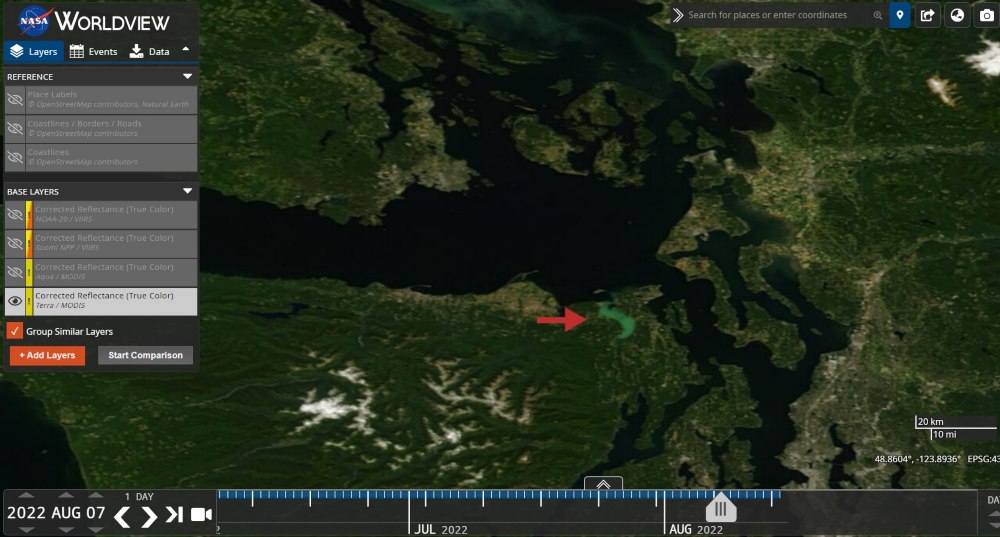

A week or so ago, folks in the Port Townsend area found themselves gawking at Discovery Bay, wondering what to make of the strange turquoise color that stretched shore-to-shore. They weren’t the only ones. NASA scientists were seeing the same thing in satellite photos – a brilliant aqua-hued bay surrounded by the normal deep blues and greens of Puget Sound Country.

Word spread fast online with dire warnings of a massive toxic bloom, punctuated by tearful emojis. Fishermen wondered if it was safe to eat Dungeness crab pulled from the cloudy bay. Others worried about the health of a humpback whale that had been cruising the bay for a few days.

It turns out, Discovery Bay’s turquoise lightshow was due to an extraordinary bloom of coccolithophore – most likely the subspecies Emiliania huxleyi.

Huh?

Cocolithophores are a phytoplankton more familiar in places as near as Hood Canal or as far as north Australia. They are shaped like soccer balls, 5 to 10 micrometers diameter, so they easily slip through plankton nets. Placed side-by-side (don’t try this at home,) there would be hundreds or even thousands to the inch. Scientists need an electron microscope to see them.

Yet there were enough of them in Discovery Bay to be photographed from space. The organisms are not aqua colored, but rather reflect light, which explains the turquoise hue. They’ve been out there for millions of years, an important part of marine ecosystems and even terrestrial geology. These are “the same tiny photosynthetic diatoms that make up the White Cliffs of Dover,” says Betsy Carlson at the Port Townsend Marine Science Center. “They are not toxic and no cause for concern.”

To most of us, Puget Sound conjures up images of silvery salmon, leaping orca whales and spindly Dungeness crab. But those charismatic superstars ultimately depend on countless trillions upon trillions of microscopic plants and animals known collectively as plankton. These invisible critters make up the primordial soup that is the basis for all life – and not just marine life.

School kids occasionally get a glimpse through a microscope at a few of them –shrimplike copepods or Aspirin-shaped diatoms or any of a thousand species in between. Planktonic life is out there year-round, but it is cyclical, peaking in the summer when long days trigger a biological explosion known as a “bloom.” Puget Sound waters, relatively clear during the winter, suddenly turn murky and green – especially in long fjords like Hood Canal.

The murkiness irks fishermen and scuba divers. But it signals life. The marine ecosystem is shifting into higher gear. Nurtured by sunlight, plankton begin reproducing themselves, quickly becoming billions and trillions. In his 1983 book, “The Fertile Fiord,” University of Washington oceanographer Richard Strickland wrote: “Puget Sound is to plankton what Florida is to oranges, what Iowa is to corn, and what the Cascades are to Douglas fir.”

Teri King, a water quality specialist at Washington Sea Grant, responded that way last week when she noted areas of cloudy turquoise on Hood Canal. Her immediate thought was coccolithophore, which is not uncommon in that area. But then it showed up Discovery Bay, where the last such bloom was in 2016. These blooms, she says, are associated with water stratification – warm water at the surface and cold water below, with little or no mixing. They occur in subpolar regions around the world – in recent years as far north as the Bering Sea.

And scientists believe they may actually be beneficial. When coccolithophore reproduce, they use carbon atoms which otherwise contribute to harmful acidity in the ocean. And they have anti-virus and anti-parasite qualities that have intrigued scientists for years. And what about that humpback whale, swimming through a coccolithophore cloud in Discovery Bay? It may have been coincidental, King says. Or maybe not.

Cocolithophore plankton are too small to be eaten by whales, but they make excellent meals for zooplankton, which in turn are consumed by small fish, which are consumed by larger fish such as herring. And humpbacks feast on herring. Even amid the murky bloom on Discovery Bay last weekend, gulls massed at the surface, perhaps feeding on a concentrated ball of herring. And the humpback was in the same neighborhood.

“The only problem is the whale wouldn’t be able to see much,” King says.

But the NASA satellite saw plenty.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Lovely piece