I first tuned into Martin Gurri via a podcast, after which I read his amazing book, The Revolt of the Public. Gurri shows how everything changed with the internet’s “tsunami of information,” toppling elites and powering the public (really, though, that is plural, “publics.”)

Gurri’s thinking isn’t ideological or predictable. If you only want to hear from or read people that confirm what you and your tribe think, don’t bother with him. If you’re interested in an analysis of where we find ourselves and the forces that are shaping us, check out Gurri’s work.

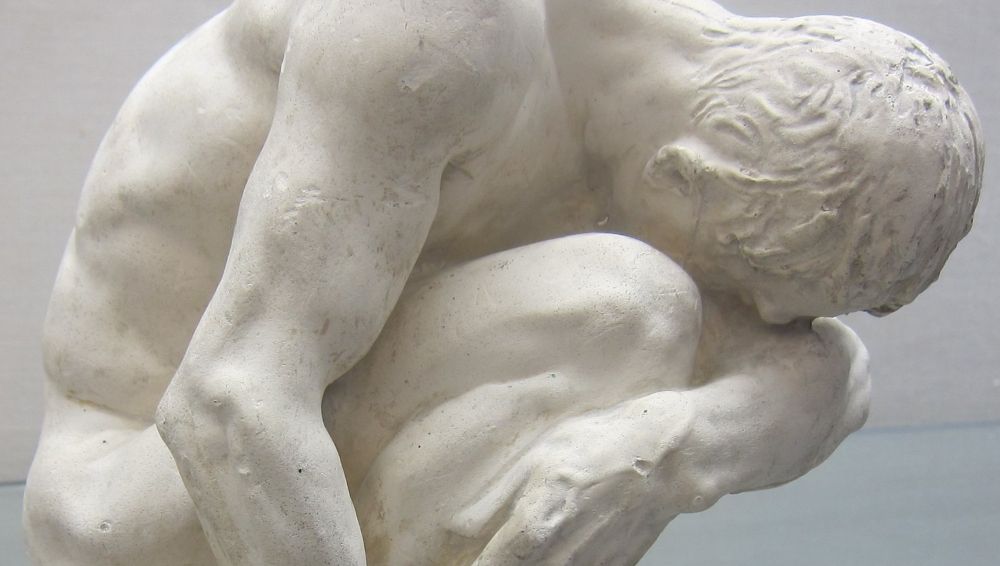

Gurri has a recent essay at The Free Press in which he argues that abundance isn’t the answer to the problem of the human condition. Adventure is. But, a spirit of adventure, of risk-taking, or innovation — is being submerged in decadence. “We trumpet our splendid virtues but live in a defensive crouch.”

We’re all dressed up with no place to go. We are cowering before the future rather than plunging into it. Here’s Gurri:

” . . . our attitudes about the future are rapidly shifting from confidence to dread. When we look ahead, we perceive a sea of troubles: ecological apocalypse, eternal pandemic, political and economic mayhem. Our vision stops at the smartphone. In a recent poll, 56 percent of respondents said the government should favor safety over innovation. The sense of adventure has curdled into fear.”

Gurri is on-target about “abundance” because a bunch of liberal commentators and economists have been arguing that nation requires, and the Democrats need to champion, an “abundance agenda.” More of all the good stuff — doctors, health care, nurses, teachers, buses, ex’s, homes, etc. Supply-side Progressivism, is one term for the “Abundance Agenda.”

Gurri isn’t so sure “more,” even of such “good stuff,” is the answer. (Remember the slogan emblazoned on the trucks of one of the big-box stores, “More of Everything”?) We already have wealth and leisure. Yes, unevenly spread, but compared to the lives of human beings throughout history and in some parts of the world today, we got abundance. What we lack, says Gurri, is adventure, a sense of the possibilities, of what is asked of us. Gurri continues,

‘Having lost faith in growth and progress, we insist on rules that allow us to cling to what we have, even at the expense of those who have less. From the NIMBY movement to the constant cries of ‘a million species on the brink of extinction,’ we wish, like Faust, to freeze the moment, to hit the pause button on the world-historical drama and so be preserved against the holocausts to come. We trumpet our splendid virtues but live in a defensive crouch. Change along any dimension we assume will involve loss and pain.

“But if we throttle risk and adventure, the prophecies of disaster become self-fulfilling. The democracies of the world, managed by elites who have bought into the doomsday creed, are in fact stuck in a rut. The French economy has flatlined for 15 years; as I write this, the protected classes are throwing a tantrum in the streets of Paris, demanding not liberty or equality but the right to retire at 62. Italy hasn’t grown in this century. Japan has stagnated for a generation and more. Britain, after an impulsive divorce from the European Union, has spiraled into negative territory.”

Is Gurri onto something? Do we increasingly dread the future and, like Faust, wish “to freeze the moment”? “After we get in, close the gates!” Gurri is arguing that human beings are built for meaning, for purpose, for something bigger than themselves. Consider how energized people typically are in the event of some emergency — a storm, flood, or fire. Something that requires all hands on deck and pulling in the same direction?

Wealth and leisure may sound good — certainly did when most human beings had almost nothing and worked constantly to keep even that. But having attained them, is this all there is? Are we left with “The White Lotus,” a celebrated close-up of how self-obsessed and cruel really, really rich people can be. If the answer isn’t “More of Everything,” then we’re not up against an economic policy problem, but something different. So Gurri, asks “Is it possible to cure a culture? ” His answer:

“No cure, let me suggest, can be obtained by tooling around with economic policy. None will be found by increasing or redistributing the wealth of an already bountiful nation. These moves might treat the pain but not the wound. The task of renovation must be conducted where culture itself abides: that is, within the heart of every American. An epidemic can only be stopped one patient at a time. Progress will necessarily be slow, unsteady, and full of baffling episodes.

“We aren’t looking for self-actualization but self-transcendence. Culture is the mysterious way we bond to one another—husband to wife, parents to children, neighbor to neighbor, citizen to citizen. Each of us must discover the adventure that is a human life—the epic adventures of high risk and innovation but also the everyday adventures of love and marriage, of family, of childhood innocence, of being young in a land where the future is a wide frontier. Each of us must learn again to judge right from wrong, health from sickness, and support, with our money but above all with our attention, politicians, artists, and entertainers who embody with integrity the life-enhancing sense of adventure. That is in our power.”

“Self-actualization” was what the influential psychologist Abraham Maslow taught us, as the post-war era of affluence dawned, as the pinnacle of the “pyramid of human needs.” One might ask the Dr. Phil question, “How’s that working out for you?” Gurri, along with the collected wisdom of much of humanity, suggests another possibility, that “self-transcendence” is our real need.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.