March 2022 marks 30 years since one of the most dramatic political crash-and-burn spectacles in Northwest history. It’s a scandal worth recalling now because we live with—benefit from—its legacy. From it flowed a cascade of effects that brought about a remarkable and under-appreciated rise of women into elected office in Washington, a political ascendancy unmatched in any other state.

If that last seems over the top, consider. Washington had never elected a woman to the U.S. Senate until 1992, when Patty Murray came out of nowhere. She and Maria Cantwell now have held both the state’s U.S. Senate seats for the past two decades, their run rivalled only by California’s Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, both also first elected in 1992. Meanwhile, 23 states have never elected a woman to the Senate.

In the House, Washington since statehood has been represented by a total of 98 individuals, only three of them women, prior to 1992. Two more were newly elected that year—Jennifer Dunn and Maria Cantwell—and Jolene Unsoeld was re-elected. Today, with the 2020 election of Marilyn Strickland (the first African-American to represent Washington in the House), women hold six of the state’s ten House seats. Washington is the only populous state where women make up a majority of the House delegation.

Washington voters had occasionally elected a woman secretary of state or superintendent of public instruction before 1992. Women that year won four of Olympia’s eight statewide elected offices, including the powerful post of attorney general, which Chris Gregoire took, positioning herself to become governor 12 years later.

Since 1992, the number of women serving in the Washington legislature has increased by almost one-third, to slightly more than 40 percent of the total–less than in a few other states, but a significant advance, nonetheless. And until Jenny Durkan stepped down as mayor of Seattle at the end of 2021, the state’s seven largest cities all had women mayors.

As the fate of American democracy seems to teeter on a knife edge these days, it’s refreshing, if not entirely reassuring, to take stock of the dramatic broadening of political representation that began not that long ago, especially in Washington but also nationally. Much of it can be traced to the elections of 1992.

What made that year a watershed? Second-wave feminism played a role. So did the Senate’s handling, during televised confirmation hearings in October 1991, of Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment by Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas.

