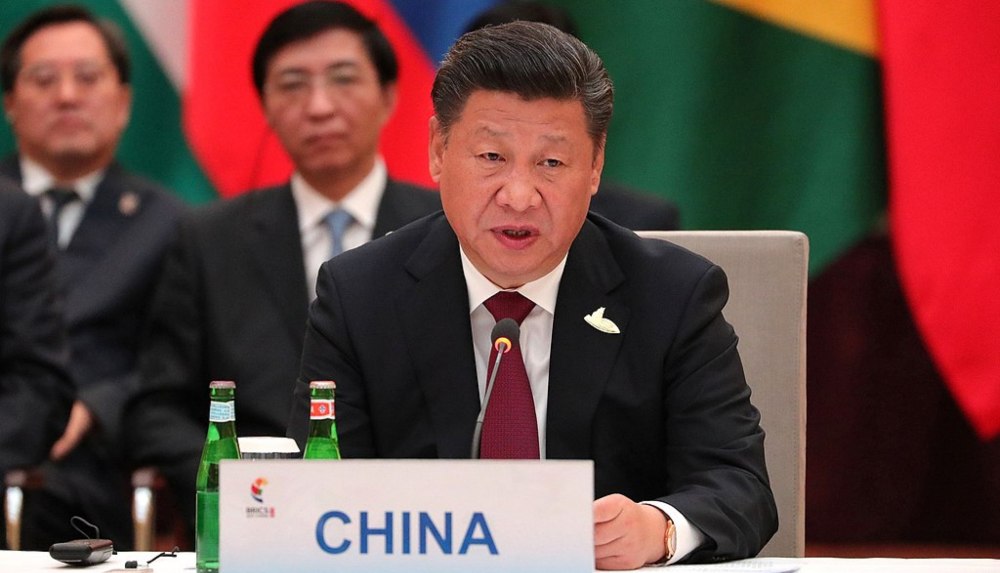

We know as little about Xi Jinping and the direction China may take after last week’s Chinese Communist Party’s 20th National Congress than we did before the Congress. There were no surprises. Most observers agree: No surprises was the whole point of the exercise.

In China, these National Party Congresses are held every five years. In the past they have been a transition to a new Party Chairman/President and a raft of other shifting power titles every ten years. But the 19th Party Congress in addition to hailing the chief, gave Xi Jinping what he wanted, an open-ended term at the top, so no surprises there. He was given the key to as much power as he can muster for as long as he chooses to stay in office.

As for the seven members of the Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, four lost their seats and four new members came aboard. The new members are all Xi loyalists. There was a good deal of speculation by outsiders that Xi might enlarge the Standing Committee and that he might appoint a younger member or two as a possible successor.

He didn’t. Why would he? Why would a man who spent the last 10 years amassing more power unto himself than any Chinese leader since Mao weaken his standing? Why would he signal a possible successor and thereby turn himself into at best a partial lame duck?

Xi appointed men close to him in age as well (Xi is 69). The age of 65, often stretched to 68, is the traditional retirement age for top government officials and ministers in China. (Ordinary citizens face mandatory retirement; men at 60 and women at 50.) The new Standing Committee has one 60-year-old and the rest are all 65 or older. All of the new and old members are either proteges of the Chairman or have demonstrated their loyalty to him time and again.

So it’s now fully a Xi show. What is Chairman Xi’s vision?

Let’s try to decipher the man. In 2014, two years after first taking on the Chairman’s job, two volumes of Xi Jinping’s writings and speeches were published as THE GOVERNANCE OF CHINA. In 2013 I returned to the U.S. from 10 years of teaching journalism at Shantou University in the city of Shantou, a third-tier city of 5.5 million inhabitants at the Northern end of Guangdong Province (the one closest to Hong Kong).

I left China because Chairman Xi no longer wanted any Western influence at any level of Chinese education, except for the sciences where he needed faculty. That “no more Western influence” policy made a contact from The Beijing Review, China’s only weekly news magazine, all the more odd. Like all media in China The Beijing Review is a Party publication. They asked me to review the second edition of the then two volume, more than 1000 pages, of Xi Jinping’s THE GOVERNANCE OF CHINA.

Why me? I’ll never know.

We learn to read fast as journalists, but this was heavy sledding while also being instructive. What struck me was that less than two years into office, the new Party leader had already produced two volumes that, as the publisher noted was “…an authoritative source through which readers can learn about Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era and the guiding principles of the 19th CPC Party Congress.”

That’s also a fair abstract of my review which suggested: If you want to know what Xi thinks and believes, read on. There have been two additional volumes since for a total of four.

The original 18 chapters include Xi’s aims for the economy, The Chinese Dream, with the admonition “Build a new model of Major Country Relationships between China and the United States.” In the chapter on US relations, it’s clear that Xi had no inkling of what President Trump would bring to the party.

Elsewhere there are previews of what has become the Belt and Road Initiative, which Xi then called “Work Together to Build the Silk Road Economic Belt.” It all sounds like what you would expect any politician to do: make promises, often in the hope that few will remember and hold you accountable such promises. The volumes also built a theoretical framework for the Party that emphasized its Marxist roots.

