An American newscaster announced that Russian forces had been illegally occupying five Ukrainian oblasts (provinces) along the country’s eastern border and southern coast since 2014: Luhansk, Donetzk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and the Crimea. The word “illegally” conceals a lot of history and confusion about this region. Time for a reality check.

For starters, Crimea has been claimed by Russia since Vladimir the Great, King of the Kievan Rus, was baptized in Sevastopol in 988, and all these provinces have had Russian-majority populations for centuries. Accordingly, Vladimir Putin claims Ukraine is not a real state but a part of Russia under Ukrainian nationalist/fascist control that threatens Russians with genocide. Let’s unpack those Putin claims and the history that lies behind them.

This bloody and dangerous dispute between Russia and Ukraine has a long history, one whose depth and detail are unknown to most Americans and many American policy makers. They cheer the deaths of Russian soldiers and rub their hands in anticipation of Russia’s disintegration. Many Americans cheer them on, ignoring the bloody parallels in our own history.

Back to deep history. In the 980s, Vladimir the Great made Kievan Rus the largest state in Europe, stretching between the White and Black Seas. Its people were an amalgam of Norse, Finns, and Eastern Slavs—Rus, but not yet Russian. They vied with other powers: Byzantium, Persia, Mongol, and Turkic peoples to dominate Oukraini (“Outskirts”) open country south of forested land and home to marauding nomads that had dominated the Eurasian steppe since the bronze age.

The growth of Poland and Lithuania in the north and the Bulgarian Empire in the southwest challenged Vladimir’s successors. Beginning in 1223, the Mongols devastated Kievan Rus, burning its capital, Kiev. Western Rus resisted, but the Golden Horde dominated eastern vassals until the Principality of Moscow threw off the “Mongol Yoke” in 1480. In the traumatic interim, the Eastern Slavs evolved into Belarussians, Ukrainians, and Great Russians. In their territories, nomads carried out annual slave raids that depopulated the area. Called the “Harvest of the Steppe,” some 3 million Slavic captives were sold to Byzantine and Venetian merchants who gave us the word, “slave.”

After Kievan Rus disintegrated, the Russian Principality of Moscow became a leading power under its Tsars. But even after the Mongols, Russia and its outskirts suffered devastating invasions by Poland, Lithuania, and Sweden.

Americans may better grasp this violent history by examining that of the American South and West. For example, Russia’s southern expansion and colonization took place as Conquistadors carried out entradas into North America. In 1513 Ponce de Leon reached Florida. Hernando De Soto followed, and soon disease and subsequent Spanish, French, and British raids depopulated the area.

Before our Revolution, France and Spain vied with Great Britain for control of the North American interior and its powerful Indian nations. Similarly, in the Eurasian steppe the Rus played off the equestrian Pechenegs, Polovtsi, (celebrated in Borodin’s opera, Prince Igor), Cumans, and Cossacks against one another for protection.

At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, Tsar Peter I (the Great) overcame Russia’s isolation in an increasingly maritime world by defeating Sweden to gain access to the Baltic, founding St. Petersburg in 1703. Successor Catherine the Great turned toward the warm Black Sea ports.

The storied antiquity of the Black Sea’s north coast echoes in its cities’ names: “Odessa” from Odysseus, “Kherson,” from the Tauric Chersonese, recalling Heracles plowing the hilly peninsula (“Cremi”—hills) Crimea, with the great ox, Taurus. The long Arabat spit on the Sea of Azov’s west shore is called Achilles’ Racetrack.

Russians occupied and rebuilt ancient communities along the Black Sea littoral as British and Americans transformed coastal American Indian and Spanish/French communities into Charleston, Savannah, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans. American settlers migrated into Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi–the “Old Southwest” – just as Russian settlers packed belongings in wagons and headed west to desolated “Wild Lands,” now eastern and southern Ukraine, in the late 1700s. The Wild Lands became “New Lands,” Novorossiya, “New Russia.” In War and Peace, Tolstoy describes these pioneers heading west for a better life.

American colonists and frontiersmen organized short-lived garrison states on the South’s littoral: the colony of Georgia (1732), the multi-racial state of Muskogee (1799), West Florida (1810), the Republic of Florida (1820), and Texas (1837), where the Alamo stands as the most famous garrison site. These garrisons resemble Cossack (the word is a variant of Kazakh, “adventurer—nomad”) communities made up of escaped Slavic serfs and nomads that gathered into democratic garrison states administered from palisaded sichs (forts) by hetmans (chiefs).

The period of Cossack dominance – from the 17th century to Catherine’s seizure of the Zaporizhzhian Cossack fort, Tomakivska, in 1775 – lasted far longer than the ephemeral American republics. They also had greater impact on Ukrainian and Russian history. We barely remember the Southern phantom-garrisons, but Vladimir Putin recruits Zaporozhzhian (“Beyond the rapids” of the Dnieper River) Cossacks into’ his personal guard. Ukraine’s great 17th century unifying figure, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, fought for independence against Poland and Lithuania, and showed deference to ally Russia by using the name Maleky Rus, “Little Russia,’ to identify his country.

