Michael McCarter and his not-so-merry band of southern and eastern Oregon secessionists had high hopes for the Greater Idaho movement. But alas, some voters in the Beaver State didn’t share McCarter’s enthusiasm to pack 860,000 Oregonians and 75 percent of the landmass of Oregon into Idaho, one of the most conservative states in all of the Fruited Plain.

Let’s just say, the momentum for such a draconian way of trying to ameliorate rural angst has been slowed. At least for now. Both Douglas County (57 percent to 43 percent) and Josephine County (54.5 percent to 45.5 percent) voted down measures in the May 17 primary election in Oregon to move their jurisdictions into Idaho.

Klamath County voters, however, supported the idea, (56 percent to 44 percent) meaning nine of the state’s 36 counties so far have voted to at least study this wild-assed notion of adjusting Oregon’s border. The Greater Idaho movement, which in essence means annexing an enormous swath of Oregon, has many mountains to climb.

The Oregon and Idaho legislatures must give it their approval, and it’s hard to see how and why Oregon’s Democratic-controlled House or Senate are going to give their blessing to what is tantamount to a landgrab that will hugely expand Idaho’s territory, diminish Oregon’s wealth, strip the Beaver state of 21 percent of its population, put a damper on political diversity, and give Idaho another seat in Congress.

Also, even the most die-hard supporters of moving the borders have raised concerns that being part of Idaho would entail a significant loss of tax dollars from western Oregon and its rich metropolitan counties, plus a loss of revenue from Oregon’s booming cannabis industry, which remains illegal in Idaho

Then, even if the two legislatures approve of this, the U.S. Congress must also sign off on the new borders, and why would Democrats want to give the GOP additional electoral ammunition?

. . .

Tampering with state borders is serious business. In fact, it has only happened once rarely in U.S. history, including 32 years ago it was, when the Missouri-Nebraska Boundary Compact was formed.

In 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court finally put to rest a land dispute that began in the 1930s when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (“Nature’s orthodontists,” Seattle-based writer Tim Egan called them in his classic Northwest primer, The Good Rain) first tried to stabilize the ever-shifting Missouri River. Siding with Nebraska, the high court ruled that the middle of the river was to be the new dividing line between the two states, except for the sliver of land known as McKissick’s Island.

This Idaho-Oregon effort, though, is far more ambitious and goes straight to the beating heart of the urban/rural divide, which seems to have become increasingly unbridgeable.

And you can blame both political parties for that – Democrats, (progressives in large part) for trumpeting police cutbacks, or in some cases, abolishing police departments altogether; Republicans (right wing extremists, predominantly) with their asinine insistence that the deeply disturbed Donald Trump won the last presidential election.

Over the past two years, the Greater Idaho impetus has mostly scored symbolic victories for its plan to move the vast, sparsely populated rural areas of southern and eastern Oregon into the Gem State. Baker, Grant, Harney, Jefferson, Lake, Malheur, Sherman and Union counties have approved measures directing officials to look into the border changes. Wallowa County, which has already given a thumbs down to the border alteration, will vote on the subject again in November, as will Morrow County.

. . .

The man at the forefront of all this is a retired agricultural nurseryman named Michael McCarter. Last summer, on a late Saturday morning already so hot in downtown Boise that even a report-to-hell order from Gov. Brad Little may have offered Idahoans some relief, McCarter tucked himself into a cozy chair inside the elegant lobby of The Grove Hotel and began his well-practiced sermon on why a hugely inflated Idaho is a good thing.

“What we have here is a battle between traditional values and urban values,” McCarter, president of Citizens for Greater Idaho, told me. “The urbanites don’t have the same attachment to their community. When was the last time you saw a block party in an urban area?”

“Ummm, yesterday,” I replied.

McCarter smiled and went on, unruffled. He is a pleasant man of 75, soft-spoken, spry and whip smart. For the past 26 years, he and his wife Pat have lived six miles outside of La Pine, a small rugged high-desert town in Central Oregon that lies in the shadows of Mount Batchelor.

A self-described sports nut who “came to the Lord” in Salem 40 years ago, McCarter has been married four times. Wife No. 3, Susan, left him for another man, a Utah Mormon and convicted child molester. Pat, his current wife, played piano at his church in Salem Heights when they met. “We dated for two years before we kissed,” he confided.

In the La Pine area, McCarter hunts deer, black bear and elk, sometimes in four-feet of snow. (Elk meat, he claims “is a step-up from filet mignon.” McCarter does, however, draw the line when it comes to eating wolf.)

And so, McCarter tries another tack: “Urban people are not attendant to the land. They sell it and move on; they have a much more transient lifestyle.”

