The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has made a “final determination” that the huge open-pit Pebble Mine proposed in Alaska, which would flank two of Bristol Bay’s premier salmon-spawning streams, would irreparably damage rivers and wetlands.

Citing what he called the EPA’s obligation to safeguard “indispensable natural resources,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan has acted under the Clean Water Act to ban disposal of mine tailings in the Kvichek and Nushagak Rivers. Although subject to federal court challenge, the EPA’s action effectively ends the project.

“This is the final nail in the coffin for the Pebble Mine,” said Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash. “The science is clear, the mine would have devastated Bristol Bay salmon and the thousands of hard working families that depend on salmon for their livelihood, subsistence, and recreation.”

Cantwell has fought the Pebble project since 2011, arguing that it would jeopardize fisheries jobs not only in Alaska but the Pacific Northwest. She was the first lawmaker to suggest that EPA use Section 404-c of the Clean Water Act to challenge the mine project on grounds that it would discharge toxic tailings into surrounding streams.

Newly elected Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp-Perez, D-Wash., applauded the EPA’s action, saying: “The Pebble Mine project would have been disastrous for Southwest Washington’s environment and fishing economy, and I’m thankful the EPA stepped up and protected Bristol Bay for years to come.” MGP represents a district along the Columbia River, whose salmon runs have been decimated by hydroelectric and irrigation development.

The Bristol Bay watershed supports the world’s largest wild-salmon fishery, and accounts for about 46 percent of the world’s wild sockeye salmon. Last year was a banner year for the fishery, with a preliminary count of 78 million sockeye salmon, much higher than the 20-year average of 43.5 million fish.

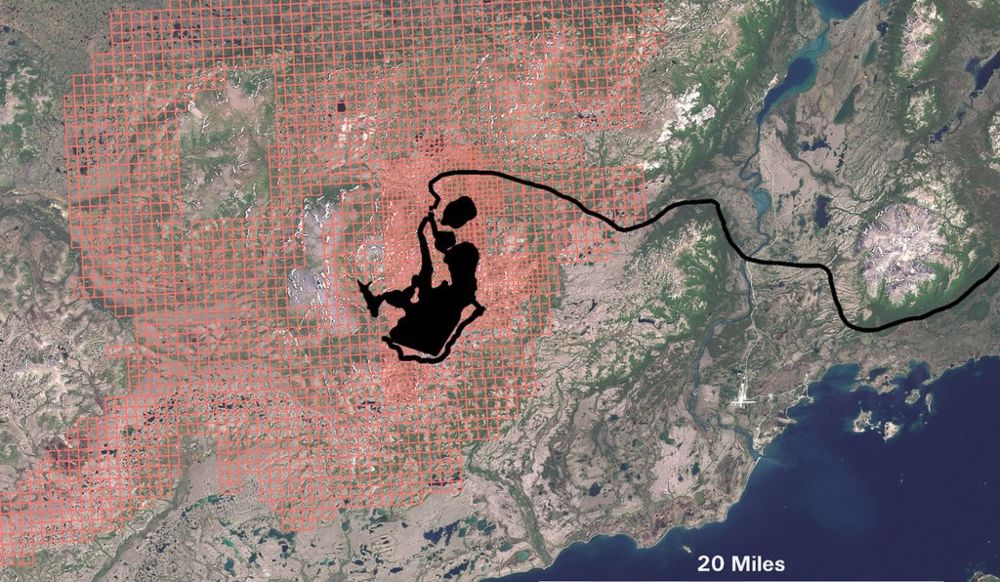

At a Monday phone briefing for reporters, the EPA’s Regan estimated the value of the fishery in the 40,000-square mile Bristol Bay watershed at $2.2 billion, supporting 15,000 jobs in commercial, native, and sports fisheries. Even ex-Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, a mine supporter, has been pictured fishing Bristol Bay in the summer.

“We’re committed to making science-based decisions within our regulatory authority that will provide durable protections for people and the planet, and that’s exactly what we are doing,” said Regan. The EPA reported that the mine, which would cover a square mile and be 1,500 feet deep, would have impacted 8.5 miles of the two major rivers as well as 91 miles of tributary streams, and destroyed 2,100 acres of wetlands.

The Pebble Mine would have produced gold, copper, and molybdenum. Opposition from fisheries, Native groups, and environmental groups had caused major mining companies, notably Rio Tinto and Anglo-American, to pull out of the project. But its sponsors pressed on, boosted by Alaska’s Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy and the late GOP Rep. Don Young.