In addition the Party leader outlined a five-year plan in each cycle of the Party Congresses. The five-year plans are blueprints, often with specific goals, most recently to advance a chronically weak national health care system. The government has since acknowledged missing its health care targets when it reviewed the five-year plan, a rare admission from an authoritarian government.

The two volumes have grown to four, nearly 2,000 pages of Xi Jinping Thought. The main surprise in the volumes on Chinese Governance is the extent to which Xi has been open about where he wants to take China.

The goal of building up national defense that has spooked many “experts “ and “analysts,” yet at the same time there is a pledge to peaceful development. While many foreign and expat Chinese observers and commentators all but predicted war over Taiwan, the potential combatants have returned to their corners.

In his 2012 and ’13 pronouncements on “One Country, Two Systems,” Xi limited his remarks to blandly saying, ”Hong Kong, Macao and the Chinese Mainland are closely linked by destiny.” Xi’s view of Taiwan is vague: “Take on the Task of Expanding Cross-Strait Relations and Achieving National Rejuvenation.” Xi’s policy thus far has been his conviction that Taiwan will eventually rejoin the Mainland in some form, while warning foreigners to keep hands off what Xi considers a domestic issue.

The first two volumes emphasize combating corruption. China has been a corrupt state by any measure for centuries, in the form of bribery, threats, and nepotism — all of which was pervasive in my experience. Bureaucratic corruption was institutionalized in China. Xi Jinping understood the history and the system better than most. He saw it first-hand as he rose through his Party career and from the travails of his family during the later Mao years and the Cultural Revolution. There is no evidence that Xi made eradicating corruption a priority as he moved up the Party ranks, but all that changed when he got to the top. He survived a challenge for the top job by a rival with a charismatic personality – not one of Xi’s attributes. Bo Xilai, the party leader in Chungking, a huge city that was corrupt at a level up to and possibly including murder. Bo is now serving a life sentence.

In the two administrations I experienced in China, Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, had the good fortune to preside over the go-go years of China’s explosive economic and social growth. Corruption had a lot to do with getting things done fast in an economy that was growing at more than 10 percent a year for a decade. Chairman Hu’s way of dealing with corruption was to turn a blind eye. According to foreign and Chinese investigative reporting, the Hu family became multi-millionaires and entrepreneurs in the process. Top-to-bottom corruption was endemic. Chairman Hu, like his predecessors, dealt with corruption as a means of weeding out political rivals.

Hu Jintao attended the closing of the Party Congress, where he was sitting, by tradition, next to the current Chairman Xi. At one point he is all but lifted out of his chair and escorted out of the hall. Some see this as humiliation by Xi of his predecessor. The official version is that Hu Jintao felt ill. A close look at the video suggests Hu, now 79, appeared confused and disoriented. (Personal and medical information about party leaders is considered a state secret.)

In today’s China the death penalty seems limited to drug traffickers and violent criminals. In the Hu Jintao era white-collar criminals were routinely executed. Today they are more likely to serve long prison sentences, and even those are often reduced.

The banner of weeding out corruption appealed to the ruling class more than Chinese citizens who knew better, because they had to participate in the corruption to get many things done.

Xi changed that dynamic. He did use weeding out corruption as a political weapon to eliminate real and potential rivals. But he also became a true believer and continues his war on bureaucratic and Party corruption. Some would say it is a hopeless task given the long history of official corruption. But Xi’s increasing control of the Chinese Communist Party has given him the power to mandate changes to behavior.

Xi was open about admitting the Party’s challenge in 2013, one year after he took office: “…we must be fully aware that some (Party) areas are still prone to misconduct and corruption, major cases of violation of Party discipline and state laws have had adverse effects on society, the fight against corruption remains a serious challenge, and the people are dissatisfied with our work in many areas.”

Last week, the 20th Party Congress came and went. It made no waves going in and left no wake coming out. Party political discipline remained firm. There were no leaks about what was to come. There was the predictable unanimous vote from the 2,000-plus delegates confirming everything the Party wanted and ratifying Xi’s new powers.

It had been reasonable to assume that Chairman Xi’s power would only increase at the Congress. His cabinet, the Standing Committee of the Party is now full of the loyal and the faithful. There are no real or potential rivals in the mix. There are also no women in the leadership — a factor that remains a major weakness in the governance system of China.

The big question remains: What will Xi Jinping do with all the power he has amassed?

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m grateful for this well written and concise story (best headline in a long time, by the way). It confirms all of my misgivings about Xi Jinping. After this Congress ended, to one’s surprise, the blankets have settled predictably and comfortably over the heads of the cabinet who can be trusted not to offer him any real challenge. But the women, students, artists, scientists, frontline workers and philosophers are the ones I’m watching in China. The dissenters are remarkably brave, whether a young student confronting tanks at Tiananmen or a doctor raising the alarm about Covid-19 … It will take more than Xi Jinping to muffle them.