads in part: “One tug pounds to haul an afternoon of logs upriver. The shade of Pigeon Hill across the bulges in the concrete crawls on reeds in a short field, cools a pier and the violence of young men after cod. The crackpot chapel, with a sign erased by rain, returned before to calm and a mossed roof.”

Hugo remembered the immigrants and aboriginal people who lived in struggling communities along the Duwamish River. Those forgotten settlements, he wrote, were “more European in appearance than any other in Seattle.” He believed the stories about the Greeks who distrusted banks, the Slavs who bought cheap bourbon, and the feats of strength demonstrated by a fisherman called Old John.

White Center, Richard Hugo’s home, is split down the center by Roxbury Street. Just south of Roxbury could be found a row of working people’s taverns. A good time in that neighborhood, Hugo recalled, usually meant a good brawl. White Center, however, was not what he wrote about. Instead, he went to the Duwamish River to find his poems. Salmon derbies, bird sanctuaries, rowboats, his pal Don Crouse, brickyards, blackberry bushes, and tugboats — these were the stuff of his river poems.

Barely overcoming shyness, especially about girls, and pretending he was a tough guy, occupied many of Hugo’s youthful waking hours. After college, and then a year as a bombardier in the Second World War’s Italian campaign, followed by marriage, Hugo hit his stride as a sensitive teacher and poet. When his life shifted to the streams and mountains of Montana, the poems changed. Finding comfort and company in Missoula’s Milltown Union Bar – later called Harold’s Club — Hugo watched his stepchildren grow and his own weight increase into middle age.

In June 1982, Richard Hugo received an Honorary Degree, Doctor of Letters, and a Distinguished Scholar Award, both from the University of Montana. Four months later he died in Seattle’s Virginia Mason Hospital, not far from the sluggish brown waters of his Duwamish River next to West Marginal Way.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A compelling remembrance. I’ve attended events at Richard Hugo House and, I’m afraid to say, had no idea *who* Richard Hugo actually was. Now I’ve read this article and done additional poking around…what a great artist!

Richard Hugo was an extraordinary poet as well as an exemplary human with a huge heart and big brain. The lineation – where the poem breaks from one line to the next – changes the way a poem is read. Here’s “West Marginal Way” as Hugo wrote it:

One tug pounds to haul an afternoon

of logs upriver. The shade

of Pigeon Hill across the bulges

in the concrete crawls on reeds

in a short field, cools a pier

and the violence of young men

after cod. The crackpot chapel,

with a sign erased by rain, returned

before to calm and a mossed roof.

The last two stanzas of the poem send sparks through the imagination every single time I reread it. My favorite line in this poem is, “Some places are forever afternoon.” Wayne Horvitz used that line as the title of the album of 11 pieces of music, each inspired by a different Hugo poem. Definitely worth checking out more of Hugo’s poems, as well as the Horvitz’s suite in tribute to Hugo’s work.