I asked him to define the traditional values that he holds so dear.

“Faith, family and freedom,” McCarter answers, rattling the 3 ‘F’s off faster than Lilly, his five-year-old black squirrel-chasing Labrador can race through the Jack pines and ponderosas that clot his two-acres of land.

“There was a big ice storm in Portland last winter, and this guy gets stranded and he tells me no one came to help. But in rural Oregon, we have generators, pellet stoves, wood stoves. We are independent. We don’t have to rely on government. We have to turn-off the Portland spigot.”

I don’t have the heart, and lack the inclination to tell McCarter that I have actually seen generators and wood stoves at work in Seattle.

McCarter goes on. “The urban person looks at the rural person as being lower class, a hillbilly, a white supremacist redneck.”

He recalls his youth, growing up in Portland’s suburbs, near Gresham, his parents of blue-collar stock, both Roosevelt Democrats.

. . .

McCarter supported Sarah Palin’s VP bid in 2008, but admitted he was no fan of John McCain or Mitt Romney, the GOP standard bearer four years later. He said he admires Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, as well as former governors Mike Huckabee and Rick Perry. But he gets tongue-tied when it comes to Trump.

Let’s hear him out, though:

“My closest hunting buddy is an anti-Trumper and I’m a pro-Trumper. Do I wish he’d go on saying what he’s saying? No. But I go on what they do, not what they say.”

“So, Mike, who did win the election?” I asked.

Again:

“I agree with the seventeen states who have tried to tighten up their voting standards.”

One hates to embarrass this man, because you grow to like him, whether or not you agree, and you come close to tears when he tells you of the baby who lived just two days, or that for more than 20 years, he has suffered from a relatively rare disease called hemochromatosis, which means he has too much iron in his blood and needs to head 25 miles down to Bend every two months to see his oncologist and shed some blood.

“People,” McCarter added, gaining his composure from my abbreviated Trump interrogation, “misunderstand the movement. The media goes on and on that we are secessionists. No, we are not trying to secede but only to start a discussion.

“You know, in 2016, remember Ben Carson, the black brain surgeon, saying he didn’t think Trump had a chance. Well, why can’t we win this too?”

McCarter said the ballot initiatives are non-binding, and besides, he and his fellow volunteers are pursuing them only to highlight rural discontent.

“It is really just a peaceful revolution. Look, I’m pretty sure a lot of urbanites would say, ‘Let ‘em go, and don’t let the door hit them in the ass on the way out.’”

. . .

The idea of secession has certainly gained traction among many rural Oregonians, and even some of its political leaders.

“When I was in the Legislature, I was always jumping up and down about the urban/rural divide,” Josephine County commissioner and former Oregon Senate minority leader Herman Baertschiger Jr. told The Oregonian last year. “It’s two very different lifestyles, two different ways of life.”

Ken Kesey’s 1964 novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, painted an unforgettable portrait of a hard-headed family of Oregon Coast Range loggers, who lived by the motto: “Never give an inch.”

The novel, often called the greatest Oregon book of all time, raised the fear that rural ways were vanishing in much the same way the state’s timber industry went into full retreat, and that they may never return.

In La Pine, where McCarter lives, signs plastered to pine trees, abandoned shacks, and to vacant storefronts remain which read: “Blue Lives Matter,” and “Don’t Blame Me, I Voted for Trump.”

As an elderly man, who used to do maintenance work at the Odell Lake Lodge & Resort, told me, “In these parts, people don’t give a rat’s petunia for transgender rights, and don’t get ‘em going, neither, about defunding the damn police.”

Amanda Wallace, a resident of Deschutes County, summed up what many disenfranchised rural Oregonians are feeling, when she told The Oregonian: “Conservatives don’t feel like their voices are heard in Oregon. Sadly, Portland, Salem and Eugene make all the decisions.

Still, not everyone in these parts is gung-ho about turning over hundreds of thousands of Oregon acreage to Idaho. “The devil is in the details, and the devil is also in hard realities,” wrote Charles Jones, a science teacher and resident of LaGrande in eastern Oregon.

In an op-ed piece published last year in the Baker City Herald, Jones asked, “Will Oregon donate millions of dollars of (snow) plows to another state? Who will keep our highways clear?” Jones also wondered whether Idaho intended to assume full costs of maintaining prisons in eastern and southern Oregon, or ante up to build trails and the like in its state parks, not to mention servicing the debt on millions of dollars in bonds issued for dozens of construction projects in rural Oregon.

“And this is only the tip of this devilish iceberg,” wrote Jones, a retired Navy commander.

