When backpacking in the mountains, I’ve embraced the good-luck gesture of tapping wilderness and park boundary signs with my walking stick. More often than not, my destinations were places protected by a visionary moderate Republican Governor and later U.S. Senator named Dan Evans.

Evans’ boots have been on most of these trails, even after he had two knees rebuilt. This august public servant was known to skinny dip in mountain tarns.

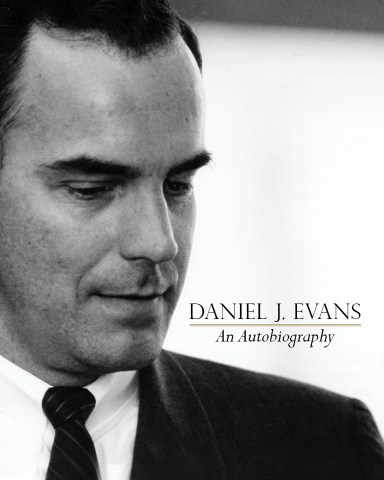

In his mid-90s, this pivotal figure in seven decades of Washington history – nicknamed “Straight Arrow” — has at last produced a coffee table book, Daniel J. Evans: An Autobiography, published under auspices of the Legacy Washington program of the Secretary of State’s office. (The book costs $35. To buy it, write to Legacy Washington at P.O. Box 40222, Olympia, Wash. 98504. Or go here online. There is also an excerpt from the book in a recent Seattle Times magazine.)

An amused description by Senate colleague Alan Simpson sums up Evans’ book: “Dan has an engineering mind. It’s precision and it’s putting link on link and girder on girder.” The autobiography is a litany of agendas starting with “A Blueprint for Progress,” on which the young legislator upset two-term Gov. Al Rosellini in 1964. The author’s relentlessly sensible speeches get quoted at length.

Dan Evans is not only a University of Washington graduate (and later UW regent), but very much a lucky Dawg. He was able to travel the high road while others did the messy work. Colleague Slade Gorton was the consigliere who put together the coalition of GOP and dissident Democrats, which took control of the state House of Representatives. A patrician patron, timber executive and art collector John Hauberg, donated money and put the arm on business bigwigs when the 1964 campaign was running on fumes.

The Seattle Times exposed Las Vegas gambling debts of Evans’ 1968 challenger, Attorney General John O’Connell, a Pierce County Democrat Seeking a comeback four years later, Rosellini destroyed himself in a debate by repeatedly referring to his dignified opponent as “Danny Boy.” A take-no-prisoners GOP state chairman, “Gummie” Johnson, beat back far-right Republicans – at least for a time.

“Dan is a wonderful man and if you don’t believe it, just ask him,” spouse Nancy Evans quipped as The Evergreen State College roasted its departing president. (Evans became Evergreen’s president after leaving the governor’s office and ascended to the U.S. Senate in a quick 1983 special election after Sen. Henry Jackson died of a ruptured aorta.)

The book is generous toward its author. Evans basked in favorable press coverage from the beginning to the end of his public life. Evans also sings praises of some prominent Democrats. He collaborated with gubernatorial challenger Martin Durkan to create the state Department of Ecology. He would beat Mike Lowry in the 1983 Senate race, but the two would later collaborate as co-chairs of the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Coalition to save playfields and heron rookeries around the state.

What “Straight Arrow” does not give us is a sense of the twists, turns, and backroom dealing that gets stuff done. One rare incident describes Evans fuming that reactionary Sen. Jessie Helms has held up Foreign Relations Committee action on confirming a top State Department appointment. Secretary of the Treasury James Baker hears out Evans’ frustration in the Senate dining room. Helms walks in. Baker quickly finds reason for the holdup. Helms wanted to install his nominee as U.S. Ambassador to Belize. On the spot messy work by Baker moved both nominations.

Evans spent much of his five-year tenure in the Senate being visibly frustrated. As governor, he could set the agenda and place girders on girders methodically. As a senator, he had to endure “bickering and protracted paralysis.” GOP colleagues eventually showed their frustration with him. Evans, not seeking reelection to the Senate, backed George H.W. Bush for President in 1988. He graciously offered his services as U.S. Interior Secretary in the Bush cabinet, citing years of work on public lands and Indian policy. Conservative Westerners vetoed the prospective appointment.

During my Seattle Post-Intelligencer years, our editorial page nominated Evans for vice president (twice), for Energy Secretary, for Interior Secretary and even for Education Secretary. Our top political columnist, Shelby Scates, was forever muttering to colleagues that “the word on the street” was that “Dan” was a shoo-in, particularly as President Ford’s 1976 running mate.

