On an early spring day when fog twisted like smoke from a locomotive and a stiff wind shooed it gently across the sweet green hills of the Willamette Valley, I arrived at Ken Kesey’s waterlogged dairy farm in Pleasant Hill, Oregon.

It was early April of 1990, several months after the Seattle Post-Intelligencer hired me as a feature writer. This would be my first assignment of any real prove-that-you-can-report-and-write consequence, to profile the man who long ago gave the

world two big brawling books: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Sometimes a Great Notion.

I’d driven down the previous afternoon from Seattle and, always a cheap date when it came to expenses, spent the night with Chinese takeout and a Giants game on TV at a cheap motel on the outskirts of Eugene, ten miles away.

And so here I was on this drizzly morning, breathing in the smell of newly laid mulch. Vast grey skies ran gray and the hillsides above Kesey’s farm had turned a muddy green. I began to stroll the grounds of Kesey’s 70-acre Day-Glo carnival.

Blinking back the light mist, Kesey, plainly tickled with himself, confided to me, “A lot of people ask me why I don’t hire somebody to work the farm, and I say, ‘Well, that’s like having Marilyn Monroe as a mistress and then hiring someone to screw her.’”

Forty-eight cows and two dogs resided then on this madcap compound, along with a wife, Norma Faye Haxby, who Kesey met in the seventh grade and married when he was 21, and a sprawling red farm house, whose innards gleamed of goofy green

floors and orangutan orange wooden steps that spiraled up to Kesey’s writing room.

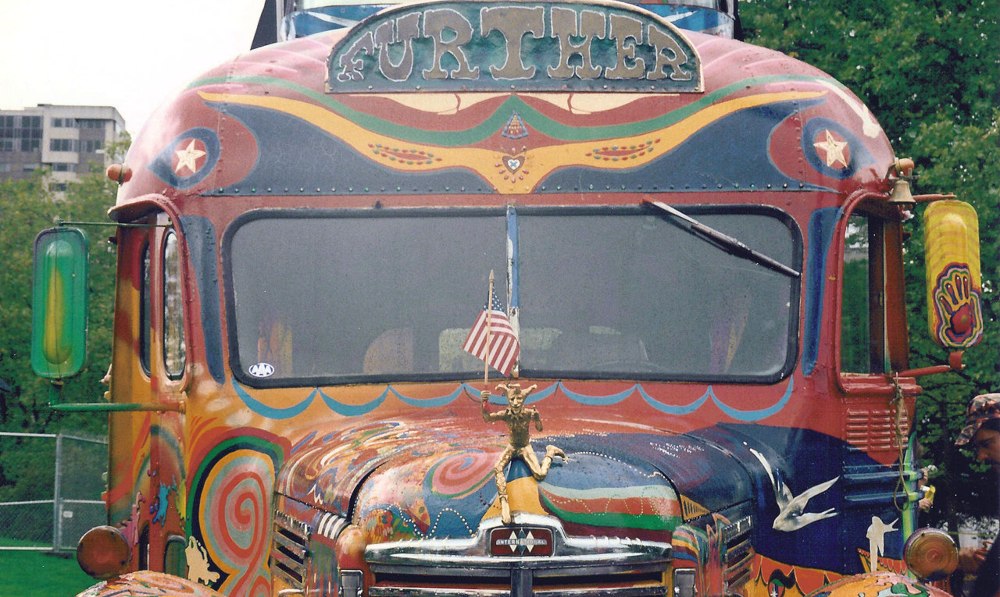

Outside, there languished one very legendary 1939 school bus, The Intrepid Traveler, as it was named, a rusting psychedelic heap that sat squatting in a nearby pasture beside the tall hay barn.

I chuckled to myself when I saw the paper Halloween skeleton with a lunatic smile sitting at the wheel, the one Kesey’s idol, Neal Cassady, piloted a quarter of a century ago, with a troupe of restless travelers who called themselves the Merry Pranksters.

Kesey was adamant when he told me he had no plans to move the bus, not even to the Smithsonian, who sought to house it as a cultural artifact of the Roaring ‘60s.

Nope, Kesey stressed, it’s going to stay out there biodegrading in his barn yard, its paint peeling, forgotten, yet not completely, like a dusty first-place trophy on the mantel. As “Great Notion’s” Hank Stamper had scrawled in his own awkward school-kid lettering for all the Stamper clan to see and live by, NEVER GIVE AN INCH!

Tom Wolfe, of course, resurrected these bump-happy days, recounting the famous LSD bus trip in 1964 across Lyndon Johnson’s America in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the book that forged Ken Elton Kesey as a ‘60s icon.

“It was a great time back then,” Kesey said of the feverish mid-sixties.

I vividly remember now that brief flicker of sadness that slow-danced into in his blue eyes as he said it, as if recounting a gathering of old drinking buddies who had lost the luster they once had.

“Nothing else has really happened since then. Nothing as important.”

Odd, yet understandable, that Kesey would say such thing, as if he were almost proud to be trapped in the shadow of his past. Or, perhaps he resented that the once loud clatter of his life seemed in silent retreat on this soggy April day.

