Seattle-born historian Megan Asaka has written an accusatory new account of Seattle’s history, Seattle From the Margins: Exclusion, Erasure, and the Makings of a Pacific Coast City (UW Press, 2022), which contends that our city’s history is imperialist, deeply divided, and an example of “racialized exclusion.”

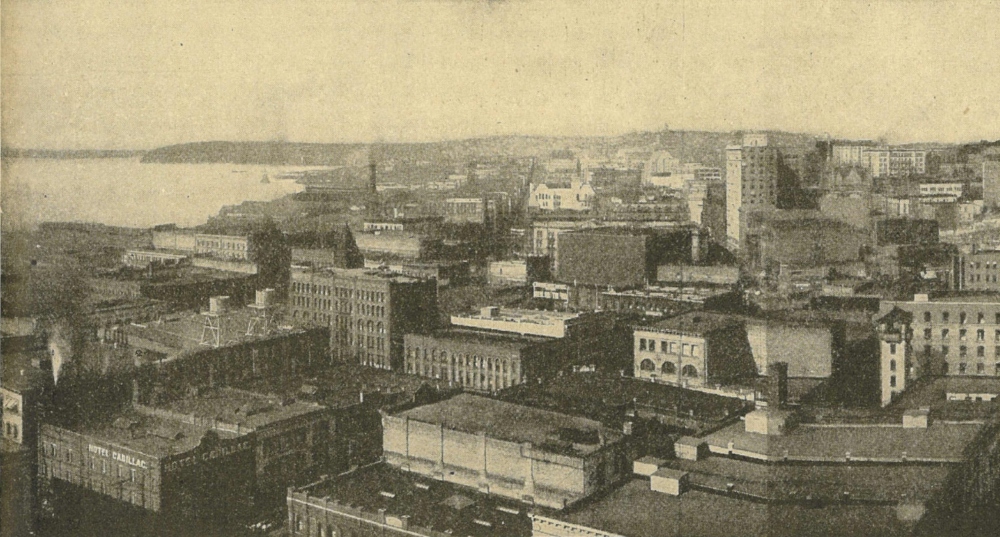

Asaka’s book, bound to be controversial, unearths many new stories and revisionist explanations. Its basic premise is that Seattle was built, 1850-1950, on seasonal, cheap, migrant labor (displaced Indigenous people, then Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Scandinavian), cooped up in shabby hotels in a well-guarded zone south of Yesler Way. That street, in turn, demarks the author’s simplified division of Seattle into northern homeowners and southern drifters.

The book begins with a little-known aspect of local economic history, the growing of hops (used in beer). Those farms, centered on Puyallup, depended on cheap, migrant, seasonal labor — Native Americans and Chinese at first — before a European lice epidemic ended the hops boom. In those days before the railroad, Asaka traces effectively how maritime routes (the Sound and rivers) gave an advantage to seasonal Indigenous workers who would arrive from work at the salmon canneries by canoe, set up camp, and spend the winter in lowly hotels in the Sawdust zone of Seattle (fill from Yesler’s sawmill). From the first, Seattle was a city aimed at a drifting population, and the industry owners preferred to keep it that way and manipulated local politicians for such gain.

The hops paradigm lasted through other extractive and seasonal industries — lumber, coal, laundries, canneries, sex-work, and hotels (a Japanese specialty) — until World War II when Boeing replaced the migrant, cheap-labor economy with unionized industry. In effect, the hops industry serves as a “1619” for Asaka’s basic pattern of capitalist exploitation and racial confinement.

Two important books serve as my paradigms for Seattle history. The first is Nature’s Metropolis (1991), by William Cronon, which describes Seattle and the West as a colonial creation of Chicago and its railroads. The Windy City colonized the West, created the West, in Cronon’s influential account, by encouraging crops and timber and settlements so that the railroads could thrive on business from the imported population and railroad-created markets. Chicago won, but the railroads lost, as Richard White wrote in Railroaded (2011).

The other bookend to the spectrum of Seattle history is Roger Sale’s Seattle Past to Present (1976), which counters Cronon by recounting how locals built an independent city which escaped the colonial trap by going its own often-quirky way. Sale’s book celebrates the creation of “a bourgeois city, capable of sustaining middle-class virtues and middle-class pleasures, large enough to accommodate many variations from its bourgeois norms.”

That bourgeois city is what Megan Asaka dismisses as “a gender bias toward nuclear families and normative domestic life.” Against this “white settler order” Asaka contrasts the fluid, multiracial, hustling, low-key, welcoming culture of the South End and the Sawdust.

