In the beginning, August 11, 1950, the first Seattle Seafair celebration was a bang-up success. The summer event was new and everybody involved was an innocent.

White-maned Victor E. Rabel, chosen as Rex I of Seafair, was deemed Founder of the Realm of Neptune. Rabel’s handsome presence could not have been more regal: he was, in fact, dignity with a twinkle in his eye. Years later, Rabel recalled his arrival by boat at the foot of historic Washington Street on the Seattle waterfront. He remembered being saluted by “whistles and sirens filling the air, and a huge crowd — two policemen and two seagulls.”

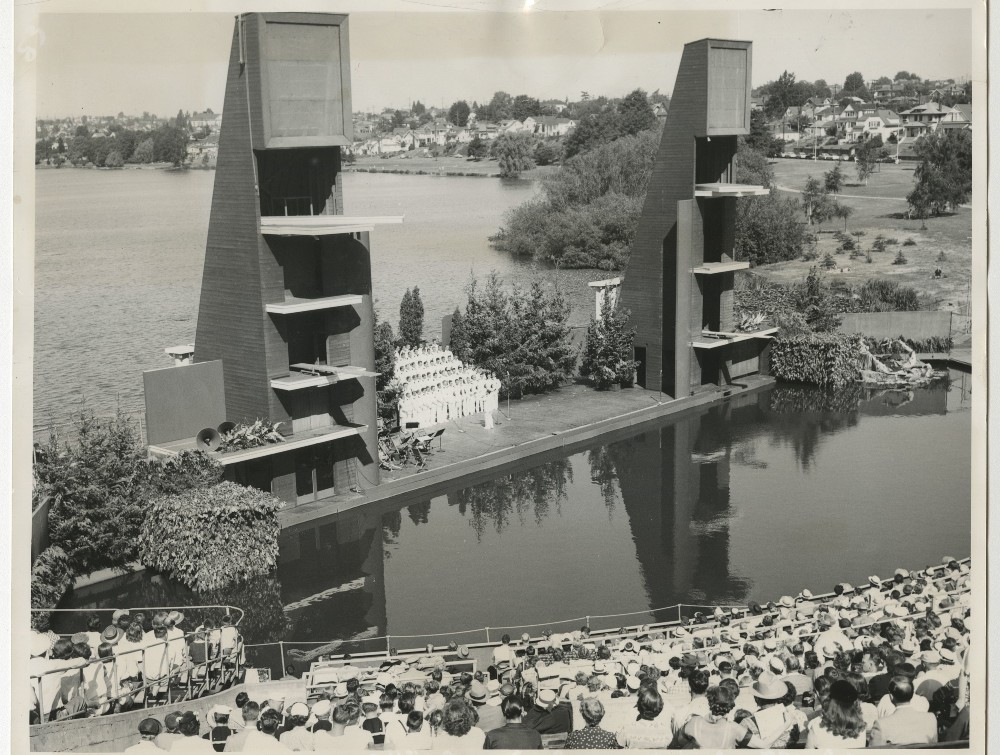

Movie starlet Wanda Hendrix led the first Torchlight Parade; a Pistol Tournament was held; dancing at the (still-standing) Trianon Ballroom was featured; and a “national” water-skiing championship was staged on Green Lake. A special feature, remembered and cherished by many, were the Aqua Follies at the old Aqua Theater on the south shore of Green Lake.

Nothing was broken, no one was hurt, and every hotel room in the city was sold out. People made money, engaged in a long list of sheltered and street events, and generally had fun.

In 1950, hydroplane pioneers Ted Jones and Stan Sayres were tinkering with something called the Slo-Mo-Shun off Sand Point on Lake Washington. The unexpected result was a new world’s record for speed on water. In 1951, Seafair introduced roostertail mania, adopting the hydroplane as its symbol. Thereafter, the lake’s many accessible beaches and a massive log boom (where pleasure boats tied up) were filled with gawkers, party-goers, sunburned limbs, and screaming participants.

