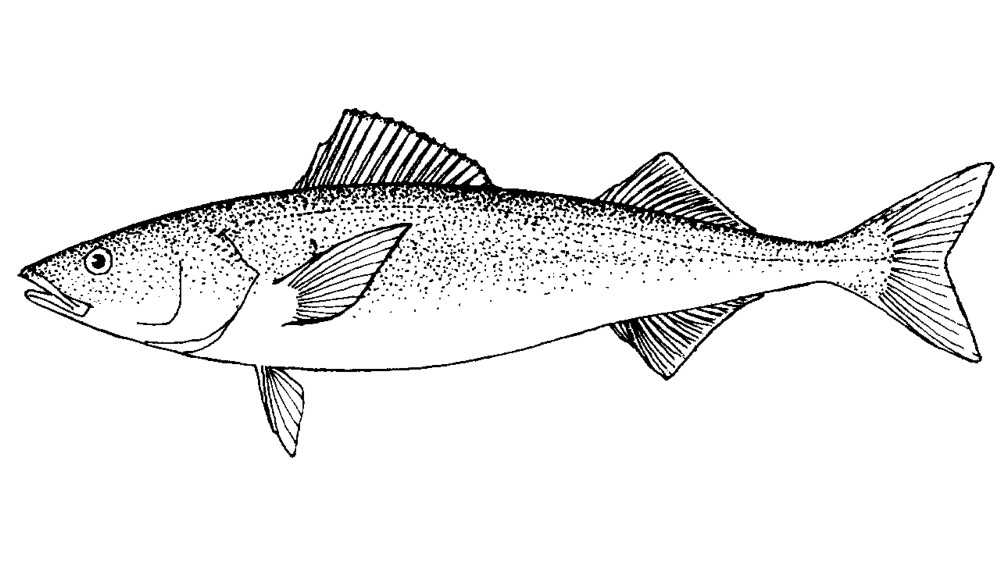

Most Americans don’t know black cod, also called sablefish, and in Hawaii, butterfish. The Japanese know it, and for decades have paid top dollar for its white, flaky flesh. Like Copper River salmon, black cod is high in fish oil (and calories). Comparing black cod to Japan’s famous high-fat, high-dollar beef, a local marketer calls it “the wagyu of the ocean” — “a premium white fish known for its large petal-like flakes as much as its rich, buttery flavor.”

At fish markets, fresh black cod caught in season (mid-March through November) usually goes for more than $20 a pound. If smoked, it can be double that. In Seattle, a few restaurants have it: Manolin, Local Tide, Sushi Kasiba and some others. Ray’s Boathouse has a black cod entrée at $52 a plate. At Canlis, black cod is part of a $175 multi-course feast.

Until recently, all black cod has been caught in the ocean. The fish is a long-lived species; many hauled up in longlines or pots are 40 years old, and some can be decades older. The length of generations limits the annual allowable catch — and the catch has been gradually falling. In the years 2017-2021, it was down 20 percent from a decade earlier.

The U.S. research work on black cod is based at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center’s Manchester Research Station in Kitsap County. Penny Swanson, who has worked at the Center for more than 30 years and is now director of its Environmental and Fisheries Science Division, says, “I’m proud of what scientists have done here.” The question now, she says, is not whether black cod aquaculture can be done, but “the willingness of society and government” to allow it. Salt-water fish farming has its opponents. One of them is the state Commissioner of Public Lands, Hilary Franz, who has recently shut down steelhead farming in Puget Sound, citing environmental effects.

“All agriculture has environmental effects,” Swanson says. “Our role is to provide the research to minimize those effects.”

Swanson is a federal employee. The Northwest Fisheries Science Center is part of NOAA — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which in turn is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. NOAA has long believed in fish farming, partly for economic reasons — to create a new industry for Americans — and also for environmental reasons.

The environmental argument for fish farming is that it expands the food supply for humans without increasing pressure on wild fish. The world has ever more people; it does not have more wild fish. In 2021, 80 percent of the salmon produced worldwide was farmed. In the United States, around two-thirds of salmon consumed is farmed — almost all of it imported. The largest share comes from Norway, a country known to be environmentally conscious.

Salmon and trout are easier to grow in captivity than black cod, and people have long since learned how to do it. In the wild, salmon spawn in a few inches of fresh water. Their eggs are relatively large, as are the hatchlings. The life of black cod in the wild is not so easy to mimic in a hatchery. Black cod spawn in the deep ocean, where it is cold and dark. Their eggs — about one-fifth the diameter of sockeye salmon eggs — produce tiny larvae that feed on microscopic organisms.

In the wild, black cod females may not spawn until they are nine years old. At Manchester, scientists have been using wild-caught fish already old enough to spawn. To domesticate the species — which has long since been done with salmon, and most other species of farmed animals — the biologists will have to breed fish that have been raised in tanks. That’s the last step.