In subsequent wars Catherine took all of Ukraine, which, despite violent rebellions, remained part of Russia until 1989. The parallel is in the 1840s, when the United States seized Mexico’s northern half and reached the Pacific. Soon, armed resistance to Anglo land-seizures by “White Cap” Hispanos forced change in New Mexico, and native warfare exploded throughout the West, even in Seattle.

Vladimir made Orthodox Christianity in Kievan Rus subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople. In 1710, Pylip Orlyp, Hetman of defiant Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, issued one of the earliest constitutions of the modern world, making Eastern Orthodoxy the religion of the free Cossack nation, and dividing its government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches (before the writings of Montesquieu), with an independent parliament limiting the powers of the hetmanate. It also banned Judaism. Later, the constitution was suppressed and Tsar Peter placed the Kievan church under the authority of Moscow’s Patriarch where it remained until 2018.

To control ethnic groups, Tsarist Russia promoted Russification throughout its empire, making Russian the language of state, higher learning and publication as well as making the Russian Orthodox Church the state religion.

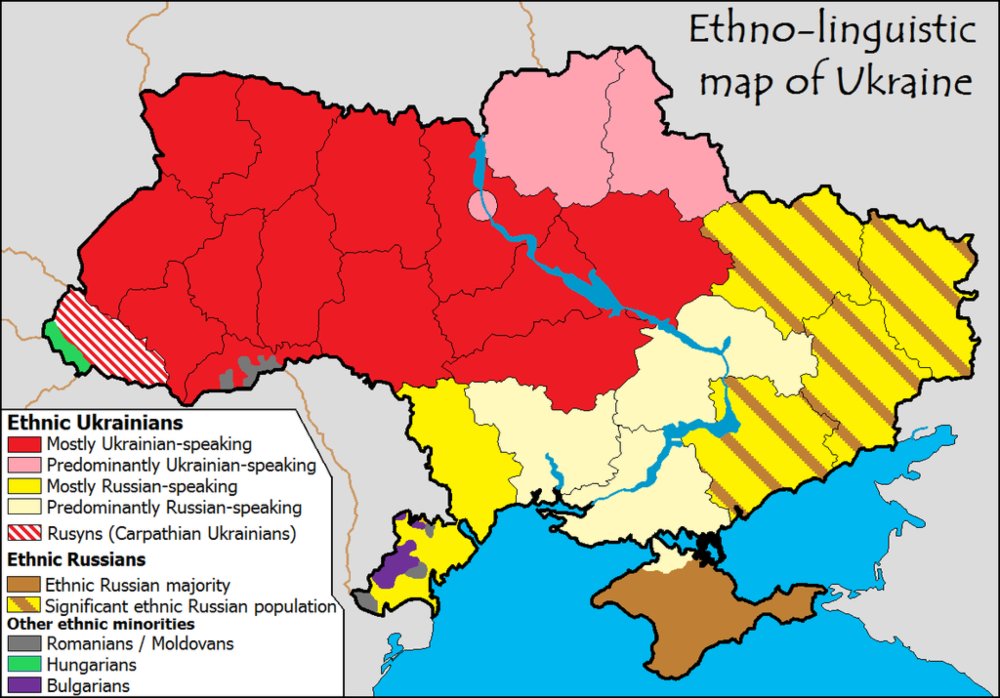

After the death of Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1657, Poland expanded into land west of the Dnieper River that divides Ukraine in a long, lazy S, as Russia did east of it, deploying populations to their advantage and dividing Ukraine into areas of Ukrainian and Russian language majority populations. Toward the end of the 1700s, Austria, Russia, and Prussia partitioned Poland, erasing it as an independent state until 1918. In areas of Ukraine once under Polish rule, Uniate congregations loyal to the Roman Pope faced persecution.

Meanwhile, in North America with the defeat of Mexico in 1848, San Diego, Monterey, Yerba Buena (San Francisco), and Los Angeles filled with Americans prospectors and entrepreneurs, cementing economic and political relations with the East Coast. English became the language of government, education, and publication. It was not until 1870 that New Mexico permitted Spanish to be taught in public schools, but federal policy forbade native languages to be spoken in schools, punishing those who persisted.

Such efforts are now regarded as examples of cultural genocide. Religious persecutions of African-American churches, Mormons, Catholics, and Jews led by Anglo-Protestant elites were common nationwide. During and after the American Civil War, the North crushed the South and buried native resistance in the West, leaving the South and native tribes devastated for nearly a century.

Russia continued to suffer foreign invasions. In 1812 Napoleon advanced to Moscow, his army bringing mass death and famine in its wake. In the 1850s, the Crimea was invaded by France, England, and the Ottoman Empire, causing immense suffering. In 1914 German armies invaded. The October 1918 Bolshevik Revolution toppled the Tsar, and the Russian Empire collapsed in turmoil. At the Treaty of Brest Litovsk, the Central Powers forced the new Russian Bolshevik regime to cede Ukraine. Even when Germany and its allies were defeated in World War I, Ukraine received no respite as White (monarchist), Red (Bolshevik) and Green (Ukrainian) armies fought a brutal civil war.

