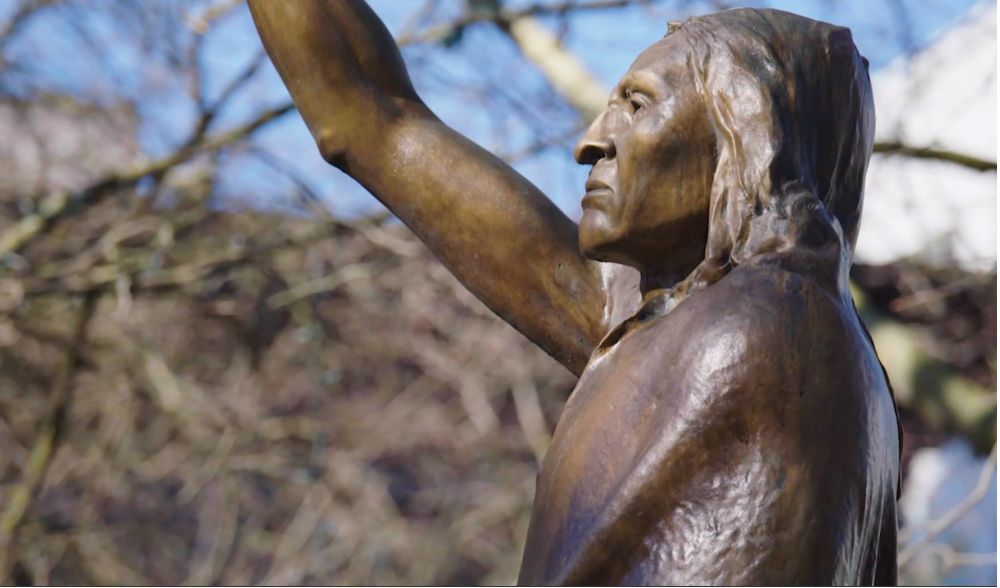

Seattle may be named for Chief Seattle, but his presence (and that of his people) is difficult to detect in the modern city. One example is the portrait of Chief Seattle just inside Pioneer Hall’s front door in Madison Park, one that is based on an image made in the 1860s by E.M. Sammis.

Other photos of that famous image were also taken, and in at least one version of this famous portrait, the Chief’s eyes, which were closed, are altered so that he is staring directly into the camera lens (or the painter’s easel). What was the Chief thinking as he sat quietly in the simple straight-back wooden chair?

When gazing on this large, colorful painting of Chief Seattle, I ponder what the old man had seen during his life – and what he might be thinking about his largely dishonored people today.

When the old Chief sat for this photograph, a decade had passed since he attended the fateful 1855 Treaty meeting at Point Elliott, so he had ample time to consider the results of that gathering. In January 1855, Isaac I. Stevens, Governor of Washington Territory, presided over a meeting at Point Elliott, also known as Muckle-te-oh, today’s Mukilteo. (The Indian name originally meant “good camping ground.”)

Stevens had done his homework. He arrived with a small contingent of Indian Agents, including Michael Simmons, U.S. Army officers, and interpreters. The Indian nations sent several hundred people representing virtually all the Salish Sea native villages from the Canadian border to Lower Puget Sound.

Barely understanding Gov. Stevens’s proposals, Chief Seattle and his colleagues nevertheless signed the treaty on January 22, 1855. Article 1 described how the Indians had to “cede, relinquish and convey” to the United States virtually all their aboriginal land. Articles 2 and 3 outlined the small reserves, including Port Madison, Nooksack, Lummi, Tulalip Bay, and the Snohomish River, that were “given” to the Indians.

Other articles listed gifts and assistance promised to the tribes from the U.S. government. They also described behavior (“free all slaves,” no “ardent spirits,” a promise to “be friendly” with all [non] Indians, etc). Perhaps the most demeaning of these statements was the provision that signatory tribes and bands “acknowledge their dependence on the Government of the United States.”

Despite this historic, and what to the Indians must have been a dispiriting event in 1855, on Sunday, August 22, 2010, a “Descendants Committee of Seattle,” sponsored by Seattle’s Museum of History & Industry, hosted a “Return to Muckle-te-oh” anniversary of the signing of the Point Elliott Treaty. The ceremony was held at Lighthouse Park, Mukilteo.

There was not a lot for Natives to celebrate, for today the Duwamish Tribe (Chief Seattle’s clan) has not been given an adequate reservation, nor is it allowed to fish its ancestral waters when it wishes, as other tribes have won by long legal struggles. Further, the Tribe is still not recognized by the federal government.

The question of “non-recognition” is complex, and few figures in authority want to untangle the issues. If an American Native group maintains continuous records of its meetings, festivals, programs, and leadership, the Department of Interior can, after official recognition, provide land, scholarships, medical and administrative support to that group.

This predicament is illustrated in the case of two local Native groups, the Chinook (Columbia River) and the Duwamish (Seattle), despite their long association with and assistance to Euro-American settlers, seamen, explorers, and fur traders. For a period of time (under the Obama administration) the Chinook were headed for recognition. The following administration of George W. Bush reversed that decision because it perceived that records of the Chinook people were confusing and no continuing leadership had been shown.

The Duwamish, despite several hundred years of mixing (and inter-marrying) with settlers, hiring lobbyists, and demonstrating their traditions and history to all, did not satisfy the record-keeping requirements of the Department of Interior and so remain unrecognized (in many meanings of the term) to this day.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Failure to recognize and provide Tribal assistance: deplorable. Come on Biden, while you still have an Office anda Native American Interior Chief.

This is largely about politics,and shameful that Tribes who “got” won’t let others have their recognition.

What is tragic is that other Tribes are often the ones fighting against the recognition. They fear their slice of the pie will be smaller. Or that people won’t frequent their casinos if another Tribe’s casino gets built, after the currently unrecognized Tribe gets full recognition. With recognition, and land, comes the right to do their own economic development, which includes, among other things, natural resource access and the ability to build a casino. And casinos have brought wealth to many Tribes.

I’ve been curious about the TV ad campaign the Muckleshoot Tribe has been engaging the past year. They make the claim that they are descendents of the Duwamish People, and end with, “We are Muckleshoot”. Is this to raise awareness of the Muckleshoot? Or to squash the claims of the Duwamish Tribe?

I confess I was left a little dizzy when I read (toward the end of the article) that George W. Bush overruled a decision of the Obama administration. Was Bush elected for a third term that I somehow missed?

Yeah, that caught my eye too.