Each spring, as we approach Opening Day, I’m reminded that baseball is about a weird concoction of reality and fantasy, physics and psychics, curve balls and called strikes, nine-digit player contracts and WP Kinsella’s “Field of Dreams.”

And they constantly overlap. I learned this in the spring of 1986, when my 10-year-old son and I signed Cal Ripken Jr. as our personal shortstop.

Colin grew up with baseball. At age 2, he was slapping whiffle balls around Madrona Park. When we migrated east to The Seattle Times D.C. bureau, we found our way to an occasional weekend game at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. By age 5, he was reading the box scores aloud from the Washington Post while I cooked breakfast.

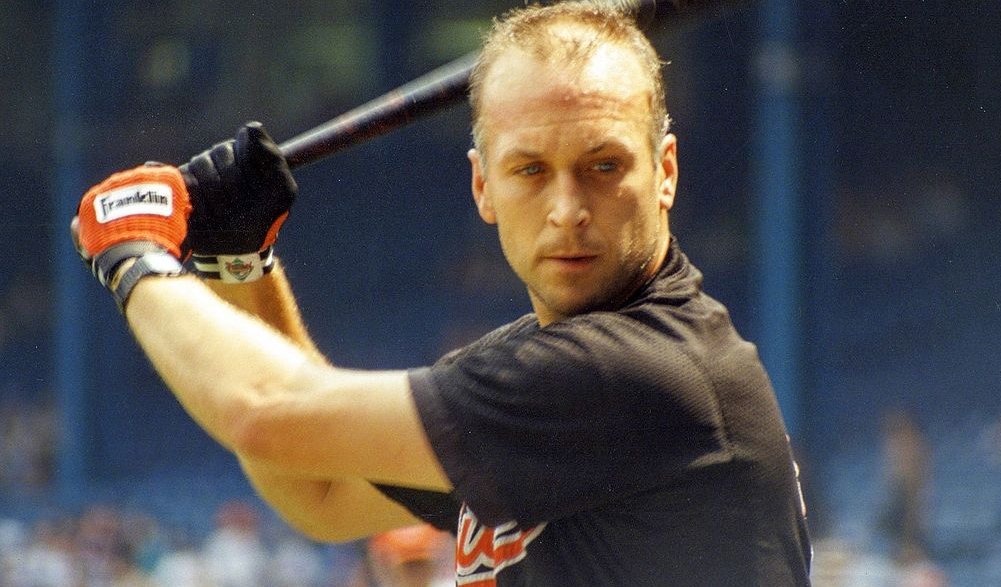

So, at that impressionable age, he became a devoted fan of the Orioles, and particularly of Ripken, the Hall of Fame iron man and the best shortstop in the game. His bedroom was festooned with bubblegum cards, clips from the Sporting News, and a six-foot poster – all Ripken, all the time. He spent hours in his bedroom, swinging imaginary bats at imaginary balls and stealing imaginary bases – just like Cal.

Back home in 1985, we obtained a franchise in the Times Newsroom Fantasy League. For the uninitiated, fantasy baseball (aka “rotisserie league”) had become America’s fastest growing unsport. Here’s how it works: Groups of friends or colleagues organize leagues, with each individual buying a franchise for, in our case, $100. Just before the season, each team drafts a roster of real ballplayers – one at each field position, plus a stable of pitchers and backups. During the season, owners keep track of their players’ daily performance, tallying batting and pitching points. In October, the teams with the most points split the prize money.

We were doing OK with the likes of outfielder Kirby Puckett and first baseman Don Mattingly. But something was missing – Ripken, closely held by my colleague and fantasy baseball guru, Terry McDermott.

We pleaded for a trade: Mattingly for Ripken? Puckett for Ripken?

No deal. McDermott grew up in Iowa, not far from Kinsella’s fantasy field. He knew his stuff. Mattingly or Puckett might score more points, but most first basemen and outfielders are big scorers and most shortstops are not. Ripken would score 100 more points than the next-best shortstop. Gotta play the margins, McDermott said. Gotta play the long haul. That’s the reality.

May, 1986. The Orioles and M’s were scheduled for a Wednesday afternoon game at the Kingdome. An old friend who had worked with the Orioles’ owner called and offered to set up a meeting with Ripken.

I conjured up an excuse for Colin’s teacher, pulled him out of school and arrived at the Kingdome 90 minutes before game time. A public-relations guy in a white shirt and tie lifted Colin over the rail, escorted him into the dugout and introduced him to Ripken. They spent 20 minutes touring the dugout and clubhouse, finally strolling out to the pitcher’s mound. Colin, who barely reached Ripken’s belt buckle, stood agog, his tattered O’s cap tilted sideways as he gazed up into the steel-blue eyes of his hero.

He asked for an autograph. Ripken signed his glove and his brand-new baseball. Then Colin handed him the letter…

Just before leaving the office, I’d typed out a letter that went like this: “Dear Mr. McDermott: For three years, I’ve been your loyal shortstop. Recently, however, it has come to my attention that you are a life-long Yankee fan. This is not a satisfactory situation. Mr. Colin Anderson, on the other hand, is a longtime Orioles’ fan. Obviously, that’s where I belong. Therefore, I demand a trade. Signed Cal Ripken Jr.”

Ripken read the letter, grinned and shrugged. “Sure, I’ll sign that!” he said. And he did.

Back at school, Colin floated several feet off the concrete. He’ll never forget that meeting. Neither will I. It’s etched in my soul like the moment he was born.

I left the letter on my friend’s desk. An hour later, he stomped over, letter in hand, and demanded to know: “Is this real?”

Golly, sure looks genuine.

“Not fair,” McDermott grinned. He had pioneered fantasy baseball, studied its nuances. But nobody had ever dared to taint the fantasy with any reality.

The Trade was consummated – Ripken for Mattingly.

Statistically, it didn’t work out well. Ripken slumped the second half the season, while Mattingly tore it up.

Terry went on to write books, including “Off Speed: Pitching and the Art of Deception,” one of the best baseball books ever.

Colin and I continued to play Fantasy Baseball, always drafting according to McDermott’s strategy. Colin managed the draft, carefully playing the margins.

There may be an important life lesson there. Or maybe not. I’m not sure whether it’s fantasy or reality.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for this story. This is what has made baseball (and sports in general) so memorable for many of us, the personal connections with the players. You and your son will obviously treasure this until the end of your days.

Great story, Ross, even for a non-baseball fan!

Andersons always find a way!