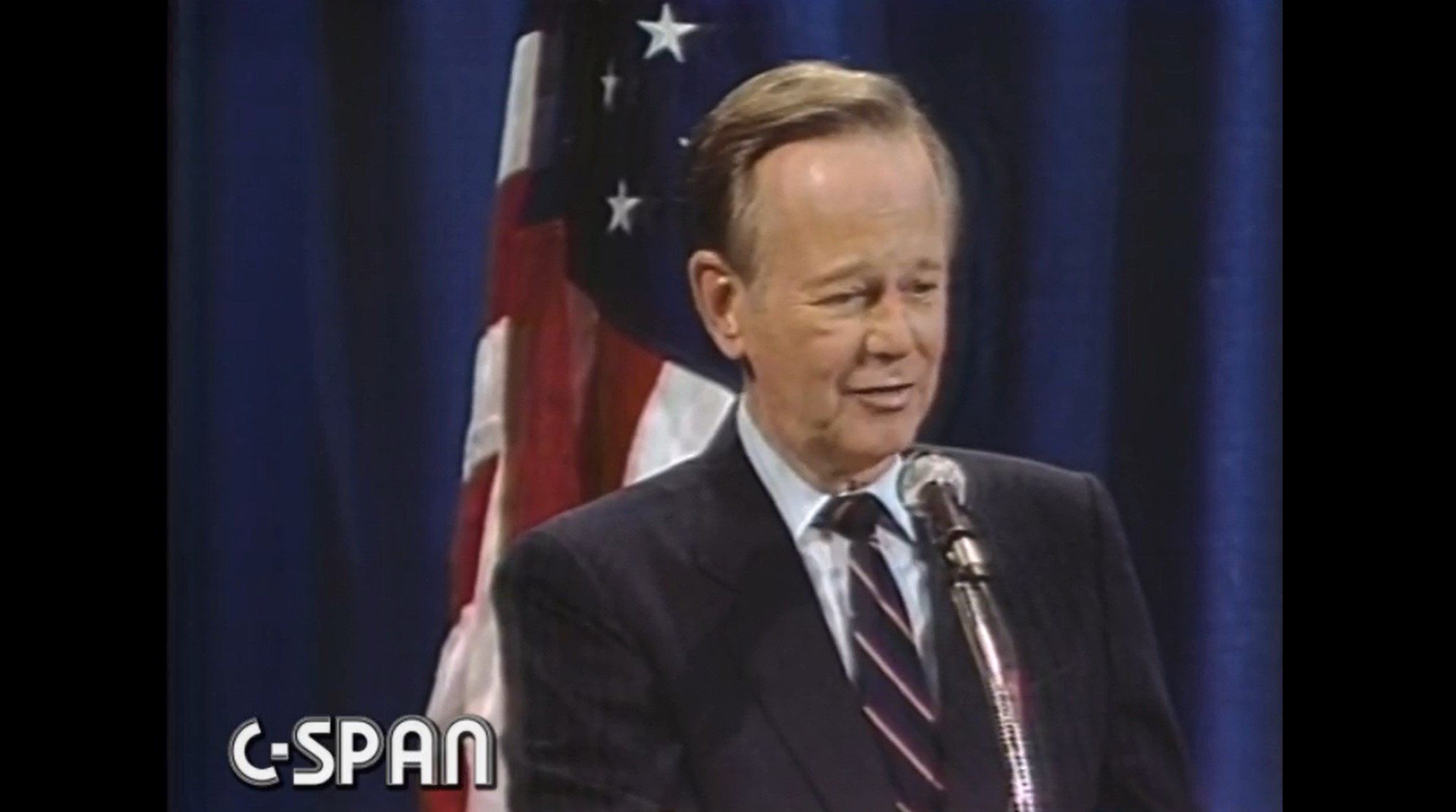

In addition, Washington women had a special reason to become politically engaged and voters to welcome them as outsider candidates. The provocation was the March 1992 downfall of Washington’s senior U.S. senator, Brock Adams. Therein lies a tale that illustrates how much politics has changed in 30 years, and yet—thinking of Andrew Cuomo, here—how little.

The Dark Side of the Pillsbury Doughboy

On March 1, 1992, The Seattle Times published a blockbuster exposé, spread across five full pages, that unleashed an avalanche of accusations against Adams from eight unidentified women. The incidents they related were spread out in time over many years—tales of sexual harassment, abuse, and a rape. Adams immediately shut down his campaign for re-election that November.

The story’s genesis was precisely five years earlier, on a balmy spring evening in Washington, D.C., when Kari Lynn Tupper, a 24-year-old staffer for a committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, visited Adams in his home. Adams was newly elected to the Senate after a dozen years in the House from Seattle’s seventh district, and he was a close and long-time friend of Tupper’s parents.

As she later told police, she had two drinks with Adams, then went to the bathroom and suddenly felt dizzy. She woke up in a strange bed, nude or nearly so. “I was completely confused,” she recalled, as the 60-year-old Adams lay by her side, fondling her breasts and buttocks and trying to kiss her. “I started crying. When I figured out who he was, I couldn’t figure out how it happened.”

The incident did not come to light for 18 months, and then only because Adams, mistakenly thinking Tupper was about to go public with her account of the evening, tried to upstage her with his denials. When she did speak out, the ensuing controversy did not end Adams’ political career.

Tupper’s allegations were so shocking, the actions she described so outrageous, they beggared belief. No one else during Adams’ three decades of public life had ever charged him with anything much worse than goofiness. He had a gee-whiz ebullience that led The Washington Post to label him “the Pillsbury Doughboy of Puget Sound Politics,” hard to picture as a predator.

The Democratic party stood by him. So did most women’s groups, who noted his reliable support for their issues. During the remaining four years of his term, Adams repaid their loyalty and tried to repair his image by displaying a new-found interest in women’s health.

The Tupper controversy faded. But The Seattle Times soon realized Tupper was not, as she seemed, Adams’ lone accuser.

The Times was contacted by a second woman, an aide to another Democratic member of Congress. She met with an editor and a reporter in the far back corner of a Seattle bar. Tearfully, this other woman recounted an experience much like Tupper’s: an invitation for career counseling, a cocktail, a foggy awakening in Adams’ bed—she nude, he on top of her. It had happened to her two weeks after it happened to Tupper.

This woman would not speak publicly. She had witnessed Tupper’s torment in the media spotlight and knew that joining her there would damage if not end her own career on the Hill. Her purpose was to urge the Times on. “I know Kari’s telling the truth,” she said. “Please keep digging.”

The digging continued, off and on, for more than three years. Three Times reporters and David Boardman, then city editor, eventually talked with a dozen women who said they had been sexually assaulted or aggressively harassed by Adams. “All told compelling stories whose verifiable details—dates, schedules, locations—checked out,” Boardman recalled later. “All provided contemporaneous corroboration, friends or relatives they had told of the incidents shortly after they occurred.”

