By all measurements, Dr. Tom Hornbein should have died 60 years ago when he and Willi Unsoeld reached the summit of Mt. Everest via its West Ridge in late afternoon and were forced to bivouac atop the world at 27,900 feet.

But the Jet Stream, responsible for the great plume off the summit of Everest, for once stayed silent. “That night (there) was not any wind: Had there been, we would not be having this conversation,” Hornbein told me years later.

The two climbers descended to the South Col, completing the first traverse of Everest. “This audacious feat has perhaps yet to find an equal in the annals of Himalayan climbing,” the American Alpine Club said in an appreciation Monday. Unsoeld was to lose nine of ten toes and featured their removal in slide shows on the climb.

Hornbein lived to be 92, and died Saturday at his home in Estes Park, Colorado, in the shadow of Longs Peak, where a 13-year-old boy from St. Louis, at summer camp, first set sight on high places. He and wife Kathy had moved back to Colorado after a lengthy career that included 16 years as chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Washington Medical School.

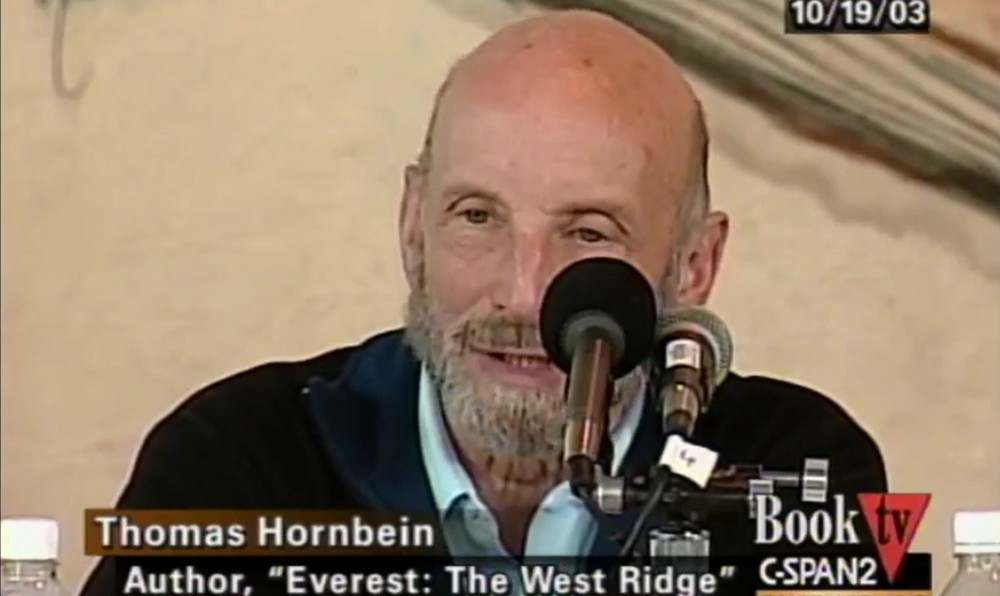

“I discovered mountains: It was the biggest, most pivotal event of my life,” he would say. “Mountains proceeded to direct everything I did in my life.” Reflecting on her husband’s life, Kathy Hornbein observed: “It (Colorado) was his soul place: Everything he did in his life was influenced by that experience.” As Hornbein lay dying, family propped him up in bed so he could see Longs Peak out the bedroom window. Hornbein’s book, Everest: The West Ridge, has come out in multiple editions, each with a new preface, each relating what became of his climbing companions. It is a classic of mountaineering literature.

Hornbein was renowned as a climber, a medical researcher, and a friend. In words of physicist and fellow climber Bill Sumner, he had a knack for “being there for life decisions. Tom held my son, Sasha, before I did. He was there, in a surgical mask, handing me my baby.” Thirty years later, on Hornbein’s 80th birthday, he was out climbing with Sasha.

In turn, Hornbein organized a climb of The Tooth above Snoqualmie Pass to mark the 80th birthday of his friend and late-in-life rock climber Stim Bullitt. “Tom was a wonderful person in every way. He often talked of facing death as a celebration with good friends,” Tina Bullitt, Stim’s widow, wrote in a note informing a friend of his death.

The 1963 American expedition to Mt. Everest was designed with two goals. The first was to put the first climber from the United States on the 29,028-foot-high summit. The Brits had first climbed Everest a decade earlier. Nowadays, hundreds climb each year via the South Col route, with ropes fixed in place and photos of lineups at the Hillary Step. It was far different in 1963.

The second goal, first in the heart of climbers in the expedition, was to pioneer a new route to the summit. “The real climb would be the new route,” Unsoeld’s widow, former U.S. Rep. Jolene Unsoeld, said years later. Hornbein had seen an aerial shot of Everest taken by the Indian Air Force. He studied the West Ridge and saw a narrow couloir that offered possibilities.

The first objective was achieved when Jim Whittaker summited via the South Col route. Hornbein and Unsoeld were set free, with limited resources, to try the West Ridge. The two men had met and bonded during Americans’ first ascent of Masherbrum, a strikingly beautiful 25,566-foot summit in the Karakoram, remotely in far reaches of Kashmir.

“We weren’t seeking risk but – to be truthful – risk is uncertainty,” Hornbein said years later. The ascent proved difficult and technical. One difficult stretch still bears the name Hornbein’s Couloir, informally nicknamed Hornbein’s Avalanche Chute. Around and beneath them were three more 8,000 meter peaks – Makalu, Lhotse, and Cho Oyu.

In Everest: The West Ridge, Hornbein described nearing the summit: “Completely alone, range upon range I gazed westward. Beneath me clouds drifted over Lho La (pass), chasing their shadows across the flat of the Rongbuk Glacier. I remembered afternoons of my childhood, when I watched the changing shapes of clouds against a deep blue sky, sensing elephants and horses and soft mountains. On this lonely ridge I was part of all I saw: a single feeble heartbeat in the span of time, and the space above me.”

The two climbers summited in late afternoon. How to get back down? “It’s too damned tough to go back (via the West Ridge): It would be too dangerous,” Hornbein told Whittaker, by then back at base camp, on the radio. So, the two men started down the South Col route, catching up with Lute Jerstad and Barry Bishop, who had climbed that route earlier in the day. The four men experienced history’s highest bivouac. Hornbein suffered no physical injury.

Accounts of mountaineering have, over the years, taken on a me-centric tone with tales of rivalries and discontent among climbers. (The first climb of K2, the world’s second highest summit, saw a later lawsuit.) Not so Hornbein’s book, several times updated as the sport has evolved. “My experience was doing something I love to do,” he explained to me. “This was simply a bigger mountain to which was attached more notoriety. I wanted to show a small group of people working together, solving problems through daily interactions. I wanted to make it real.”

“We were married a few years when I asked him, ‘What was the best thing about Everest?’ He replied simply, ‘the friendships,’” said Kathy Hornbein.

Willi Unsoeld would die 16 years later when an avalanche struck a party of his students from The Evergreen State College on a climb of Mt. Rainier. “Tom continues, every year, calling me on the anniversary of the climb,” said Jolene Unsoeld, who died 18 months ago. With the advent of cell phones, Hornbein was able on occasion to call her from high places and describe his experiences.

Looking back on Hornbein’s life, American Alpine Club president Graham Zimmerman reflected: “Tom Hornbein inspired us to dream big, fiercely pursuing those dreams, and be exceptionally kind on the journey.”

Such is a life well lived.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A wonderful tribute, Joel . Tom was also an exceptional medical faculty leader. His ego never entered into discussions of complex issues; he had already been to “the top of the mountain.”