Asaka does not take on the late Roger Sale directly (fantasize about the debate they could have!), but one fascinating section of her book deconstructs one of the heroes of Sale’s book, Jesse Epstein, the widely admired man who built Yesler Terrace. Sale admired Epstein for doing low-income housing in a distinctive way and then racially integrating the handsome low-rise settlement that Epstein created.

Not so fast, argues Asaka. Prior to becoming a housing development, that area was a thriving, integrated, affordable, largely Japanese neighborhood that Epstein stigmatized as a slum, “Profanity Hill,” and then moved out the settled low-income population to score federal money for housing. As for the black-white blend that Sale admired, Asaka finds very little was done aside from a “handful” of Black families who survived a secret quota system for entry. She sees it as heartless gentrification, one more black mark for the way Seattle discarded the very people who had built the city and its industry when the modern economy no longer needed them.

One of the strengths of Asaka’s book is the way it writes “history from below,” digging up information about ordinary, struggling, marginalized people who don’t leave records or interest standard historians.

The result is a book that is full of insights, characters, and new story lines. Two examples: how the Chinese fought and killed Natives over jobs; and how the recall of vice-allowing Mayor Hiram Gill in 1910 led to a crusade by the Fire Department and building inspectors bent on closing down the rising (and spreading) number of Japanese-owned hotels.

Asaka’s book can be ideologically simplistic, broad-brushing off as fatally middle class and capitalist much of Seattle’s story as well as complex figures such as Doc Maynard, Chief Seattle’s friend. The book’s values are as an antidote to the triumphalist school of local history, and the trove of new information she discovered by mining fire department records and cheap hotel registers. She goes where few of our historians have thought to look. This brave book is well-written and bracing.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The nickname “Profanity Hill” did not refer to pre-Yesler Terrace. The old King County Courthouse was built in 1890 at 7th and Jefferson. Profanity Hill arose with the expletives uttered by downtowners who had to climb First Hill to get to court.

Osaka’s book (page 222, note 15) acknowledges the courthouse complaints but adds that the name “also carried an obvious double meaning as the neighborhood grew into a center of prostitution and moral ‘profanity.'”

Yeah, but how “obvious” was this? And did it ever carry this secondary meaning? I’m skeptical. Nihonmachi (Japan Town) was a thriving neighborhood with restaurants, retail, live theater, a newspaper and residences. It was chopped up by Yesler Terrace, forced wartime evacuation, and later by Interstate 5. Likely also it had some shady stuff, like every Seattle neighborhood. This was a wide open town.

Bottom-up history isn’t new, but it’s great to see her innovative use of historical resources this way on a local level. Fernand Braudel for South Seattle. I imagine that the progressive hue of academia these days might encourage more authors to undertake projects like this.

As a Swed I have been looking for a license to join the victim and Grievance class. Now I have it in yet another book that adds fuel to fire of unnecessary divisions.

You could claim victim hood if you came from Ballard, which was known citywide as Snoose Junction.

Seriously? Unnecessary divisions? Go read Murry Morgan’s ‘Skid Row’. It was published in like 1950. I wonder if what Morgan described in his tome differs greatly to what Asaka describes in her’s. Doubters all, go pick up a copy and read Morgans’ description of Seattle at its inception.

Lastly, I would hope that those 60+ aged readers and younger will recall that ‘red-lining’ in Seattle didn’t end until around 1968 or there abouts. Red-lining was a practice that occurred for previous decades. No one in there right mind is going to argue or defend the divisions, both economical and damage to the social fabric this caused to citizens of Seattle in future years.

It was really awful.

Morgan’s book was titled “Skid Road”.

Thanks for correction, Gordon. Not only was it titled ‘Skid Road’, but it is still titled ‘Skid Road’, in spite of late at night attempt to re-title it. I recommend reading it (or reading it once again) as well as Asaka’s book.

Megan Asaka (Mr. Brewster – that is the correct spelling of her last name), Lakeside School, class of 1999, has shared interesting research for her book, perhaps from a doctoral thesis on the hop industry in W. WA and racial interactions in that early workforce. Of particular note is Dr. Asaka’s exploration of successes workers had bargaining for better wages, helped by the perishable nature of that crop and shortage of available workers in summer months. However, her concluding observations p.188 that Asians were “swept away” and “The modern city envisioned and enacted by the SHA (Seattle Housing Authority) did not include them” are beyond a stretch, given “what happened next.” “Asian” now is generally described by U.S. census data collectors as the racial group with the highest income level in our country. It would have far more thoughtful for her to have addressed reasons for post-WW II successes of America’s Asian-immigrant and descended workers, vis à vis descendants of the other non-white workers in our region’s early-day hop fields.

Well done David. This new book really does add to what has already been written on this subject.