Last session Washington state lawmakers enacted a number of new housing bills aimed at addressing the state’s persistent housing shortage. These new laws aim to expand the supply of “middle housing” types, streamline the creation of accessory (backyard) dwelling units, aid first time home buyers affected by past discriminatory practices, and curb some of the costly regulations and processes that hinder new housing development. Most of these regulations won’t take effect until mid to late 2025, approximately 6-12 months after the completion of the Seattle Comprehensive Plan Update.

The most immediate change will come from Senate Bill 5412. This bill, effective July 2025, will exempt all new housing projects from State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) review. This exemption will apply to all new projects going forward and will cancel SEPA reviews for all projects currently under way. For industry insiders this will immediately shorten permit review timelines and simplify the approval process, reducing costs to developers.

House Bill 1293 mandates that design review processes must be limited to a single public meeting, be based only on “clear and objective standards,” and that the review timeline must be concurrent or logically integrated with the overall building permit review. This is not just a tweak of the program, trimming its scope and timeline. In practice, it is likely to require a total transformation, if not outright elimination of Seattle’s Design Review program. These changes don’t have to take place until mid-2025, and it’s possible that they could be implemented sooner.

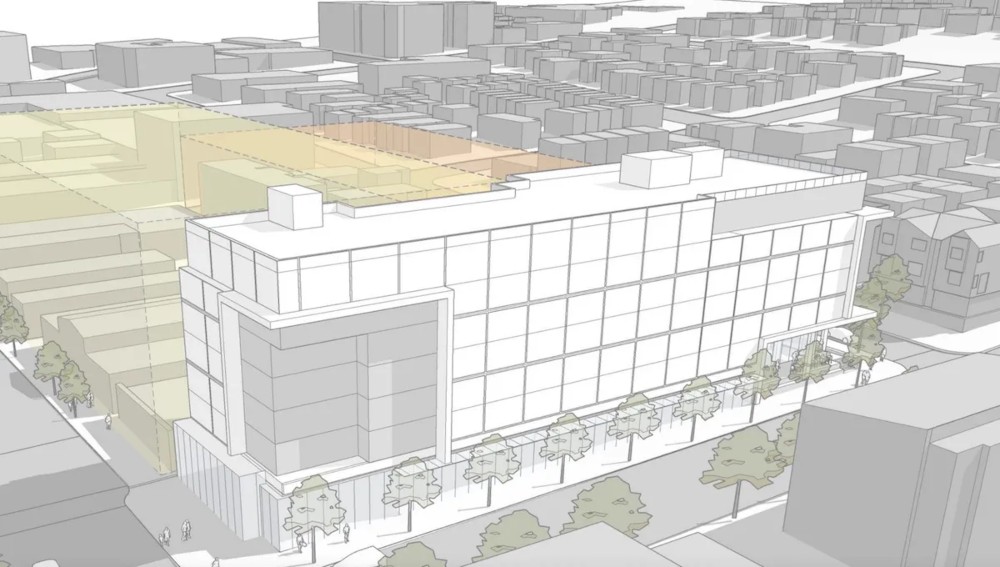

Currently, most new housing projects in Seattle larger than a few townhomes are subject to some form of Design Review. This review requires preparation of elaborate submission packets above and beyond the drawings needed for permit review. These packets often consist of 50-100 pages of maps, diagrams, illustrations, and renderings, resembling a cross between an elaborate pamphlet and a short book. The process typically adds about 8-12 months to a permit review, and in some notable instances, it can add years. Such reviews don’t jibe with real-world design process. The early guidance portion comes months after the applicant has settled on a design direction. Final reviews require applicants to commit to material choices and features long before the building design has been fully detailed and costs understood.

Frustration with the program’s effectiveness, cost, and dampening effect on housing development has led a broad coalition of housing advocates to call for the curtailment or outright elimination of Design Review.

As a former Design Review Board member and a frequent applicant, I am well aware of its drawbacks and some of its subtle benefits. While the process is an almost constant thorn in my side, it is also the devil that I know. I am excited about the prospect of this process being eliminated, but I am uncertain about what will replace it, and what the design and permitting process will look like on the other side of such changes.

SB 5412 requires three fundamental changes to the program. It requires guidelines to be based on clear and objective standards. It requires the process to be concurrent or logically integrated into the general permit approval process. Lastly, it allows a maximum of one public meeting. Let’s examine these changes individually.

Clear and Objective Standards: This seemingly innocuous requirement effectively renders Seattle’s Design Review Guidelines invalid. The current guidelines consist of open-ended prompts like “provide detail and human scale at street-level,” or “provide an appropriate transition or complement to the adjacent zones.” Objective standards, on the other hand, are akin to the language of the zoning code, which is clear enough that applicants can simply read the language and determine for themselves if they meet the standard. Subjective judgments do not apply in this context. It is difficult to envision how the existing guidelines could be modified to meet the criteria of being “clear and objective.” It is likely that such standards will be discarded.

Concurrent or Logical Review: Currently the design review process requires multiple sequential steps before submitting a building permit. These steps include Early Community Outreach, a Pre-Submittal Conference, an Early Design Guidance (EDG) public meeting, approval of the EDG, publication of a planner’s report, and submission of a Master Use Permit (MUP) application. None of these processes meet the new requirements for concurrent design review.

