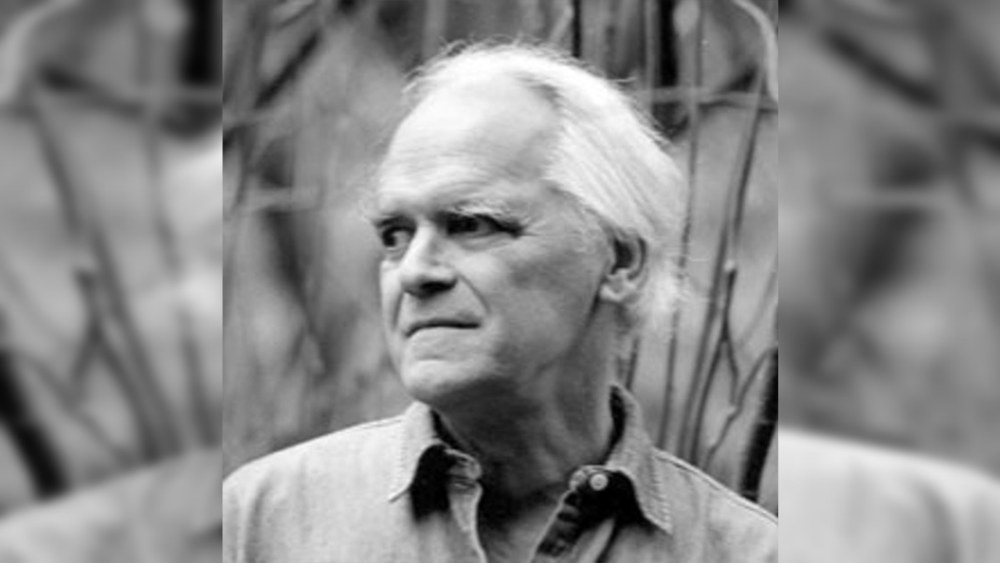

David Wagoner, “a giant of Northwest poetry,” died at age 95 on December 18, 2021. In addition to his renown as a poet, he was a novelist (one of whose novels was made into a movie by Francis Ford Coppola), a playwright, professor emeritus of the University of Washington, and the editor of Poetry Northwest for 36 years. He was a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and recipient of the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. David taught a master class at Hugo House from 2000-2019.

Reprinted with permission from Hugo House, where this tribute first appeared. Another fine tribute to the poet, and his influential role for many local poets, is this essay by Knute Berger in Crosscut.com.

When Hugo House invited me to write about David, the first recollection that sprang to mind was of a rainy February morning in 2010, shortly after I had relocated from New York City to Seattle, and was idly perusing the internet. My eyes fell on a flabbergasting piece of information: the great writer, David Wagoner, taught poetry workshops open to the general public—regardless of background or experience—for a modest fee, right here in my adopted city.

I glanced over my left shoulder and located (among hundreds of books I’d schlepped across the country) a copy of David’s Collected Poems and Straw For Fire, his compilation of fragments from Theodore Roethke’s notebooks. Although my undergraduate and graduate work had been in English literature, and I was an avid reader of contemporary poetry who had scribbled poems throughout her lifetime, I had never taken a creative writing class. Instead I’d become a dancer, choreographer, and actor, all of which I’d now put behind me.

How could I refuse this extraordinary opportunity to be in the presence of such a master as David Wagoner? My sense of good fortune was multiplied when I stepped inside The Richard Hugo House, in this earlier incarnation a homey gathering-place for writers of all stripes, at all levels. It would prove to be a kind of ad hoc grad school for me, as I gobbled up classes with scores of teachers, both local and visiting, while continuing to enroll, semester after semester, in David’s workshop.

In those days, David spent the first class teaching the hard facts of poetry writing—briefly stated. After that, he preferred to teach by using participants’ poems as examples. Since the workshops enjoyed many return students, David challenged himself to find novel ways to introduce the writing of poetry. But regardless of the approach he dreamed up, it was always peppered with quotes from Roethke, such as “Your assignment for the year is to read all the poetry written in the English language…there’s the library.”

Over the years, I collected plenty of quotes from David, himself. Here are a few of my favorites:

“Trust the subject more than yourself.”

“A poem has a beginning, middle, and end…but not necessarily in that order.”

“If I have a poem of 20 lines, and I count more than 10 adjectives, there is something wrong.”

“English is a series of vowels, interrupted by consonants.”

“Write too much—too many poems. There’s a better chance one will be good.”

David advised poets to take acting classes and study music. He said, “Control volume, pitch, register, tension, tempo, dynamics, and color as if you were a singer,” and he chuckled recalling his own theatrical performance as Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Another useful thing I learned from David was that the commonest flaws he observed in reading thousands of poems for Poetry Northwest were “underdoing the energy” and “quitting too soon.”

As time went by, David became a mentor and friend to me. When he could no longer drive himself from Edmonds to Hugo House, Kenneth Wagner and I chauffeured him and took him grocery shopping. When David’s mobility, hearing, and eyesight declined, he moved to a nursing home, and Kenneth became his advocate, driver, close friend, and teaching assistant. Occasionally, we took David to lunch, where Ken and I goaded him into telling stories of his adventures as a young poet, including recollections of time spent with such writers as Dylan Thomas. (It didn’t matter where we took him, he always ordered a hamburger!)

On my last visit with David, two weeks prior to his death, I read his own poems aloud to him, shouting through my mask. His response to many of them was, “I don’t recall writing that…it’s not bad.” When I was leaving, he said, “You’ve given me a great gift and I’m not going to be able to enjoy it very long.”

Speaking of last words, David often concluded his classes by saying, “Live merrily, and trust to good verses!”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

He was my creative professor in the mid- 1970s. Back then every student wrote a seagull poem because, well, who knows. I remember him coming into class one day, slamming down his pile of papers, and saying: “no more damn seagull poems.” He was simply one of the most disciplined writers I have ever known. He gave me the gift of “journaling” where he reminded students, the imagination can live on a daily basis.