“This preemptive action against Pebble is not supported legally, technically, or environmentally: As such, the next step will likely be to take legal action to fight this injustice,” the Pebble Partnership said in a statement. It charged that the EPA under Biden “continues to ignore fair and due process in favor of politics.”

In 2020, the Army Corps of Engineers denied a permit to the Pebble project. Its action was surprising, given that the Trump Administration had backed off action under the Clean Water Act. It turned out, however, that Donald Trump, Jr., and Eric Trump are avid sport fishermen, and that Eric’s bachelor party was held in the area. Fox News pundit Tucker Carlson, in one of the few decent acts of his life, also came out against the mine.

The mining industry is a longtime political power in Alaska, used to getting what it wants. Gov. Dunleavy continued to carry the water for Pebble, Tweeting on the latest setback: “EPA’s veto sets a dangerous precedent. It lays the foundation to stop any development project, mining or non-mining, in any area of Alaska with wetlands and fish-bearing streams. My administration will stand up for the rights of Alaskans, Alaska property owners, and Alaska’s future.”

But Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, who has survived two tough elections with backing from Alaska Native groups, was of a different mind. She quoted the late Sen. Ted Stevens, normally a big booster of oil and mineral extraction, saying the Pebble project was “the wrong mine in the wrong place.” But Murkowski was not echoing the celebratory mood of Senate colleague Cantwell.

“To be clear, I oppose Pebble,” said Murkowski in a statement. “To be equally clear, I support responsible mining in Alaska, which is a national imperative. This determination must not serve as precedent to target any other project in our state and must be the only time EPA ever uses its veto authority under the Clean Water Act in Alaska.”

Murkowski is pressing the Biden Administration to approve the Willow project, a major oilfield development proposed by Conoco in Arctic wetlands located just west of the Prudhoe Bay. Oil production at Prudhoe Bay, on which Alaska has long depended for government revenue, is on the decline.

Rep. Mary Peltola, D-Alaska, elected last year to a seat in Congress held by Young for 49 years, cheered the EPA’s action. Peltola is the first Alaska Native to serve in Congress and a fisheries expert. “Protecting Bristol Bay, and the world’s largest sockeye salmon fishery, has been a bipartisan effort from the beginning,” she said. “After decades of uncertainty, I hope that the ruling gives the people who live and work in Bristol Bay the stability and peace of mind they deserve and the confidence that this incredible salmon run will no longer be threatened.”

The environmental movement has learned how to play clever – even rough – during the Pebble Mine battle. In 2020, an environmental advocacy group posed as Hong Kong investors and recorded Pebble Partnership CEO Tom Collier’s boast of having backstage backing from Alaska’s congressional delegation. The project’s boosters also boasted that the big open pit could operate for more than a century beyond its advertised lifespan of two decades. Sen. Murkowski hit the roof and Gov. Dunleavy insisted he was in nobody’s pocket.

The Conservation Fund has also purchased easements on 44,000 acres of land from an Alaska Native corporation near Illiamna Lake, land that sits on the path of the access road Pebble Partnership proposes to build to the mine site. The project is about 200 miles southwest of Anchorage. It is located between Lake Clark and Katmai National Parks on state-owned land.

Sen. Cantwell has also used a variety of gambits to protect public lands and waters. With Republicans in control of the Senate, she managed to put 311,000 acres of Washington’s Methow Valley in the North Cascades off-limits to mining exploration. She used the 2020 Great American Outdoors Act to win permanent authorization and a revenue source for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which uses money from offshore oil leasing to buy up and protect wildlands and recreation areas.

Cantwell has enlisted commercial salmon fishers, cannery operators, outdoor recreation groups, renowned restaurant chefs (e.g. Tom Douglas), and even jewelry firms – from Tiffany to Ben Bridge – in opposition to the Alaska mine.

According to the EPA’s Regan, blocking the Pebble Mine was only the third time in 30 years that the agency has used its authority to block discharges from major proposed projects. The Clean Water Act was enacted in 1972 by a Democratic-controlled Congress and signed into law by a Republican President, Richard Nixon.

Alannah Hurley, director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, praised the EPA’s Clean Water Act findings, saying: “Through all this process, our state government has refused to consider working with us,” and celebrated protection of “the world’s last great wild salmon fishery.” She told reporters: “We’ll be celebrating this decision for decades to come.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.