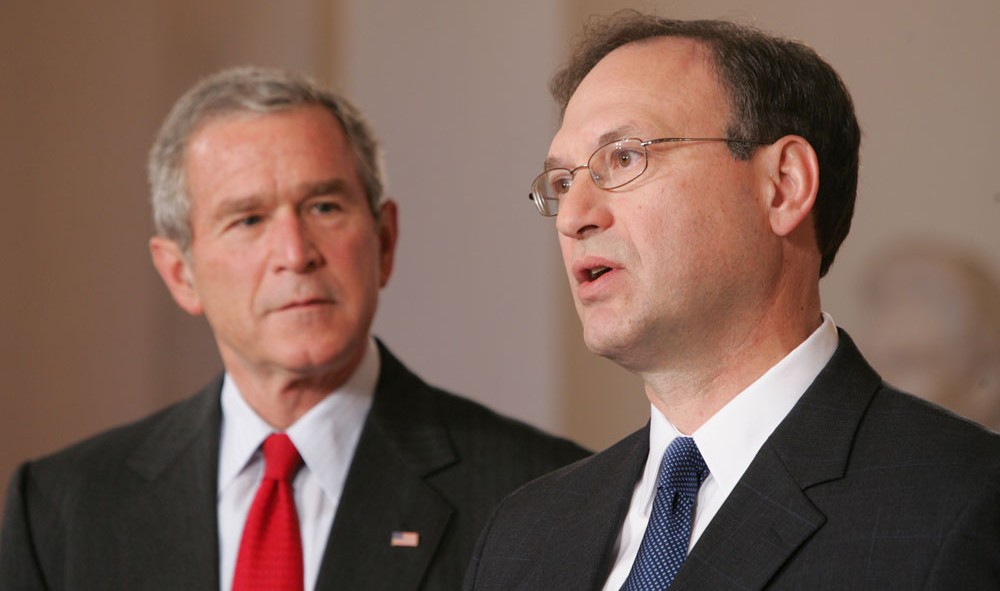

The Biden years have bestowed on one elderly and insular American the unchecked authority and the position to impose his opinions as the law of our land. Not the president, nor any power on Capitol Hill: The power is being exercised by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr.

Alito wrote the high court’s opinion overturning Roe v. Wade taking away the right of American women to control their own bodies. Power over pregnancy has been passed to male-dominated state legislatures. The justice struck again last week, stripping the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency of authority to protect millions of acres of America’s wetlands.

By imposing his own definition of the federal Clean Water Act, enacted 51 years ago under the Nixon Administration, Alito has followed a rule defined by onetime Jersey City political boss Frank Hague: “I am the law.” The justice’s opinion follows, by a year, a Supreme Court opinion – in which Alito concurred – severely limiting the EPA’s authority under the Clean Air Act to limit power plant emissions.

Justice Elena Kagan, dissenting from both opinions, argued that the Supremes’ conservative majority is doing exactly what the political right has charged ever since Brown v. Board of Education – legislating from the bench. “The court will not allow the Clean Water Act to work as Congress intended,” she wrote. “The court, rather than Congress, will decide how much regulation is too much.”

And, referencing the Clean Air Act opinion, Kagan added: “There, the majority’s non-textualism barred the EPA from addressing climate change by curbing power plant emissions in the most effective way. Here, the method prevents the EPA from keeping our country’s waters clean by regulating adjacent wetlands. The vice in both instances is the same: the court’s appointment of itself as the national decision maker in environmental policy.”

The Founders of our nation could not have forecast human-caused warming of our planet, or agricultural chemicals contaminating nearby rivers, or mega-malls paving over wetlands for parking. Nor could they have anticipated the importance of curbing carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, or the importance of wetlands in preventing floods.

The Alito evisceration of the Clean Water Act will likely mirror his Roe v. Wade opinion in that it tosses authority back to the states and may well replicate the same demarcation between blue states and red states. The Red states seem to believe that responsibility for life begins at conception while washing hands beginning at birth.

