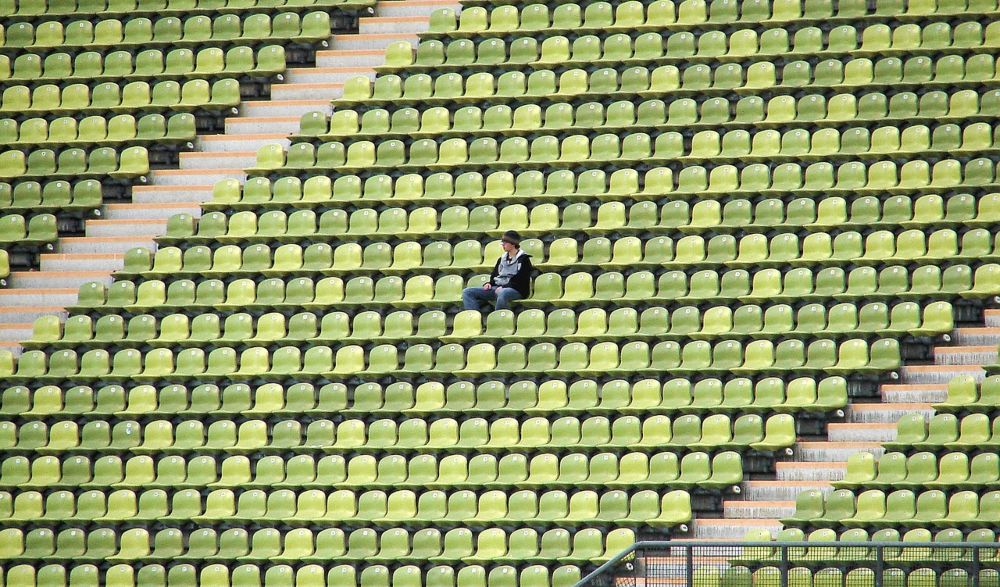

Clergy I talk to tell me that church attendance is averaging about 60% of what it was pre-pandemic. And, for some, that’s the higher end. Will church attendance recover? I don’t know. I’m not sure that’s the right question. But there’s some recent reporting at Mockingbird.com on the relationship between health and social relationships with implications for church.

“Since 1938, the Harvard Study of Adult Development has been investigating what makes people flourish. The simple and profound conclusion: “Good relationships lead to health and happiness.” But these days, people are feeling unmoored and out to sea when it comes to family and friendship. The most devastating and lingering effect of the pandemic, it seems, is “habitual loneliness, in which relationships were severed and never reestablished. Many people — perhaps including you — are still wandering alone, without the company of friends and loved ones to help rebuild their life,” suggests Arthur Brooks in the Atlantic.”

There is, it seems likely, some correlation between “wandering alone,” and “relationships severed and never reestablished” and church decline. There is also a correlation between the social relationships churches typically foster and overall health and happiness. Churches aren’t, of course, the only places for such relationships and one could argue that even there such relationships are a “secondary effect,” not the primary purpose. Here’s more from the Atlantic.

“One such place people experience regular closeness in mind, body, and spirit: church pews . . . (but) it’s easy to become discouraged by shrinking congregations and boarded up church buildings. Writing in the Atlantic this week, Wendy Cage and Elan Babchuk note the integral role churches have in one’s wellbeing and simultaneously assure us that American religion isn’t dead.

Most Americans no longer orient their lives around houses of worship. And that loss is about more than just missing out on prayer services. It means that when people move to a new city, they have to work much harder to find new friends than previous generations did. When someone falls ill, they might not have a cadre of their fellow faithful to offer home-cooked meals and prayers for healing. This reorientation away from houses of worship is one of the factors that has led to the decline of a sense of community, the rise of social isolation, and the corresponding negative effects on public health, especially for older adults.

Cage and Babchuk go on to talk about the things that churches have traditionally done:

“Religion has historically done four main ‘jobs.’ First, it provides a framework for meaning-making, whether helping our ancient ancestors explain why it rained when it rained, or helping us today make sense of why bad things happen to good people. Second, religion offers rituals that enable us to mark time, process loss, and celebrate joys — from births to coming of age to family formation to death. Third, it creates and supports communities, allowing each of us to find a place of belonging. And finally, fueled by each of the first three, religion inspires us to take prophetic action — to partake in building a world that is more just, more kind, and more loving. Through the pursuit of these four jobs, religious folks might also experience a sense of wonder, discover some new truth about themselves or the world, or even have an encounter with the divine.”

That seems to me a fair summary of what churches have done. And a fair summary of what made me think being a church leader was a worthwhile way to spend my life.

But are churches still doing these things? Or do we need to look elsewhere? My answer is “yes.” Yes, some churches are still doing these things and doing them well. But not all. Many churches, made anxious by aging and decline, have become fractious and unhappy. Others, most on the right, some on the left, have let partisan political agendas eclipse their primary reason for being. So some are looking elsewhere.

Cage and Babchuk find that,

“. . . the old metrics of success — attendance and affiliation, or, more colloquially, ‘butts, budgets, and buildings’ — may no longer capture the state of American religion. Although participation in traditional religious settings (churches, synagogues, mosques, schools, etc.) is in decline, signs of life are popping up elsewhere: in conversations with chaplains, in communities started online that end up forming in-person bonds as well, in social-justice groups rooted in shared faith.”

I do think there is life to be found in some long-established congregations. And I think there is reason for seeking and trying new forms of church and other forms of spiritual community.

It seems to me that now — post-pandemic — when loneliness and mental health struggles remain high, churches ought to 1) affirm or re-connect with their core-value and 2) at the same time not simply try to return to or go on with “business as usual.” It is a time for — here’s my mantra — “going deeper and reaching wider.”

I’m pretty sure that the old days of the church as pillar of the community and center of civic virtue are over. But the spiritual need and hunger remain, perhaps greater than in the recent past. There’s never been a better time than now, post-pandemic, for churches to re-think who and what they are, and to re-tool for a new era by going deeper in faith and relationships and by reaching wider beyond our often homogeneous enclaves.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Small, store front churches – outside the “ established” – are proliferating. And what is the reason?