In a letter dated June 10, 1815, Thomas Jefferson wrote to John Adams: “I cannot live without books.” His collection of 50 years consisted of about 10,000 volumes. Thereby hangs a tale about the first traveling library to make it to the West Coast.

In 1801, the new President Jefferson hired 29-year-old Meriwether Lewis as his secretary. Lewis had been an army officer with extensive experience in the West. His working area in the East Room of the President’s House (later called the White House) was shabby, but Jefferson’s library was next to Lewis’s sleeping quarters on the main floor.

In early 1803, Jefferson asked Congress for an appropriation of $2,500 to undertake an exploring expedition, led by Meriwether Lewis. Jefferson told Spanish authorities that the expedition was a “literary expedition,” downplaying the political implications. In fact, Jefferson’s interest in science, along with the political ramifications of an American presence among Spanish, British, and Russian western outposts, were the principal reasons for what would be called the Corps of Discovery. But “literary” is also a dimension, explored in this essay.

Appreciating that Captain Lewis needed more education for the expedition, Jefferson sent him to Philadelphia, hometown of the American Philosophical Society. Jefferson wrote a letter to Dr. Benjamin S. Barton, the noted linguist and collector, in which he mentioned Meriwether Lewis. Jefferson noted of Lewis that it “was impossible to find a character who [has a background in] science in botany, natural history, mineralogy, & astronomy, joined [to] the firmness of constitution and character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods, and familiarity with the Indian manners & character.”

Meriwether Lewis spent weeks in early 1803 with Dr. Barton, Caspar Wistar, M.D., Professor Robert Patterson of the University of the University of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Rush, M.D., and other eminent men in that Enlightenment City. Lewis also visited Andrew Ellicott, distinguished astronomer and surveyor, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Closer to home, Albert Gallatin, Jefferson’s Secretary of the Treasury, and Henry Dearborn, Secretary of War, counseled Lewis.

Did Lewis carry his own library across the North American continent? Neither Lewis nor his co-captain William Clark left many direct references to “books” in their Journals. However, the written record of their adventure suggests they frequently used scientific sources at hand, both on the trip and in writing up the findings afterward. Clark mentioned several such volumes upon his return from the far west. Also, scholar Elijah Criswell lists nearly 200 scientific words used by Lewis, “every one of which he must have recalled from scientific books.”

The following books have been cited by scholars and historians as being within reach of Lewis, or mentioned by him or others in connection with the expedition.

- The Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, a four-volume work printed in 1754-1755. Sometimes referred to as Owen’s Dictionary, the work was published in London.

- Cyplopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, by Ephraim Chambers. Published in 1728, this work resulted in Chambers gaining membership in the Royal Society. The Cyhplopaedia spawned an American edition and other similar works. When Lewis wrote a description of salmon at Fort Clatsop, Oregon, his language closely followed words in Owen’s Dictionary.

- Histoire de la Lousiane, 1774, by Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, was a result of du Pratz’s long residence in Natchez and New Orleans. The record shows that Lewis borrowed a copy of the second English edition (1774) from Benjamin Rush.

- Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, 1778. This was an eight-page pamphlet written by Dr. Rush, and used during the Revolutionary War. It went through numerous printings. Scholars assume that this popular guide/pamphlet was carried by the Corps. This little work was supplemented by copious medical advice, a medicine cabinet, and an assortment of pills, including “Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills,” also known as “thunderbolts,” a strong purgative.

- Johann Sebastian Muller’s An Illustration of the Sexual System, of Linnaeus, 1779, was probably on hand. This and other Muller books served to identify plants that Lewis saw and collected.

- Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops . . . Articles of War, 1794. The American versions of these works were written by German-born Frederich W.A. von Steuben. After service in Europe in the Seven Years War, he joined George Washington’s staff at Valley Forge, later becoming Inspector General. His writings addressed almost everything of concern to a soldier: sanitation, drill, food preparation, and general conduct – including courts martial.

- Lewis purchased Richard Kirwan’s Elements of Mineralogy, 1794. Kirwan was an Irishman, who devoted his life to chemistry. In 1780 he was elected to the Royal Society. An example of Lewis’s probably using Kirwan occurred at Tillamook Head, Oregon, where Lewis employed terms to describe the minerals, earth, and colors of that scenic natural monument that may have been lifted from Kirwan’s work.

- A Practical Introduction to Spherics and Nautical Astronomy, by Patrick Kelly, 1796. Although Kelly was primarily interested in finding longitude and latitude at sea, Lewis converted the information to overland travel. The Corps, however, had problems with their timepiece, which was essential to determining longitude.

- Robert Patterson provided Lewis with an astronomical notebook for lunar calculations. Jefferson insisted that mouths of rivers, rapids, islands, and other natural marks be used to determine the Corps’ location.

- Astronomical tables for the Corps were compiled by Nevil Meskelyne. Lewis used Maskelyne’s Table Requisite 1766-1802, and Nautical Ephemeris 1804-6.

