The least expected Northwest visit by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip came in the early 1960s, when powerful headwinds forced a return to Vancouver by a Fiji-bound royal flight. Usually, arrival of Royals required days of meticulous attention to detail. On this occasion, preparation was compressed into hours.

The royal suite at Hotel Vancouver was hastily prepared. A Rolls Royce had to be secured and was loaned by the owner of nearby Georgian Towers Hotel. Vancouver Police were pressed to provide security. A senior constable rode shotgun in the Rolls’ front seat and a police radio was installed on the dashboard.

Then, riding in from the airport, the unexpected. Vancouver’s Finest were raiding a house of ill repute in the East End. Bawdy talk filled the radio. The embarrassed constable reached out to silence the speaker. But a hand glided out from the back seat and stopped him. “Leave it on!” commanded Prince Phillip.

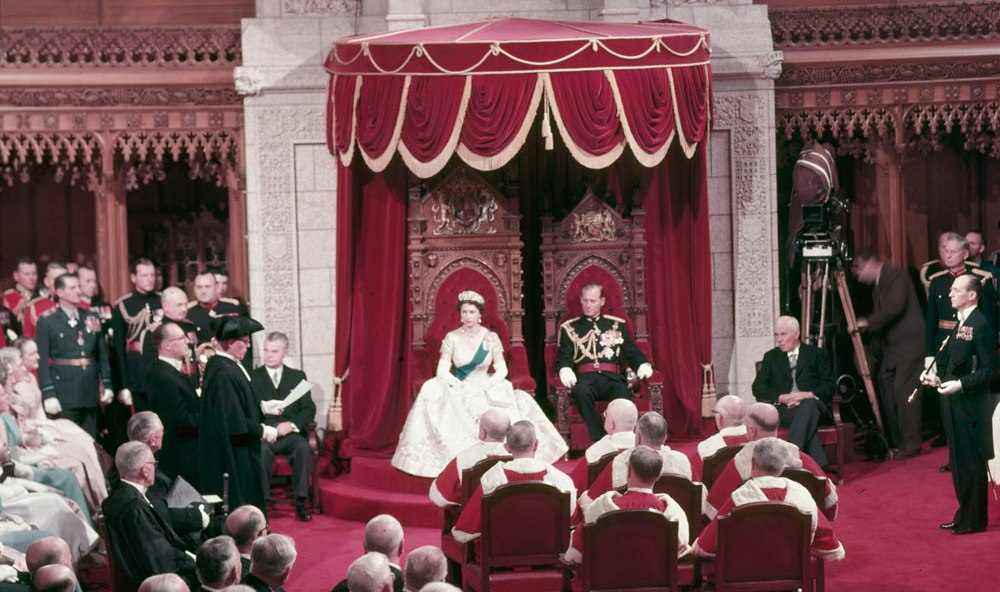

The Royals have been frequent visitors to our region. “The Queen held a special place in her heart for British Columbia: We were honored to host the Queen seven times, six as reigning monarch,” B.C. Premier John Horgan said Thursday. Her Majesty sailed into Elliott Bay on the (later jettisoned) royal yacht Britannia in a 1983 spring rainstorm.

Such is the seven-decade tenure of Queen Elizabeth II that coverage of her visits was passed down for generations. My mother copped a Life magazine byline with an account of the Royals’ unexpected Vancouver visit. Four decades later, I reported on QEII dropping a puck at center ice before a Vancouver Canucks hockey game.

British Columbia visits became a venue for watching how the Royals worked. At a post-puck-dropping news conference, I asked a snarky question about why Western Canada needed a ceremonial head of state from across the Atlantic. Hockey great Wayne Gretzky delivered an articulate reply on the value of the Queen’s serenity and continuity, and as a uniting force in the Great White North.

A day later, I was amazed to see The Great One’s comments become headline material in British tabloids. The papers were relentless in probing the Royals’ private lives and tormenting their romantic interests. Yet they could turn around and banner Gretzky’s defense of the monarchy against questioning from the former Colonies.

Prince Phillip was a decorated naval officer and Exhibit A of the alpha male. I had long wondered how he could stand having to walk behind his spouse and endure the title “consort.” British Columbia offered lessons in how a 73-year marriage worked. Phillip did his thing — productively. He took off to meet with young recipients of the Duke of Edinburgh Award, a youth development program launched by His Royal Highness in 1958 and since extended to more than 100 countries. He tapped Sir John Hunt, leader of the British expedition that first climbed Mt. Everest, as its organizer.

Prince Phillip flew north of Prince Rupert, by float plane, to dedicate the Khutzeymateen Provincial Park, in a river estuary filled with feeding grizzly bears. The sanctuary was established over timber industry resistance. HRH lingered with detailed questions on how the park was being jointly managed by the province and Aboriginal First Nations. A cogent inquiry, in that Phillip was longtime chairman of the World Wildlife Fund.

The disciplined Queen, meanwhile, went through a civic luncheon. An essential duty, decade after decade, was greeting hundreds of people, making small talk about where they were from and what they did. The understated royal wit was heard, as in the 1983 visit when the HRH’s had to endure foul weather all up the West Coast, after sitting through an unending Hollywood variety show staged by Frank Sinatra.

The Queen bestowed on British Columbia its official Coat of Arms, described by Horgan as “an important symbol of our independence and sovereignty.” On another visit, she showed up to open the Commonwealth Games. With a royal moniker, the provincial museum in Victoria was able to use the title of Royal British Columbia Museum.

British Columbia has been a place to read the Royals’ popularity. Prince Charles and Camilla were mostly ignored during a B.C. visit that took when they were a couple but not yet legally coupled. By contrast, Princes William and Harry as teenagers enjoyed a rock star reception when their father took them skiing at Whistler.

The most famous recent Royal sighting came at Christmastime in 2019. It was the beginnings of “Mexit,” the withdrawal across The Pond from royal duties by Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, aka the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. The Sussexes decamped to Vancouver Island just before the Queen’s formal, stifling Sandringham Yuletide feast and pheasant hunt.

At a borrowed $13 million mansion near Sooke, they plotted a half-and-half arrangement, continuing some royal duties while putting their own brand “Sussex Royal” on independent activities. Back in London, Her Majesty put it on the line: You’re all in, or you’re out. No use of Sussex Royal, no moneymaking engagements using the Royal Highness titles.

Our region witnessed the second Elizabethan age at its height of popularity – the gridlock of yachts greeting Britannia in Elliott Bay. The celebration of British Columbia’s 100th anniversary took place ironically just as popular Royals plotted a royal split. These Windsors have been interesting to have around.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks for the look back with your great article on the royal visit to BC.

Queen Elizabeth II also visited Seattle and spoke at UW in 1983. Here’s a link to one story about the visit. Note that beloved history professor Jon Bridgman–my favorite professor and a good friend–led the procession for the queen.

https://magazine.washington.edu/when-the-queen-came-to-the-uw/

Gratefully, Robin