The opinion was done by design. A couple, Chantell and Michael Sackett, bought land near Idaho’s Priest Lake and began filling in what an appellate court described as “a soggy residential lot.” The EPA ordered them to stop and directed that the land be returned to its original state. The Sacketts sued, and the Supreme Court allowed the lawsuit to proceed.

A right wing legal outfit, the Pacific Legal Foundation – once headed by future Interior Secretary James Watt – latched onto and argued the Sacketts’ case. All nine Supreme Court justices agreed that EPA had overstepped its authority with the Sacketts’ property, but the court majority rejected a narrow decision in favor of setting broad policy.

In his opinion, Alito wrote that federally protected wetlands must be directly adjacent to a “relatively permanent” waterway “connected to traditional interstate navigable waters.” Congress must, he wrote, deploy “exceedingly clear language if it wishes to significantly alter the balance between federal and state power and the power of the government over private property.”

Justice Alito split hairs and inserted his own definition of what is – and is not – covered by the Clean Water Act. The language of the law, speaks of protecting wetlands “adjacent” to “waters of the United States,” is not exceedingly clear, leading Alito and the court majority to opine: “Wetlands that are separate from traditional navigable waters cannot be considered part of those waters, even if they are located nearby.”

If you want to see consequences, just look around. With one opinion, Alito has stripped from protection at least 45 million acres, or as much as half of the country’s wetlands. America is filled with areas that are underwater for a portion or most of the year. Pollution from these wetlands, e.g. PCBs and pesticides, flows into the “Streams, oceans, rivers and lakes” cited by Alito. Our Skagit and Snoqualmie Rivers overflow their banks during late fall and winter storms. Yet, since both rivers flow entirely within the state of Washington, they do not qualify as “interstate navigable waters.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, while agreeing that the Sacketts’ soggy lot was “not covered by the act,” broke with his conservative brethren to argue: “There is a good reason why Congress covered not only adjoining wetlands but also adjacent wetlands. Because of the movement of water between adjacent wetlands and other waters pollutants in wetlands often end up in adjacent rivers, lakes and other waters.”

“This decision is a giveaway to big polluters by stripping the EPA’s ability to protect our health and clean up our water,” Rep. Adam Smith, D-Wash., wrote in reaction to the Alito opinion. Want to see Congress’ “original intent?” The Clean Water Act was a bipartisan response to a major oil spill which contaminated California beaches near Santa Barbara, and when the spark from a passing trail caused the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland to catch fire.

We had plenty examples of polluted water in this Washington. When I was growing up, raw sewage was discharged into Bellingham Bay. The bay’s pulp-mill-polluted waters, the color of tobacco spit, were pictured in Life magazine’s first special issue on the environment. What we didn’t know at the time, the mill operator was also discharging mercury into the bay.

When the Sacketts’ case originally came before the Supremes in 2012, now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that the Clean Water Act required only a that protected wetlands have a “significant nexus” to nearby flowing streams and lakes. The Kennedy interpretation, used as precedent in past CW lawsuits, was tossed out by Alito’s opinion.

Jettisoned, as well, a proposed Biden Administration rule to further protect wetlands. In a statement reacting to Alito’s opinion, President Biden said: “It puts our nation’s wetlands – and the rivers, streams, lakes and ponds connected to them – at risk of pollution and destruction, jeopardizing the sources of clean water that millions of American families, farmers and businesses rely on.”

Justice Alito is not only imposing his will on the law but making the law. The burdens of his decisions must be borne by those who breathe polluted air, drink contaminated water, endure floods and other climate extremes, and/or find themselves expecting unexpectantly.

Supreme Court decisions have consequences in all of our lives.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Then you Joel for a helpful overview of a bad decision by Alito and SCOTUS majority. By tossing out 45 years of consistent practice by federal agencies as authorized by Congress, Alito may have unleashed havoc on developers who attempt to pollute Alito’s “non regulated wetlands”. The CWA allows citizens take action against polluters. Well funded environmental organizations, no longer fettered by EPA and Corp of Engineers permit processes can have an open season on developers who fail to at least assess whether the wetlands they intend to pollute are “Waters of the US” per Alito’s vague reasoning. Dueling hydrogeologists will offer conflicting testimony in front of weary Federal judges. This will be costly for developers who may be feeling like they won one over the pesky EPA and environmentalists. With NO agency rules in place on how to implement Alito’s vague definition Developers may want to be careful. They could be held liable for polluting the water supplies of downstream communities. Destroying the favorite duck habitat of their friends may also catch up to them.