- New Views of the Origin of the Tribes and Nations of America, by Benjamin Smith Barton, 1797, was either given to Lewis by the author in Philadelphia or purchased by Lewis. Barton organized his volume for easy reference: roots, bulbs, trunks, leaves, and flowers. Using Linnaeus’s sexual system, Clark confirmed that he and Lewis were able to classify bulbs, roots, and flowers with the help of Barton’s works.

- Alexander Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Lawrence, through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen and Pacific Ocean; in the years 1789 and 1793. Voyages was a famous book read by both Jefferson and Lewis. It was published in 1801. Parallels between Mackenzie’s and Lewis’s descriptions can be found in describing venereal diseases; another similarity was the listing of vocabularies for Indian languages. Both Mackenzie and the Corps carved their names on trees and rocks along the continent’s west coast.

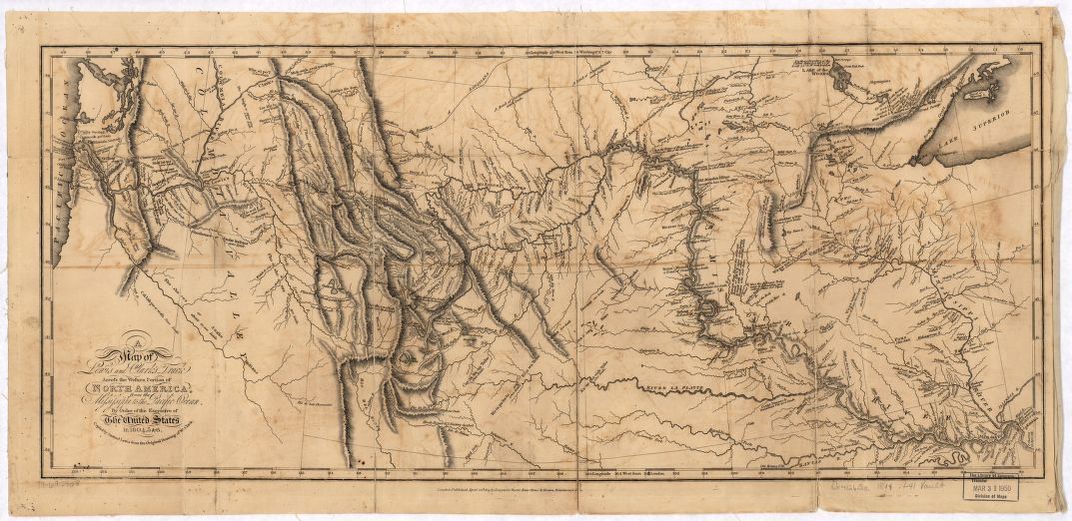

In addition, maps and more maps were rolled up, wrapped in skins, and hauled everywhere. Many cartographers were credited with these early maps, including Le Page du Pratz (Louisiana), James Mackay (Missouri River), John Evans (the mouth of the Missouri and the Mandan villages), Antoine Soulard (Upper Louisiana and Upper Mississippi), and David Thompson (Columbia River). A famous cartographer, Aaron Arrowsmith, author of New Discoveries in the Interior Parts of the North America, provided maps used by Jefferson and Lewis.

Meriwether Lewis’s Traveling Library may have been the first of its kind to cross the North American continent (although Sir Alexander Mackenzie certainly carried maps and perhaps a few reference works during his earlier voyages).

It is likely that Indians along the route were fascinated with these strange papers. Virtually everything carried by the Corps was believed by the Indians to be “Big Medicine.” Certainly, Sacagawea recognized their value, and she rescued part of the written records when one of the pirogues capsized on the westward trip up the Missouri River.

The forces behind Meriwether Lewis’s Traveling Library, other than Jefferson’s wide-ranging curiosity, were the winds of the Enlightenment. The Western world now valued clear thinking, facts instead of mysticism, restless curiosity, and the discovery of new lands. All this had launched a different way of looking at the world.

Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society was a knock-off of London’s Royal Society. Universities were founded. Men’s clubs fostered animated discussions. Two great social and political revolutions occurred, one in America and the other in France. Science was in the forefront, with such leading figures as Spain’s Jose Mariano Mozino, England’s Sir Joseph Banks and Archibald Menzies, Russia’s (and Germany’s) Wilhelm Steller, and in America Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin.

Was the Travelling Library returned to St. Louis and other eastern points? Evidence suggests that many of Meriwether Lewis’s volumes made it home. Several of his books have surfaced at the American Philosophical Society, in several museum collections, at Monticello, and in the Smithsonian Institution.

Thomas Jefferson’s love of books is illustrated by a catalogue of his library which he drew up in 1783. He sold a large part of his library – at a bargain price – to the Library of Congress after that library suffered a fire set by British troops in the War of 1812. Dumas Malone, Jefferson’s eminent biographer, noted that Jefferson “had an abundance of books; sometimes he would have twenty of them on the floor at once.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.