None of these ascensions happened. The Republican Party was moving right, while Evans stayed loyal to the moderate-liberal Rockefeller wing and went down with that leaky ship. Reagan forces denied Evans, a sitting GOP governor, a delegate slot to the 1976 national convention. The cadre of geeky-looking, reform-minded Republicans who fueled his 12 years in the statehouse moved on and out of public affairs. In the Senate, there was a personal jolt when Evans’ popular press secretary Sally Heet was stabbed to death, a crime which remains unsolved to this day.

The Senate made Evans get down and dirty, which livens up his autobiography. He threatened to put a hold on Reagan administration judicial nominations unless it renominated renowned Seattle trial lawyer Bill Dwyer to the federal bench. He then bested Strom Thurmond to win unanimous confirmation for Judge Dwyer. Creation of the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area was accomplished over opposition from the Reagan administration, the U.S. Forest Service, ex-Gov. Dixy Lee Ray, and two Oregon House members.

Deep into the book, one finds the first use of a cuss word by “Straight Arrow.” Evans’ environmental aide Joe Mentor is cobbling together the final text of the Columbia Gorge Act, “blank eyed” from incorporating suggestions from four Northwest senators. Take it away, Senator:

“Joe had finished drafting the bill late the night before, but when he hit the ‘print’ the text of the bill disappeared. We were working with a crotchety pre-Microsoft program called Prime. Joe had worked all night trying to retrieve the bill draft. Finally, in total frustration before I arrived, he typed in ‘Fuck you!’ The machine promptly disgorged the entire bill.”

The Columbia Gorge Act passed. In years since, the region’s declining lumber economy has been supplanted by outdoor recreation. Conservation has turned out to be a major “plus” in Washington’s economic growth. Hood River, Oregon, has become America’s wind surfing capital. Sen. John Kerry took a break from his 2004 presidential campaign to sample the winds.

Evans has grown ever more impatient with the Republican right. Put off by Donald Trump’s crude populism, he (and Slade Gorton) refused to vote for their party’s presidential nominee in 2016 and 2020. As a Theodore Roosevelt-style conservationist – his love of the outdoors was born as a Boy Scout at old Camp Parsons in the Olympic Peninsula – Evans is also suspicious of radical turns in the environmental movement: “The new breed of young urban environmentalists struck me as strident, immature, and less analytical. They have no institutional memory of what has gone on in the past.”

When I was a kid, and Evans was running his first statewide race, the state’s moderate Republicans were a welcome alternative to what KING-TV pundit Don McGaffin called “the sleaze wing of the Democratic Party.” When the Legislature adopted our state’s framework of environmental laws in 1970, Evans appealed for public support with a statewide TV broadcast. My Democratic state representative in Bellingham, Dick Kink, led the opposition.

Alas, reformers of a half-century back are getting a little long at the tooth, although the indomitable Evans still leads a hike into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area when Mainstream Republicans of Washington convene for their annual conference at Leavenworth. He remains the iconic figure in Northwest politics, a sensible reformer able to cobble together society’s compromises.

Now they are becoming an endangered species. The new book, long in the writer’s oven, reminds us of Evans’ model of achieving moderation in an era of polarization and demagoguery.(The book costs $35. To acquire it, write to Legacy Washington at P.O. Box 40222, Olympia, Wash. 98504. Or go to www.sos.wa.gov/legacy.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

“An Uncommon Republican”. ??

Actually he was quite representative of the Republican Party. There was nothing uncommon about Gov.Dan’s politics – he was just good at it.

Phil: I have always found that silence is golden when you have nothing to say.

Yes…….Something WE should all practice.

Thank you for this. I just ordered my copy.

I was finally able to meet Evans at a memorial service for my cousin’s wife a couple of years ago. I told him that as a Democrat, I always wanted to see him beaten, but in later years, I have really come to respect him.

I felt that it was a real honor to meet him.

Does Evans throw any light on why he signed the voters guide Statement For that monorail misadventure twenty years ago? It wasn’t clear then, and it’s less so now.

More details on how to purchase the new Dan Evans autobiography. To purchase a copy of the long-awaited Daniel J. Evans: An Autobiography, write to Legacy Washington at P.O. Box 40222, Olympia, Wash. 98504. Or visit our website at sos.wa.gov/legacy/stories/dan-evans or the online store. In the Olympia area, the book can be found in the Office of the Secretary of State at the Legislative Building. Stated cost is $40 plus $5 for mailing charges.

I always like Dan Evans.

I’m sorry he didn’t come out against Trump and the current Republican Party.

I understand that would be very difficult emotionally considering having been Republican for so many decades. But the country is more important than a party.