In hindsight, the privilege and silence that had been accorded Adams are striking. His caddish conduct—and worse—was widely known on the Hill. “We referred to it as `Brock’s problem,’” his long-time secretary told the Times. “Everybody did.”

Yet as damning as it was, what “everybody” knew about Adams was considered unfit to print for a long time after The Seattle Times knew it, because none of the dozen women other than Tupper who accused him of misconduct would agree to be named in print or even identified to the senator.

Most were embarrassed and humiliated by what had happened to them. They had jobs and reputations to protect. They were discouraged by how little impact Tupper made after Adams shoved her into the spotlight. And their resolve to stay out of it only strengthened in 1991 when Anita Hill went before the Senate Judiciary Committee—made up of 14 white males—and endured questioning that was by turns irrelevant, patronizing, and hostile, after which Clarence Thomas was handed a lifetime appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court.

With no one willing to go on the record, Washington state’s largest newspaper faced an excruciating dilemma.

“As 1992 dawned,” Boardman wrote later, “we in the newsroom faced this reality: We could publicly accuse a U.S. senator of being a sexual predator, without telling him the names of his alleged victims—a course that on its face seemed preposterous. Or we could allow him to be re-elected, even as our reporting had convinced us of his offenses.”

Adams’ re-election was by no means assured–polls indicated that Tupper’s accusations had damaged him–but when he signaled his intention to run, he raised the stakes for the Times, and it hit upon a legally and ethically defensible way forward. The senator launched his campaign on February 13. Two weeks later, the newspaper reported the allegations of eight unidentified women who, the Times said, agreed to sign statements affirming they spoke truthfully and acknowledging they might have to face Adams in court if he sued the newspaper.

“This is the saddest day of my life,” Adams said a few hours later at a news conference where he announced he was ending his re-election campaign. “I have never harmed anyone,” he said. “That was an article that was created out of whole cloth by people that hate me, and I don’t know why they do.”

Despite calls for his resignation, Adams served out the remaining 10 months of his term, continuing to insist on his innocence. He and his wife, who stood by him throughout, retired to the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Adams developed Parkinson’s disease and died of its complications in 2004.

“Dang Me, Dang Me”

Adams’ flame-out improved Democrats’ chances of retaining his seat, and several prominent Democrats seemed eager to fill it. The most likely contender was a former congressman, Mike Lowry, a favorite of liberals, who was quick to point out that he almost beat Slade Gorton for the state’s other Senate seat four years earlier. (That narrow victory was a return to the Senate for Gorton, the Republican incumbent whom Adams defeated in 1986.)

Another former U.S. House member from Washington, Don Bonker, was interested. And speculation focused especially on the state’s moderate governor, Booth Gardner, who had said he would not seek a third term in 1992.

Any of these potential Senate nominees was expected to be able to bigfoot the only Democrat who had dared provoke Adams’ ire by formally entering the race before he exited it.

This interloper was Patty Murray, whom political pros and journalists casually dismissed. Her résumé was thin, its highlights being her service on the Shoreline school board and one term as a Washington state senator “who’s not been especially dazzling,” wrote a Seattle Times columnist, Richard Larsen.

Murray was little known outside her district and easily overlooked—barely five feet tall, with what another Times writer, Joni Balter, characterized as a “sometimes whiny voice” that “cracked with emotion and tension during debates and campaign appearances, making her sound weak and ineffective.”

If Murray’s vocal talents were limited, she turned out to have great instincts, discipline, timing, and luck. The luck came early. In the two months after Brock Adams’ retirement announcement, Mike Lowry and Booth Gardner each dropped out of contention to replace him, Gardner to make good on his announced plans to retire and Lowry to try to succeed Gardner as governor. (Lowry was elected governor, only to end his political career under a cloud four years later, accused of sexually harassing his deputy press secretary.)

Murray made her own luck, too, with a tightly focused message that posed her inexperience as a virtue. She shrugged off consultants’ entreaties to become more conversant on issues, to maybe read The New York Times regularly.

Instead, she branded herself—repetitively, to the point of drawing ridicule—as a “mom in tennis shoes,” a label she said a dismissive legislator once put on her when Murray went to the state capitol as a parent to protest cuts in funding for a local pre-school program. Unlike incumbents of his kind, her mantra went, she shared the everyday concerns of families, of outsiders like herself, and of women, particularly women appalled that, of 100 U.S. senators, only two were women, and this was the most there had ever been.

“Murray’s attacks on the ‘blue suits’ paint all male politicians with the same broad brush,” complained yet another Seattle Times columnist, Ross Anderson. “Meanwhile, Murray hasn’t given us a clue what she would contribute to the Senate beyond gender.”