As for Washington State wetlands we have our own state clean water act and the Waters of Washington include a broad definition of wetlands. We got WOW and it beats the current SCOTUS WOTUS.

Joel- No doubt left about how you feel!

SCOTUS is eroding the Chevron holding that leaves to administrative agencies with “expertise” the authority to interpret “ambiguous” statutory language. Its ambiguous because Congress wanted to “do something” but couldn’t agree on how to define key language. Chevron was a companion case to the Court’s upholding BPA’s “DSI” Regional Act contracts, which also has very broad language.

EPA took a very broad view of its authority. So did BPA. Maybe justifiable, maybe not. Both agencies broad interpretations have since been cut back. Today, perhaps neither the Clean Water Act or the Northwest Power Act might become law, certainly as originally enacted. They were “of their time.”

Bottom line: Its back to Congress to legislate clear intent, or to the administrative agencies to adjust to a changed SCOTUS and political environment.

I read the Alito’s decision, and a bit of Thomas’s concurrence (that of course wants to go much further and limit regulation only to water that is functionally, commercially, navigable, and only then to regulate the removal of obstructions to that navigation; sheesh!). I noted Alito’s immature churlishness on display, in sarcastic passages inappropriate, imo, to a SCt opinion (Alito clearly thinks he’s carrying on the literary tradition of Scalia, a bar Alito falls far short of, having neither the brains, the (any!) sense of humor, or writing ability of Scalia). I also note that I too wish to protect water everywhere to the fullest extent possible, for their ecological and other values. I understand, as anyone that can see or read or think should understand, that waters are connected to each other in a myriad of different ways, and that aspect must be recognized in their regulation (best available science!).

All that said, I did not read the opinion as something beyond the pale of legal analysis. Yes, Alito/the Court could’ve kept the opinion narrow, and just ruled that the Sackets could build their house and that their property was too attenuated to justify CWA regulation. And yes, Alito’s frequent references to the fact that the CWA covers way to high a percentage of the country’s waters, takes away from State’s Rights, and unreasonably limits commercial activity were all gratuitous, misleading and subjective statements that made the decision look like a policy doc than a legal opinion. But, I thought that the central issue had merit; the central issue being a need to more definitively identify the scope of what qualifies as waters of the U.S. for regulatory purposes. If Congress had done this, there would not have been the skein of court decisions over the last 50 years. We cite Kennedy’s “significant nexus” test as a good test because we like the discretion it bestows to the agency and the more expansive scope it allows. But like the new Adjacency Rule in Sackett, Significant Nexus is still just an opinion and not a clear rule or guidance laid out by Congress. Administrative employees at the level of implementation will, in the world of either rule, exercise discretion in ways that are good and bad, too much or too little, as befits the employee and the regulatory (bureaucracy) that they learn to work within (power corrupts at all levels). Any decision by an administrative employee that skews too far one way or the other will gore someone’s ox, leading to litigation or resentment to the scheme. Call it regulatory abuse, call it consequential government actions by unelected officials; whatever. Without clearer guidance/rules, abuses will happen.

All of which is to say, that 90 years into the Administrative State ushered in by the New Deal, it makes sense to me that agencies and rules have likely reached a point where they need serious pruning. The state of scientific knowledge of the connectedness of nature has certainly reached the point where Congress could amend the CWA to specifically and clearly authorize the regulation of waters to the extent that even Kavanaugh will be happy. Why shouldn’t, under our system of government, we expect Congress to go ahead and do that, for the CWA and a host of other regulatory statutes? True, Congress has a tough time these days with these issues, but that, to me, doesn’t mean that the need is not there. Without Congressional reformatory actions, we are facing case after case where the radical, activist, current court will do the pruning of the administrative state as they see fit. And I doubt I will like that fit.

Agreed: “it makes sense to me that agencies and rules have likely reached a point where they need serious pruning. …..”