The world of birds is on the move, and that includes the Olympic Peninsula. We now have hummingbirds in winter and scrub-jays moving in from the south. More northerly species, such as white-winged scoter and long-tailed duck, are becoming scarcer in winter, presumably because they are staying farther north.

This is part of a worldwide shift in ecosystems occurring due to climate change. It began in the mid-1980s, affecting everything from ocean temperatures and krill to butterflies. With birds, a plethora of studies are concluding the following:

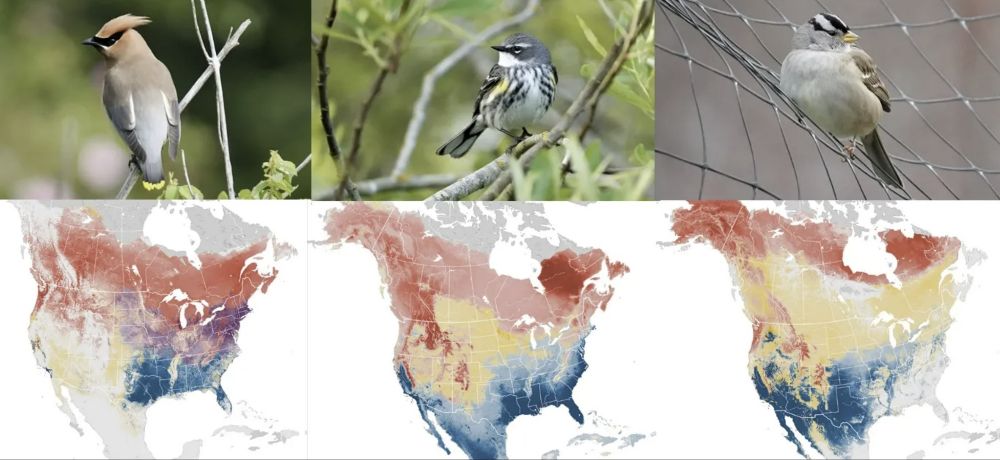

- Many birds are shifting their ranges poleward, especially non-migratory species and short-distance migrants.

- Some birds are shifting their migration timing and laying eggs earlier, but for most, not enough. Many long-distance migrants are the least adaptable.

- Many species, both resident and migratory species, appear to be physically evolving in small ways to adjust to warmer temperatures.

- Finally, there are many special cases, birds with unique niche habitats or habits, which may be unable to adapt.

Range Shifts

Those with hummingbird feeders probably know that we have rufous hummingbirds in summer and Anna’s hummingbirds year-round. That hasn’t always been the case.

As recently as 2004, Anna’s Hummingbird was not found on the Port Townsend Christmas Bird Count (CBC). Last December we counted 146, another new high count. The Sequim CBC tallied 404. In 2004, they had two. Anna’s hummingbirds have become one of the most common birds in Seattle, Vancouver, and Victoria, and are over-wintering in Alaska in increasing numbers each year.

A long list of other birds are expanding from California and Oregon into Washington and beyond: great egret, red-shouldered hawk, black phoebe, California scrub-jay, and lesser goldfinch, to name a few. The scrub-jays are already established in Port Townsend. Sequim’s first lesser goldfinch was found this May. Port Angeles had their first last May. We are also seeing an increase in birds spending the winter here, where previously they primarily went further south.

It’s important note what is not expanding north from California: Nuttall’s woodpecker and oak titmouse. These are oak dependent species, and oaks can’t fly and are slow to spread and mature. With oaks dying across California due to drought and fire, these species are having the rug pulled out from under them with nowhere to go. In Washington, both the Sequim and Port Townsend CBCs show a marked decline in Eared and Western Grebes. These species nest at inland lakes, where drought may impact breeding.

The Timing Problem

A major concern is what is called a phenological mismatch; in short, a timing problem. Compared to the mid-1980s, leaf-out, first blooms, and peak caterpillars, generally associated with native trees, are now one to two weeks earlier across much of the United States and Canada. When migrants arrive on the breeding grounds and begin egg-laying, they are missing peak insect supply. As a result, fledgling success suffers. Considerable research has found that birds, on average, are laying earlier, but not enough.

Evidence suggests that local resident (non-migratory) birds are sometimes able to adjust, but long-distance migrants are not so flexible. It may seem counter-intuitive that long-distance migrants are less adaptable. After all, they fly thousands of miles each year to find the right food. In this, however, they appear to be hard-wired by daylength. Time will tell how this impacts the Olympic Peninsula’s long-distance migrants: olive-sided flycatchers, Pacific-slope flycatchers, willow flycatchers, Swainson’s thrushes, Wilson’s warblers, MacGillivray’s warblers, orange-crowned warblers, yellow warblers, western tanagers, black-headed grosbeaks and others.

(Photo: The Pacific-slope Flycatcher is a long-distance migrant.)

Heat waves can also impact late nesting species. I am remembering last summer when the Pacific Northwest suffered a heat wave described as a thousand-year event. Desperate to get off hot rooftops, young Caspian terns hurtled themselves into Seattle traffic. Swallow chicks cooked in their nest boxes at marinas. Fortunately, I see that this year around Port Townsend most species have already fledged young – and heat has not been an issue yet. During the first week of June, I noted newly fledged American crows, black-capped chickadees, American robins, house finches, white-crowned sparrows, savannah sparrows, song sparrows, spotted towhees, and red-winged blackbirds. In my yard, where I’ve carefully situated nest boxes for afternoon shade, chestnut-backed chickadees and Bewick’s wrens were on eggs. I hope they hurry up.

Evolution

As incredible as it may seem, birds are already noticeably evolving with our warming climate. Dozens of species have grown physically smaller since the 1980s. Most of these have also grown longer wings. This is predicted by Bergmann’s Rule, in which species in hotter climates are smaller, presumably to stay cooler. They make up for reduced flight muscles with longer wings.

Evolution is at work, but is it fast enough to keep up with rapid climate change? In one study in the Mojave Desert, where nearly all species are declining due to climate change, birds with smaller body size and greater cooling ability fared better, though the analysis calculated that increased heat and aridity was outpacing all species’ ability to adapt.

Ecosystem Cascades

All birds, whether or not they change, face changing communities around them. This may mean new predators, lost food base, new competition, new parasites, or a cascade of secondary effects as changes ripple through flora and fauna. In my neighborhood, I wonder if the newly arrived California scrub-jays, fierce nest predators, will affect the nest success of American Robins.

Rapid Climate Change

Birds, as a group, have been through climate warming before. Many of today’s bird families existed during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) 55 million years ago. The earth warmed 5 degrees Celsius (almost 9F), creating tropical ecosystems as far north as Wyoming. There were alligators inside the Arctic Circle.

Birds did well, evolving through it, because the PETM, one of the world’s most rapid climate warming events, actually took 5,000 years. An animal living through it would scarcely have noticed. On average, the earth warmed 1C every thousand years. Since 1981, the earth has warmed at a rate of 1C every 56 years, or 18 times faster. The current warming is so fast that it is noticeable within a few generations of birds, or even within the lifespan of an individual bird. Birds – and everyone – need to adapt immediately.

Have you a theory on how humans will adapt ?