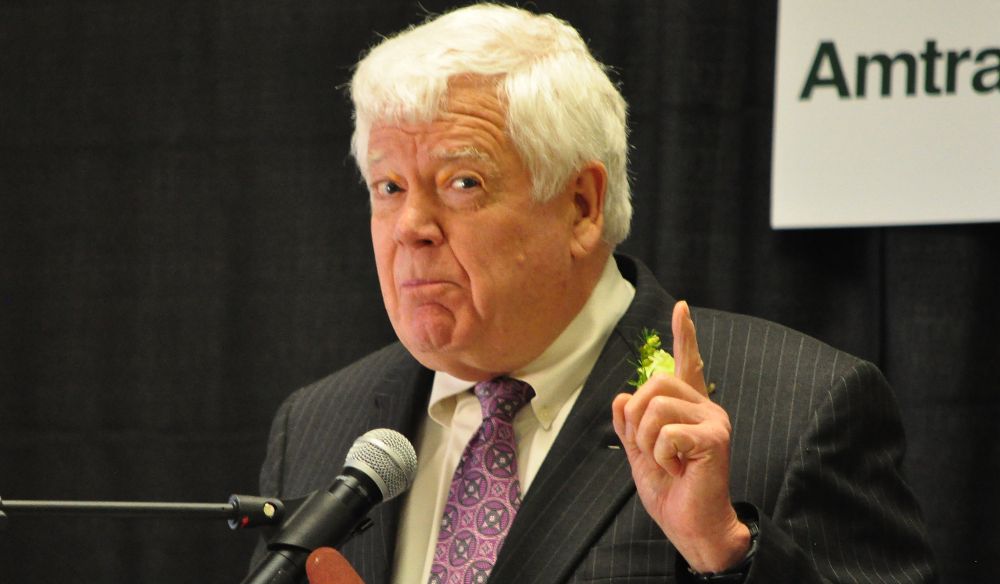

The reader of Money, Love and Power: A Guide to Understanding Congress by Jim McDermott, for whom the U.S. House was home for 28 years, will come away questioning the judgment of anybody who chooses to endure the punishment of dialing for dollars, running and serving.

Demands of fundraising are “grueling and mind deadening” even for someone representing Washington’s overwhelmingly Democratic 7th District. “I had to raise $250,000, every two years, to keep my seat on the House Ways & Means Committee,” McDermott told friends in a Zoom call from France, where he wrote the book.

The money was not to court Seattle voters but went into House Democratic Caucus coffers. When McD came in at $214,000 one term, colleagues questioned whether he should chair the health subcommittee, a post for which the psychiatrist-lawmaker was notably suited.

Constantly shuttling between Washington, D.C., and his district, “You don’t have time for your family,” said McDermott. I count eight House members from Washington and Oregon, including McDermott, who’ve been divorced while serving in Congress.

What, then, moves people to this life? Power is an attraction, along with a genuine desire to get something done for your community. And the limelight. A member of Congress is “always on display,” McDermott writes. “Every mike is ‘hot,’ every telephone is a camera, and every reporter has a record button.”

McDermott has war stories to tell and war wounds to show. As a state senator, he ran for Governor in 1984, and blew away Democratic opponent Booth Gardner in a Rotary Club debate. Gardner, a Weyerhaeuser heir, decided to double down and wrote a check to his campaign for $500,000. He won going away.

Money, Love and Power will have anyone who knows McDermott nodding approval at times and staring skyward at others. As a University of Washington grad student, I canvassed Laurelhurst in 1970 when the young doctor broke Republicans’ grip on the 43rd Legislative District. Years later, I coined the description “congressman-for-life” to describe McDermott’s languid performance as a minority House member.

The book is a sharp, spot-on critique of Capitol Hill’s current clumsy dysfunction. Congress used to be collegial, with friendships across the aisle and a transactional culture of accommodating varied interests. No more. Starting when Newt Gingrich took over as House Speaker, the majority party has monopolized power. As a tactical guide, Gingrich urged followers to study Panzer Leader, the World War II memoirs of Germany’s Col. General Heinz Guderian.

The House is in session only Tuesdays through Thursdays. Members have little time to get to know each other or socialize together. “What they did was destroy the culture of working relationships,” McDermott writes.

Alas, Money, Love and Power slackens off. McDermott spends a (very) long chapter discussing a back and forth legal battle. He was sued by Republican John Boehner after leaking tape of a conversation between GOP leaders on how to “spin” a $300,000 ethics violation penalty against Gingrich. Ex-Speaker Boehner, in his witty memoir, ignores the episode. We also get told in (too great) detail of McDermott’s backstage campaign to get appointed by President Obama as U.S. Ambassador to India.

McDermott ought to devote more space to how members actually get things through Congress. Coverage is often dominated by what Sen. Warren Magnuson used to call “the show horses,” publicity seekers who court Cable TV exposure, the Matt Gaetz-Jim Jordan-Marjorie Taylor Greene crowd. In contrast are “work horses.” In McDermott’s words, “They pull the beer wagon and they are not well known.”

McDermott could be effective. As chair of Ways and Means’ health subcommittee, he oversaw a sweeping revision of foster care in America. The panel’s ranking Republican, Illinois Rep. Jerry Weller, wanted more emphasis on adoption. McDermott fought to extend health care beyond kids’ 18th birthdays.

McDermott championed single-payer health care, marshaling support from 95 Democratic colleagues. A Canadian-style system wasn’t going to fly, however, and McDermott threw his support behind the Affordable Care Act. An hour after its narrow passage, he explained in a phone call that “Obamacare” embraced 70 percent of what he had been fighting for. Millions of uninsured Americans would get coverage, Medicaid would be expanded. No longer could insurers deny coverage to those with pre-existing conditions.

Why demand everything at the risk of coming away with nothing, asked McDermott. The lesson certainly applies to Rep. Pramila Jayapal, his 7th District successor. She has made a splash in the “other” Washington, chairing the House Progressive Caucus, sitting for adoring interviews on CNN and MSNBC, and writing New York Times op-ed pieces on a non-binary offspring and long-ago abortion.

She is less successful as a strategist. House progressives held up passage of a bipartisan Senate infrastructure bill, demanding action on a vast program of social reforms called Build Back Better. The votes were not there in an evenly divided Senate. When infrastructure finally passed, the news was not of major, long-needed projects, but rather feuding Democrats and obstinacy on the left.

McDermott did put himself in harm’s way. “Don’t go!” advised House Speaker Tom Foley when McD informed his Washington colleague that he was taking a trip to Iraq during buildup to Gulf War II. Tracked down in Iraq’s capital by ABC News, he told “This Week” that President Bush (II) would mislead America into war.

He was promptly pilloried on Fox News and called “Baghdad Jim,” decried by neo-conservative warrior pundits, almost none of whom had ever served in the military. In retrospect, despite a questionable choice of venue, McDermott was spot-on.

Money, Love and Power is available through Barnes & Noble and Amazon, costing $18.95, with proceeds to the James McDermott Endowed Scholarship Fund at Seattle University’s Fostering Scholars program. It’s mostly a good read, and heads above staff-written tomes by his former colleagues.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Jim McDermott, one of the most promising of local pols, should never have gone to Congress. We lose a lot of prime talent that way: Derek Kilmer, Adam Smith, Denny Heck. Better for them to pledge only 12 years and then come back to lead the state, as at least Heck has done by becoming lieutenant governor. It’s now a soul-killing job.

IF I have learned anything in the last 8 yrs politically, it is the need for term limits………..Wish SCOTUS could overturn them.