. . .

Ever since South Carolina became the first state to secede from the union in November of 1860, the idea of separating oneself from one’s government and forging anew has animated some Americans.

The American Revolution was the ultimate act of secession. When Barack Obama was president, the governor of Texas talked vaguely about the state’s right to the leave the union. After Trump’s victory in 2016, people talked of California’s exit.

Not long after the ink had dried on the Declaration of Independence, Appalachian settlements in Kentucky and Tennessee expressed grave doubts about remaining with their eastern brethren and formed separatist movements, noted Richard Kreitner in his 2020 book, Break It Up: Secession, Division and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union.

When I was a young boy growing up in the Bay Area in the early 1960s, back when San Francisco, believe it or not, elected a Republican named George Christopher as its mayor, my father would share conversations over the dinner table that he’d had at work about Northern California becoming a separate state.

And it wasn’t because we hated the Dodgers, though we passionately did. No, then, it was over water rights and, more importantly, Northern Californians’ strong feeling of superiority over its southern neighbors.

Of course, that was a time in which Southern California, particularly Orange County, voted heavily Republican, a key reason Richard Nixon carried the state, though barely, in 1960, and where Ronald Reagan would follow suit six years later in his gubernatorial race against Pat Brown.

Even today, serious chatter persists about chopping up the Golden State to create as many six different Californias.

. . .

McCarter is at the wheel as we head to Garden City, known for its cluster of craft breweries and winery tasting rooms along lively Chinden Boulevard near Boise, to attend a pep rally for the Move Oregon’s Border movement.

The rally is sponsored by the Powderhaus Brewery, a big Trump financial booster in both 2016 and 2020, located next to the Bella Vista Funeral Home, where a couple stand in the shade eating a hot dog.

A large “Move Oregon’s Border” banner hangs outside. With the temperature showing an epic 106 degrees on this July afternoon, one might have expected a much larger crowd than the 20 or so people who’ve showed up to bask for an hour or so in air-conditioned comfort.

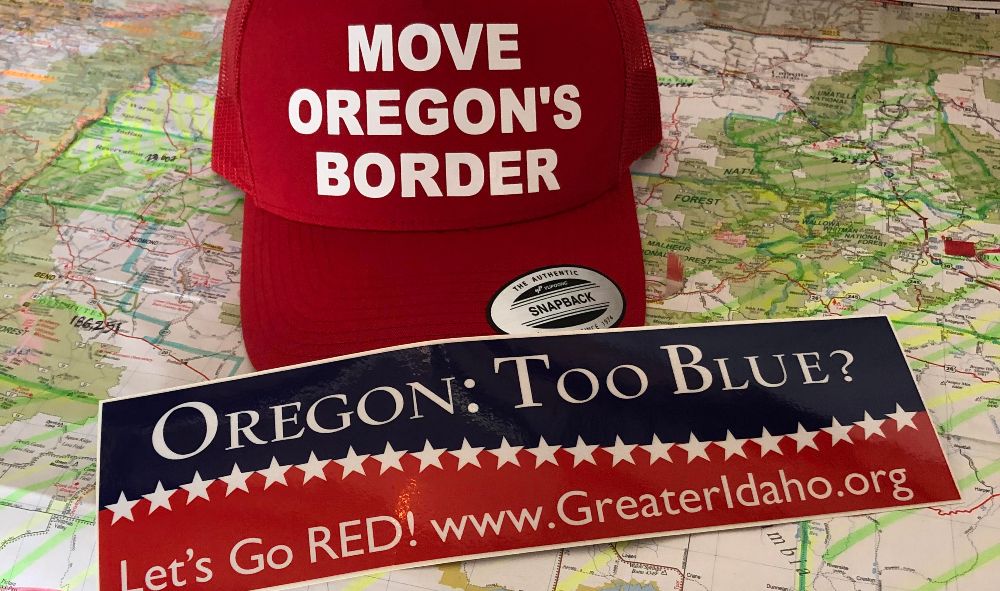

Tables are set, laden with T-shirts that read: “Don’t Tread on Ale,” and bright red and blue bumper stickers, with the message: “Oregon: Too Blue?” And, beneath it, “Let’s Go RED! advertising GreaterIdaho.org.

Keaton Ems, a 31-year-old eastern Oregon Christmas tree farmer and secretary of Citizens for Greater Idaho, put the rally together and is milling about the brewery waiting for the speeches to commence.

A tall, lanky man, with a well-trimmed beard, Ems declared, “People on the left are more authoritative than people on the right.” He went on to maintain that rural folks are somehow better people than urbanites.