Yet, her strategy resonated in the moment. Adams’ offenses were a fitting prelude, of course, and other headline-grabbing developments also harmonized. Days after Adams called it quits, the House banking scandal broke, revealing that arrogant self-indulgence was bicameral. Dozens of representatives were in the habit of writing bad checks with impunity, courtesy of the House Bank, and some exploited the bank’s lax controls to commit serious crimes. Four ex-members were convicted on bribery, corruption, and conspiracy charges.

All of the worst check kiters, like 94 percent of House members at the time, were men. Exposure of their good-old-boy sleaze fed the frustration that many voters had been feeling since the previous autumn, when the Senate manhandled Anita Hill. Those hearings were what originally inspired Murray to run for Senate, she said—and said, and said.

Those hearings were a touchstone also for EMILY’s List, to which Murray’s name was added early in the primary campaign. Formed in 1985 to help raise campaign funds for pro-choice Democratic women, EMILY’s List grew slowly and had little to show for its efforts until 1992, when the accumulation of male outrages sparked a seven-fold increase in the number of List donors, who contributed a record $10.2 million to campaigns. A total of $150,000 went to Murray before the primary, boosting her credibility.

The mom in tennis shoes sprinted past Don Bonker in the primary to go up against the Republican nominee, Rod Chandler, a five-term congressman from King County’s Eastside suburbs, who could not have been more of a contrast with Murray. A polished former TV news anchor, he was as vague about why he was running as she was repetitive.

And his theory of the case was the opposite of Murray’s, such that his message inadvertently reinforced hers. “Patty Murray’s just not ready,” his ads proclaimed, verifying her outsider credentials with a paternalistic pat on the head, and doing so prominently, as Chandler outspent Murray two-to-one.

The Republican made things immeasurably worse for himself with a bewildering display of jerkiness at a crucial moment. During a televised debate two weeks before election day, Chandler responded to Murray’s criticism of his record by launching into the lyrics of a 1964 country-western song by Roger Miller:

Dang me, dang me,

They oughta take a rope and hang me,

High from the highest tree.

Woman, would you weep for me?

Murray looked perplexed but did not sound that way. She said, “That’s just the kind of attitude that got me into this race, Rod.”

Bob Packwood, Diarist

The vote was not close—54 to 46 percent. Patty Murray was elected Washington state’s first female U.S. senator. A day later, she took a congratulatory call from Anita Hill.

Murray’s win was part of a wave. When the Senate reconvened, its two women members were joined by four more, including Murray and Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, the first Black woman elected to the Senate. California became the first state to have two women U.S. senators at the same time, electing former San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein and five-term congresswoman Barbara Boxer on the same ballot.

In the House, the number of women increased by two-thirds, from 27 to 45. They remained a tiny minority in each chamber, but the trend was dramatic enough to prompt headlines declaring 1992 the year of the woman.

As if to validate the trend, allegations of gross sexual misconduct surfaced during the final weeks of the year against two newly re-elected Senate lions. One was Hawaii’s Daniel Inouye, whom The Honolulu Advertiser reported was accused by his former hair stylist of pressuring her into having sex 17 years before. A state lawmaker said nine other women told her they too were sexually assaulted or harassed by Inouye.

He denied the allegations, which made his life “a living hell,” he said, although the heat on him did not last long. His accusers declined to participate in an inquiry by the Senate Ethics Committee, which quickly dropped the matter. Inouye remained in the Senate for another two decades, until his death.

Better substantiated and more consequential was the sex scandal that engulfed Oregon’s Bob Packwood only 19 days after he won his fifth Senate term. Humiliatingly scooping The Oregonian, The Washington Post published allegations of ten women—mostly former staffers and lobbyists, identified by name—who said Packwood had sexually abused and assaulted them. Eventually, 19 women came forward with similar tales of crude harassment and worse.

Packwood denied any wrongdoing and brushed off calls for his resignation, but it came to light that he had kept a diary of some 10,000-plus pages, the contents of which could be self-incriminating, the senator acknowledged. He initially refused to hand the diary over to Senate investigators, then shared some of it, but was discovered to have edited out references to his sexual encounters. Defiant, he seemed to threaten to expose wrongdoing by other members of Congress if they continued to pester him.

This went on for three years before the Senate Ethics Committee recommended Packwood’s expulsion on charges of sexual misconduct and obstruction of justice. He resigned the next morning, checked into a clinic in Minnesota for alcoholism treatment, and went on to a lucrative career as a D.C. lobbyist.