In any case, fretting about his kitchen scavenging for saltines to soak up the smoked salmon, he looked much older than his 54 years. The reddish-hair was nearly gone. There was a ruffle of blond-gray curls plastered at the sides of his head, and his ample stomach strained against the lime-green sweatshirt that read: “I Believe in Poker.”

Kesey was impossibly young when he stole fire from the literary heavens. He was just 31 at the birth of “Cuckoo’s Nest,” and barely 34 when “A Great Notion” came shrieking to life.

“I think writing gets harder and harder,” he told me, sounding apologetic for not having written anything of measure since publishing “Great Notion” in 1964. There was “Demon Box” in 1986, “Kesey’s Garage Sale,” in 1974, and “Caverns,” in 1990. All of them singles and doubles, but no home runs.

“I call it the Hemingway Hump,” Kesey said with more than a trace of bitterness. “Not many Americans make it over the Hemingway Hump.

“You do a certain good thing when you’re young and you don’t make it over that. You go down from that and you glide the rest of the way to the grave.”

He went on.

This, from my notes that recently – and to my shocking surprise – I un-squirreled at my home on the northern Oregon coast: “Faulkner, Steinbeck, Hemingway, Robert Penn Warren, they did it when they were young. Mailer didn’t get any better.

Joseph Heller didn’t get any better after “Catch-22.” I think America drains its writers real fast and leaves them confused.”

Kesey gave me a hard stare, then for a moment glanced out the window to his pond where Purina-fed trout were raising a ruckus in the chocolate-colored water.

On a small hill above the pond, there was a little rise in the ground, I recall, and a wrought-iron fence surrounded it. There, his son Jed is buried. He was just 20 when he and another young wrestler died in 1984 when their van crashed en route

to a wrestling tournament at Washington State University.

“It’s stamina,” Kesey cried out suddenly, throwing back his head and laughing to himself. “When I wrote ‘Great Notion,’ I could go 30 hours at a whack and just grind it out, and I could keep those ideas in the air like balls.

“I can’t do it anymore. I can’t work anywhere near that hard. I can’t keep that many ideas going,” he said, quietly now, petting his pet ferret.

Later, with a harsh whisper, Kesey leaned over and grabbed me by the arm, and he told me, “Ellis, listen to me, there is a time when you set your mind and body to do it, and it does, but you can’t expect it to last. There is a time of grace when you are

in your first flush of creation. One ought to make the most of that.”

I nearly began to cry when he said that to me, and I’m close to tears now, just thinking back to that day, to the feelings I had then during that long interview, most it taking place in his writing room.

The room was large, an enormous shrine to Kesey. I can still recall the walls and shelves and how they brimmed with a lifetime’s worth of memorabilia – the wrestling poster of the “Fighting Ducks,” the Grateful Dead backstage passes, the

licensed plate for THE BUS, and autographed books from writer friends like Larry McMurtry and Hunter S. Thompson.

There too, I remember well, was a photo of him, triumphant and happy, with Faye standing atop Mount Pisgah, the green summit near his home that he’d often go to at Easter.

Kesey, you see, was a hero of mine, and one always hates to feel sorry for one’s heroes.

I admired his brashness, his robust, rambunctious self, the kid voted most likely to succeed by his Springfield High School graduating class of 1952, the writing whiz at Stanford, where, with LSD as his lantern, he would write “Cuckoo’s Nest.”

He even took a few electric shock treatments to know the horrors of a mental hospital. I asked him why, and he offered this simple reply, “It was dumb, but back then, you had brain cells to waste.”

It took Kesey three years to convince the writing authorities at the University of Oregon to let him teach a creative writing class. “They thought I’d turn them into little Keseys,” he said with a rumbling laugh.

By now, it was time to feed the cows. I can still see Kesey yanking on his dark blue overalls with hands he once moved like lightning as a college wrestling star, his neck still as big as an oak stump.

Rolling along with his son Zane on their old blue Ford tractor, the gentleman-farmer cut open and scattered bales of hay, all the while posing like a movie star for pictures.

I asked him what it was like teaching the writing class at the U of O.

“They all worry too much about their stuff,” he replied. “I told them not to worry. Just write it. Fiddle with it later. Just enjoy the rush you get when you’re able to write, before it becomes something you have to labor over.”

Ken Kesey died at a Eugene hospital on November 10, 2001. He was 66.

He lived a life full of incident and rarely gave an inch.

So may we all.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A terrific story — glad you shared it with us, Ellis.

What’s as good as reading a 628-page book by Ken Kesey? Reading your short story about him, Ellis. Good job.

I always though the bus was named “Further,” but maybe that was the destination. Kelsey’s been a hero of mine since the 70s. In later years, it was always fun to see his antics at the Oregon Country Fair. Good story.

Thank you for bringing the Ken back to life for a brief moment. We all slow down especially if we burn hot at the beginning.

I wonder how soon after your visit he started Sailor Song, published in ’93? It wasn’t on par with his first two epics, but he did prove he could write another one and it wasn’t bad.