That warfare ceased with the triumph of the authoritarian socialist government in Moscow. Initially, the Soviet Union encouraged ethnic minorities to speak and be heard in their own languages, but Stalin feared a backlash if terrible truths were revealed. Once again Russian became the enforced official language. An immense system of forced labor camps, the Gulag, was organized to eliminate critics and work millions to death.

The bloodshed intensified as independent Ukrainian peasants—Kulaks—were murdered in the name of collectivization. Forced grain export ordered by Moscow led to famine that killed millions. Ukraine’s population of 30 million in 1915, dropped to 27 million in 1933, rebounded to 30 million in 1940, and dropped again to 27 million in 1945. To escape slaughter or for reasons of ambition, some joined Nazis in murdering 870,000 Jews. Among the most ambitious was Ukrainian anti-Russian Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera.

After World War II, the United States boomed as the postwar Soviet Union struggled to restore industry and rebuild shattered cities. Ukraine’s population rose to 52 million by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Today, its 41 million reflects the millions fleeing war’s destruction.

Since declaring independence in 1991, Ukraine has elected presidents and parliaments that have (with the exception of its elected fourth President Victor Yanukovich, whose pro-Russian moves led to the Maidan protests of 2014) pushed for independence and closer ties to Europe. This has led to violence between Ukrainian and Russian language populations, and ultimately war with Russia.

It is not difficult to understand why Ukraine would seek freedom from Russian domination. But Russia’s refusal to let go of Ukraine and its Russian-majority provinces can also be understood. One factor: Russian memory remains raw of brutal invasions from Europe, leading to the breakup of the Soviet Union. That breakup increased corruption, poverty, and economic disparity among its 46 oblasts and 26 autonomous ethnic republics and regions.

The United States’ aggressive military history, immense economic power and technical prowess have always given the Soviet Union and modern Russia nightmares. Added to that are relentless American commercial and diplomatic efforts and NATO’s increasingly aggressive strategy. These Western forces crippled the 1980s Soviet adventure in Afghanistan, invaded and reshaped the Balkans in the 1990s, invaded Afghanistan, Libya, and Iraq. This adds up to a dire existential threat to a multi-ethnic union that has seen its population halved during the last 30 years. It is said that Putin obsessively watches film footage of Libya’s ex-leader, Muamar Gaddafi’s lynching by his people.

Lastly, consider this parallel history. What if American society continues to polarize? What if the Hispanic population in the American West concludes that they would have done better if northern Mexico had not been conquered? What if Mexico agrees? And what if China, seeing a fragmented U.S. as a plus, chose to provide economic and military support to this end?

Seemingly learning nothing from its experience of Russification, Ukraine’s Parliament passed the State Language Law in 2019, making Ukrainian the mandatory language of government, education, and media. Allowances are made for the languages of Crimean Tatars and of the European Union. But Russian is permitted only in private conversations and church services.

On January 1, 2023, the Ukrainian parliament commemorated Stepan Bandera’s birth as a national hero. Valery Zaluzhny, head of Ukraine’s armed forces and member of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, quoted Bandera: “The complete and final victory of Ukrainian nationalism will come when the Russian Empire ceases to exist.”

Putin uses these examples to accuse Ukraine – seized he claims by a cabal during the Maidan protests – of cultural linguistic genocide, and of being in the control of nationalists and fascists.

Some say we should not care about what happened many years ago in this battle-scarred region. In a nuclear-armed world, the United States and its leadership cannot afford the luxury of an ignorant naivete. As for history, Putin and many Russians do remember. So do Ukrainians.

.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

When is a “what if” a “what about”? It’s always interesting, I guess, to go through the fossil records and look for skeletons. What if Thomas Jefferson turns out to have held views that were common in his day but offend us today?

What if another nation were to use such historic faults, and point to various disaffected parties within the US, as a pretext for brutal military conquest?

Let’s not get lost in the what-abouts.

I assume that this article was misdated and should’ve been issued today, April 1?

A great refresher course in history for those who have forgotten, didn’t know, or don’t care. Looking in the mirror or looking at history, particularly in foreign policy, isn’t something US Americans or the US American government does much of. We are, and have been, very pompous about being in the moral right as justification for our intrusions around the world.

I fail to understand how any of this history remotely justifies the brutal invasion of Ukraine by Putin….the remorseless killer.

Not only is the article astonishing, but the lack of comment is also equally, or even more so, astonishing.

This early history is fascinating and parallels to North American history provocative. I never before connected “slave” with “Slavic.”

The sentence that troubles me, however, is: “Russian memory remains raw of brutal invasions from Europe, leading to the breakup of the Soviet Union.” The Soviet Union broke up not because of memories of German, French, Swedish, Lithuanian, and Polish invasions, but from inherent, internal economic and political instabilities of Communism as practiced by the USSR and eventual rejection by outlying Soviet Republics of central command from Moscow. Under the USSR constitutions of ’24, ’36, and ’77, the Republics had the right to secede and in ’90 they began, one-by-one, to exercise that right (Lithuania being the first.)

thank you for the article