“In Portland you had firebombs for one-hundred consecutive nights. People moving out. Feces on MLK (Boulevard). Graffiti everywhere. Trash. All of this versus rural areas, where people are cleaner, more forgiving and have a better sense of where they want to go,” Ems said.

“Trump stood up for us against the establishment and the deep state interests.”

Just before jumping on a makeshift stage to rally the troops, what few troops there were, former Oregon House Speaker Mark Simmons stood beneath of a 14-foot-high steel tank container, with 900 gallons of beer inside, and told me, “This border proposal is only one answer to the urban/rural divide.

“You know, we all lose when we can’t listen to each other.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Demeaning comments regarding Michael McCarthy detract from your article. I grew up in Eastern Washington and the “Cascade Curtain” will always exist. There are, as a general rule, different values in urban and rural areas.

Had the “State Map Drawers” thought more critically, the boundary would not have been the Columbia River but the Cascade Mountains. Then we would have two States – one primarily rural, one urban. But then there would be no need for articles like this.

Different values is one thing, different reality is another. Maybe the complement to this article should be one that goes into Seattleite’s misguided ideas about our fellow Washingtonians across the mountains, and about whatever political delusions we may be suffering under. But there isn’t anyone obvious to interview, that I can think of – who’s dedicated his or her energies to jettisoning the east side.

Dear Ellis Conklin,

Please update the election results you cited. The final results were announced this week:

Douglas County 47% in favor

Josephine County 49% in favor

Douglas County 57% in favor

This is much different from the early results you cited in your article. The sources of the new numbers are linked in this release: https://www.greateridaho.org/greater-idaho-movement-changes-proposal-map/

State borders have been shifted dozens of times in US history, most recently in 1999. For sources, read the first 2 pages of this pdf: https://www.greateridaho.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Greater-Idaho-Proposal-r22.pdf

The Oregon Legislature has good reason to agree to moving the border. We list them on the homepage of greateridaho.org

We do really want to move the border.

I’m reminded of the two political realities in the state of Washington. One can be seen from the top of the Space Needle, and the other from the top of Mount Rainier. The big mistake the state GOP made was to stop nurturing and supporting King County Republicans, who would have made a big difference in the Olympia caucuses had they survived.

Fascinating story, Ellis. Haven’t heard too much up here in Seattle about that. It’s truly another world out there. Years ago I almost took a newspaper job in Greater Idaho. It sounded great, I’d be the editor of a publication in what is the county seat and biggest city in an area of incredible scenic beauty, as it is in much of Greater Idaho. Then I checked on the city’s population, and was shocked that it only had a few hundred more people than the number of students in my high school in Seattle. Figured it was a typo. That didn’t scare me away as much as the remoteness, I’ve worked in small towns before and enjoyed it. But they were easy to get to. Not this town. The closest airport with commercial flights, whoops, make that one commercial flight a day, was more than two hours away in often very hazardous driving conditions and then it would take two flights to get to Seattle instead of one, thanks to airline deregulation. But that’s another story. Maybe you can tackle that one sometime. Thanks again for this story.

I meant to say Lesser Seattle. Ha. Keep up the great work, Ellis!

One of the ironies of Mr. McCarter is his line about “do urbanites have block parties.” And while it is true, we have many, we also realize patriotism is about community not individual “rights.” If you look at the COVID vaccination rates of urban areas v. rural, the rebellion against mask mandates in rural areas, the idea that anyone can and should own multiple guns to “protect themselves,” I would hazard to say urbanites are more about “traditional” American values: sacrifice for community, shared responsibilities, and a belief that community “government” works for all of us. These are gross generalizations of course, but the sense of “victimhood” that many rural folks have (and the NYT loves to emphasize) and the “you urbanites don’t understand us” belies the fact many rural folks also “look down on” everyone who “isn’t them.” Mr. McCarter has this idea that he lives in some Amish community where everyone helps at the barn raising when in fact, no one will lift their arm to get a COVID shot to protect him from his immune issues with his chronic blood issue.

People of Oregon deserve someone who pays his bills and supports his country -not a two bit mobster from Queens who is a draft dodger and deadbeat like like Donald Trump who has never made a promise he doesn’t break or business he does leave destroyed in his wake of malevolence and incompetence.

As a long time Oregonian and one living in the rural area of the state I can tell you not all of us want the borders to move. I have visited both Portland and Salem and have never had anyone say anything against the rural parts of the state, never had anyone say anything against me about being from a rural area. While there may be different political views I have seen flags and signs for both sides of the political isle in all parts of Oregon. I say leave the border alone as not all of any county has voted for it so there will be people forced into this against their will if it happens.