Oregon’s lengthy ordeal with Packwood, closely observed north of the Columbia River, added to the dramatic effects of the Anita Hill hearings, Brock Adams’ outrages, and Patty Murray’s out-of-nowhere victory on electoral politics in Washington state.

Beginning 30 years ago, arguably in this state more than anywhere else, women were provoked, inspired, and galvanized to jump into the political arena and eventually assume power. Which raises the question: What difference have they made?

Teasing out an answer would be a difficult and treacherous exercise in alternative history, requiring an ability to discern what things would be like if women had never stepped up. Maybe the more appropriate question is this: How is it possible that, until a few decades ago, most Americans seemed to accept the legitimacy of a supposedly democratic government that excluded women–and not only them–from full participation?

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“What difference have they made?”

Great question. Downtown Seattle sure has changed over the past 30 years. Statewide both social, economic, and racial inequities are much more pronounced. The quality of political discourse here has become far less nuanced and it’s much coarser.

Seems like Adams’ despicable conduct may caused this state’s Democrats to overreact by purging and marginalizing white hetero males, as if that were a noble goal. The party has been backing exclusively women, gay men, racial minorities, and (for lack of a better term) “beta” white males like Constantine, Strauss, McKenna, Ferguson, etc. That’s new, and a tactic not seen elsewhere.

Patty Murray’s success benefitted from an unusual confluence of events. Not least of them was her pluck and determination. She entered the race right after the Anita Hill mishandling, before the Adams scandal got underway. Nationally it was becoming the year of the woman: voters fed up with treatment of women, with congressional chicanery and white male entitlement. The Seattle Times handling of the Adams scandal, long hard slogging by dedicated reporters, led by Editor Dave Boardman forced Adams decision not to run. But it still was identity politics. Who would you rather have represent you, an earnest hard worker like Patty or a dismissive guy like Chandler?

Great informative article! Electing women does make a difference by bringing fresh insights and experiences to the political mix. We’ve seen this in legislating on issues like family leave, education, reproductive justice, sexual assault, gun control and much more. But we still need to get more women and more diverse women to run for office.

Thank you for writing this. I am old enough to remember those scandals and the “year of the woman.” But I often wonder if younger women realize that the “Me Too” movement isn’t a new phenomenon.

Congratulations to Senator Murray on 30 years in the Senate. Along with Senator Cantwell, Washington has a one-two punch that rivals Maggie and Scoop.

Not to exonerate Brock Adams, but it is worth noting that he was the last time Seattle’s liberal downtown lawyers sent one of their own to Congress. Since the Fall of Brock, that lawyer group has lost clout. Some firms are now owned by large national firms, and those two toxic words, “Seattle” and “downtown” have lost their electoral gloss. Also, liberals are badly split into the moderate and radical factions. To be sure, Jim McDermott had genuine ties with this group, as did former Rep. Norm Dicks. Warren Magnuson also had deep ties to the gang that used to rule Seattle’s moderately liberal roost. That Fall of Brock pretty much ended Seattle’s old political sway, not just the rule of males.

Adams’ crash-and-burn did not end the problems caused by a relative handful of self-interested Seattle lawyers shaping unique policies here. Those 3-4 law firms remain the source of many local politicians, including Jamie Pedersen, John McKay, Rod Dembowski, Rob McKenna, Bob Ferguson, Nicholas Brown, and innumerable judges. In addition, Gary Locke, Mike McKay, John McKay and others joined those law firms after their stints in office.

It was by total coincidence that on the same day that I read this, that I read about the passing of Deborah Senn, who was every bit a part of that political shake up. She was elected as the first woman to serve as Washington Insurance Commissioner.

Thanks for acknowledging Deb Senn’s election in that important 1992 watershed year. She worked tirelessly for “the little guy” in the face of big insurers and the legal/regulatory framework that had been built for the industry under the eyes of previous commissioners and generally compliant legislators. Mr. Mitzman’s account of Adam’s scrofulous fall and the monumental changes of 1992 was a high mark in Washington State’s journalism, possible only because the Times was sufficiently well financed to face the possibility of a costly legal fight. I ran the State Democratic Party’s field campaign that year and vividly remember how top Party insiders were backing Bonker. As I had worked at KOMO-TV, I was well acquainted with Rod Chandler, and have always been grateful, the voters had a different idea, both in the Democratic primary and general election, about who should represent them in the U.S. Senate. Much later I worked for Commissioner Senn in Olympia and on her scrappy U.S. Senate Campaign. Quite a ride.

Excellent report.