The Manchester research station is NOAA’s largest “wet lab” in the United States and the only one working on black cod. Researchers there have already shortened the time it takes for a fertilized egg to grow into a market-sized fish. They begin by fertilizing black cod eggs in vitro. The sperm is from a “neomale” — a male fish that can produce all female offspring. The females grow faster than the males, making them worth more in the market.

In the wet lab, the fertilized black cod eggs are put in tanks with salt-enhanced water at about 38 degrees Fahrenheit and kept in the dark for 50 days. When they are moved to other tanks the hatchlings look like eyelashes — 100,000 wiggling eyelashes in a tank of saltwater, cloudy with clay and algae. The water is slowly warmed. When the juvenile fish reach a quarter to half a pound in weight, they are moved to NOAA’s research net pens at Manchester and are fed small brown pellets — salmon food. The fish are also injected with a vaccine to prevent furunculosis, a disease that can be lethal to juvenile fish.

Pen-raised black cod reach harvest size, 5 pounds, in another 13 months. Researchers have shortened the whole process from egg to marketable fish from five-to-six years in the wild to two years. “We think we can shorten it even more,” Swanson says.

Ken Cain, former professor of aquaculture at the University of Idaho, is the manager of aquaculture research at the Manchester labs. He says of black cod aquaculture, “I think it’s ready to take off.”

The United States imports almost all the farmed salmon that Americans eat, having conceded that industry to Norway, Chile, and Canada. With black cod — a fish not native to either Norway or Chile — Canada has been the leader. Biologists there have reduced the time from birth to spawning from nine years to four. British Columbia-based Golden Eagle Sablefish, which has its net pens in a remote cove in Kyuquot Sound on the northwestern coast of Vancouver Island, is up and running. Its distributor here is Wheeler Seafood, based in Puyallup.

In the United States, if NOAA can also shrink the spawning cycle to four years, and not depend on wild-caught adults to produce fingerlings, it will have shrunk the time from birth to spawning to the raising of new generation from a combined 14-15 years to 6 — a huge achievement.

If the seafood industry is to take advantage of NOAA’s 20 years of work, the first company will likely be Sequim-based Jamestown Seafood, which has been raising oysters and geoduck in Sequim Bay. Jamestown would like to begin raising black cod along with steelhead at an established commercial net-pen site at Port Angeles harbor. Because the company is owned entirely by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, it has asserted in a lawsuit that Hilary Franz’s order shutting down net pens in state waters impinges on its tribal rights. The matter has not been settled.

The tribe claims that its treaty rights to harvest fish in the wild is of little value, because it has no fishery off the northern Olympic Peninsula. “There’s nothing left,” says Jamestown Seafood CEO Jim Parsons. “We might as well grow it.”

Parsons, an industry man with a background in trout rearing and salmon farming, recalls traveling with Jamestown S’Klallam’s chairman, Ron Allen, to see salmon farming in New Brunswick province, Canada. The men were impressed with the jobs created in the community there. A commercial fish farm at Port Angeles would give tribal members job opportunities in addition to work at Jamestown’s casino. It would also give Americans a stake in a new industry, creating a premium seafood item for export rather than conceding it to others.

For Jamestown Seafood, the work this year includes testing the marketplace with 15,000 to 20,000 pen-raised black cod from the research project with NOAA at Manchester. The tribal company has placed fish with New York sushi chefs, who, says Parsons, praise it highly. Jamestown’s local distributor, Key City Fish in Port Townsend, is approaching fish markets in the Puget Sound area.

Marketing government-raised fish is a short-term arrangement. The goal has been to work out how to breed them and grow them, to minimize the environmental impacts and maximize the value. At NOAA, Penny Swanson says the government aims to transfer the technology — all of it, from spawning to harvest — to the private sector without further subsidy. The investors who take it on have to have enough capital. They have to know the costs per pound of fish and what they can get for it. And they have to know that they’ll have official permission to do it.

“We don’t really know all that yet,” Parsons says. “It’s early.” It’s clear enough, though, that pen-raised black cod will become a part of the global seafood industry. The question is whether it will be done in Washington state or somewhere else.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Bruce, You have left out the Tribe’s well publicized partnership with Cooke Aquaculture. With disastrous results, Cooke has repeatedly mismanaged their own Washington net pen operations and now seeks legal cover through a deal with the Jamestown S’Klallam. “Closed system” aquaculture on dry land shows great promise as a sustainable and safe way to supply marketable seafood. Net pens remain an environmental threat, wherever they are located.

Right – net pens are open water feed lots, whoever runs them. If black cod isn’t miraculously less problematic, we’ll be “conceding” that business to other countries as well.