If the Design Review were to occur entirely within the building permit review window, it would be significantly different. Such a process would be limited due to SB 5412’s language, which restricts the scope of design review to the exterior design. Also, by the time a project is submitted for a building permit, it is already nearly fully designed and engineered. A design review program that attempted to reach back to address more foundational aspects of the design like building massing and site planning would not meet the requirement for logical integration with the general permitting process.

Only One Public Meeting: SB 5412 allows for only one public meeting, which would have to take place during the building permit review and focus solely on the discussion of clear and objective standards for the exterior design. Such public meetings would be nothing like they are today. It’s like being asked to critique a piece of music after that song has been recorded, with feedback limited to objective measures like the length of the song or beats per minute. Compare that to the high stakes open-ended meetings that are typical of the current design review program.

On the whole, these changes represent a big shake up in how housing permits are issued in Seattle. While there is hope for a radical simplification of the process, it is also possible that we could get a cure that’s worse than the disease. Here are some potential outcomes.

- Design Review is eliminated without a replacement, resulting in faster permitting, fewer regulations, and a more open field for housing development. This simplification would bring the permitting process back to the time before SEPA, and also incorporate 40 years of environmental protections.

- Creative semantic manipulation of concepts like “clear and objective” and “concurrent or logical,” is used to translate the current guidelines into a slightly more objective format and justify the current process as “logical” even if such maneuvers create process steps that are not concurrent with the building permit review.

- Design Review is discarded, but the design guidelines are replaced with new objective design standards within the zoning code. These standards would aim to codify rules for good design, potentially including requirements for complex variation of exteriors, changes in color and material, upper-level setbacks, and roof form. Seattle’s Design Standards for townhomes and Shoreline’s Design Standards provide some examples of how those might work. The new standards could consist of fixed universal requirements, or a menu of possible items from which applicants must choose. Projects that wanted to avoid the design standards could opt for some form of voluntary design review.

- Design Review is eliminated but replaced with an alternate form of public engagement. This might require early outreach, public meetings, public notices, informational websites, etc. While these processes could not be used to force design changes, they could require applicants to engage with the public, receive feedback, and publicly respond to it.

It’s hard to know exactly what direction Seattle might choose. While the elimination of Design Review would facilitate faster construction, which aligns with the intent of the legislation, the absence of a public engagement structure could trigger political backlash. Replacing Design Review with an extensive set of prescriptive rules, but it is unlikely that good design can be reduced to a set of cookie-cutter prescriptions. Earlier attempts to write zoning codes in such a manner had poor outcomes. I would hate to see us repeat that mistake.

There is also a possibility that the Design Review program continues on as a shell of its former self, where applicants are burdened with additional process steps while providing little meaningful influence on project outcomes.

I hope we can eliminate the program and replace it with some kind of one-stop public engagement website. This website could serve as a platform for applicants to upload project information, allow citizens to post public comments, and enable the city to distribute public notices to stakeholders who wish to stay informed. The goal should be to ensure that the public is well-informed about projects and has a means to communicate with the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) and applicants, without creating unnecessary costs or process steps that hinder new housing construction and architectural creativity. We have a maximum of two years to craft a solution, and I hope that we can prioritize and implement these changes ahead of the state deadline.

David Neiman is a partner at Neiman Taber Architects, specializing in multi-family housing design and development..

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nothing like “State preemption” is solve the housing crisis!

“Middle housing” (catch phrase) is a developer’s dream. As is the defacto elimination of a “design review process” and SEPA compliance.

And our legislators go home feeling good about themselves having struck a blow for the too often forgotten “middle class” which, of course, needs “middle housing.”

I agree that an expedited process was way overdue. Over years it had built on itself as governments resonded to one interest group after another by adding another step of process.

But as David Neiman says. Be careful what you wish for.

When I was EFSEC Chair the legislature, in its haste to support “green energy” effectively eliminated any State review of renewables resources. Everyone celebrated the first few wind turbines and solar farms. But now, not so much, especially if you live next to one.

Lesson learned: State preemption does not solve probelms. Too much process is bad; no process may be worse.

This just makes me uneasy, the thought of eliminating crucial steps of design review process, cumbersome though it no doubt is. I don’ t like the idea of a quickie, one-stop shop review process. It seems to move us backward in time, to a return of the brutalist low-income housing monstrosities of the 1960s. I agree with Jim, “no process may be worse.”

This subject could use a little more careful look at the legislation.

SB 5412 amended state environmental policy. What does that have to do with Seattle’s Design Review program? Nothing. Let’s get someone to look at what happened there and see if it actually does affect anything in Seattle. My guess is, not much. The points above attributed to 5412 are mostly not there, but rather in HB 1293.

I think people who really understood the intention and proper practice of Seattle Design Review are no longer with us. Current practice doesn’t make a very good case for anything, but the principle is good – Seattle has a compelling interest in its built environment, and a board of competent practitioners can hold designers to a much more effective standard than can be written into municipal code.

The projects that fall outside that program’s reach – “a few townhomes” – sure don’t provide a very inspiring example of what architects are going to provide if left to their own devices. That in turn helps build up sentiment against development in general, and it’s hard to say for sure that developers can count on Olympia to keep up the deregulatory policies, especially when deregulation continues to fail to deliver the perpetually promised affordability. Architects have a compelling interest in programs that reward good design in the built environment, where the market clearly can’t be counted on.