A Seafair cult emerged from the feats of the U.S. Navy’s daredevil pilots called “The Blue Angels.” In early days those mostly bronzed fraternity-row heroes were watched from Seattle’s porches and lawns. A Greater Seattle Chamber of Commerce representative boasted that The Blue Angels often flew up-side-down at 10,000 feet elevation.

One August day in the mid-1950s, A.M. “Tex” Johnston, Boeing’s top test pilot, took the prototype 707 “Dash Eighty” out for a spin — literally. Johnston was flying the only commercial jet in the world at the time, and Boeing wanted to show it off to the hydro-race crowds. Tex took a look at the quarter-million spectators around the shimmering lake, slowly eased the giant craft down low, then pulled it up and executed a slow roll. Tex evidently liked the sensation of rolling a 707, because he came around and did it a second time. Boeing executives on the ground were transfixed and apoplectic.

For 16 years the Aqua Follies at Green Lake were a focal point of Seafair. The event consisted of Busby Berkeley-type mermaids and Esther Williams aquabatics, abetted by old-fashioned joke-telling masters of ceremonies, including the occasional presence of Bob Hope and his signature golf club. After 10 years or so the Follies failed to make a profit. Greater Seattle had to trim its sails, so it put the nautical show in drydock, and moved events to the Seattle Center in the Denny Regrade.

The Seafair Pirates’ beach-landings and bellows were at first amusing and unexpected, and many thought their antics were beloved and original. Occasional lapses of judgement, especially related to the Pirates’ sexist treatment of women, were deplored by some observers. For example, when the Pirates’ invaded Portland’s traditional Annual Rose Festival and New Orleans’ Mardi Gras parade, alarming reports made their way back to Seattle. Concerned that the Pirates’ barmy exploits would discourage tourists, Greater Seattle retired the Pirates in 1966. In 1970, on a “try-out” basis, the Pirates were raised from their watery grave and have been rampaging ever since.

Nard Jones, Seattle chronicler and Post-Intelligencer features editor, published a 1970 broadside aimed at Seafair. He wrote in part: “It’s a hick show that has nothing to do with Seattle’s traditions.” With tongue in cheek, Jones recommended that Greater Seattle leaders be strapped into the cockpits of old hydroplanes: “set the throttle wide and aim at the log boom. The crowd would love it.”

In October 2970, Mayor Wes Uhlman called for “sweeping changes,” in Seafair, noting that the event cost Seattle taxpayers over $100,000 and attracted few visitors. Adding to this conversation, Post-Intelligencer columnist and gadfly Emmett Watson anointed himself President of “Lesser Seattle,” the scourge of Pacific Northwest Babbitry. In 1971, the amplitudinous” “Tiny” Butler declared himself King Hex of the “Grosser Seattle Seattle Seafarce Trophy Dash.”

Adding to this conversation, Miss Skunk Bay, sponsored by the Skunk Bay Lighthouse Association, was entered as a Seafair Princess candidate. The candidate, Sharon Jean Demuth, 24, was nominated by PR man Gary Boyker. Demuth claimed she entered the contest to “put some fun and life back into Seafair.” The rules were promptly changed to prevent such entries, dashing the hopes of Miss Skunk Bays everywhere.

Despite changes and challenges, Seafair continues as a Seattle summer celebration. This year, August 4-6, Seafair, including 30 community events, and the participation of 3,000 volunteers, will recognize its 74th year at Genessee Park on Lake Washington. Hydroplanes will be on the water and Blue Angels in the sky.

I was a young, blonde, mini-skirt wearing person during the Pirate’s heyday…They had a “black miriaha” paddy wagon they would cruise around downtown in, in order to “kidnap” young women. I hid in urine soaked alleyways when I spotted them in town. It was that scary for us. Ugly days.

What is the DEI Plan? Without one, Seafair will die!

Lovely days, when Seattle didn’t take itself so damn seriously

It’s Sharon Jean Demuth