A hymn honoring the Xhosa Christian prophet Ntsikana was heard along with music by Elgar and Bach at Seattle’s Epiphany parish this past Sunday night, as the Madrona Episcopal church celebrated the memory of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the world’s most famous Anglican.

South Africa is continents and oceans away from the Pacific Northwest, but this region’s faith community had close ties to Tutu, from days in the 1970s when he rose to fame protesting brutal crackdowns by the apartheid government. He came through Seattle no fewer than five times.

Those ties once provoked a stern rebuke from a Reagan cabinet secretary. Secretary of State George Schultz sat down with Hearst Bureau reporters during my tenure as the Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s Washington, D.C., correspondent. I evoked an apartheid event at St. Mark’s Cathedral, when D.C.’s Episcopal Bishop John Walker had been arrested protesting outside the South African embassy. What was Schultz’s reaction to cities and churches speaking out about international issues?

The buttoned-down Schultz quickly came unbuttoned, upbraiding cities and “groups” that were taking foreign policy into their own hands. The Reagan Administration was working backstage with Pretoria on a policy of “constructive engagement,” he told us, seeking to get the whites-only government to ease its oppression. Protests in both Washingtons would only encourage sentiments for Afrikaners “to go to the lager.”

The opposite turned out to be true. Such renowned South Africans as Cry the Beloved Country author Alan Paton, on a Seattle visit, had gloomily predicted that sustained violence was inevitable were the country to change. By contrast, Tutu preached peaceful liberation and predicted it would happen. Eventually, South Africa’s white leaders concluded their system was politically and economically untenable.

“Now I can go back to being a bishop,” Tutu delightedly exclaimed when Nelson Mandela assumed the presidency. Not so fast. Tutu was called upon to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which aired testimony by the former oppressors of struggles only recently ended. In bringing the country together again, the process applied the principle of forgiveness through confession.

Words of the archbishop, read Sunday night at Epiphany Church, spoke to his country’s struggle and today’s world: “True reconciliation is based on forgiveness, and forgiveness is based on true confession, and confession is based on penitence, on contrition, on sorrow for what you have done . . .

“We have had a jurisprudence . . . in Africa that was not retributive but restorative. When people quarelled, the main intention was not to punish the miscreant but to restore good relations. For Africa is concerned, or has traditionally been concerned, about the wholeness of relationship. That is something we need in our world, a world that is polarized, a world that is fragmented, a world that destroys people.”

“Restoration heals,” Tutu preached, a message which saw him awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984, at a time when he was general secretary of the South African Council of Churches. He would later serve as Archbishop of Cape Town and Anglican primate of Southern Africa. In retirement, Tutu carried his message to the world, and quite often to this corner of North America. Audiences learned of South Africa’s liberation struggles in language honed at King’s College, London, when Tutu was a young priest. “I am not interested in picking up the crumbs of compassion thrown from the table of someone who considers himself my master: I want the full menu of rights,” he said in accepting an honorary degree in 2000 from Seattle University.

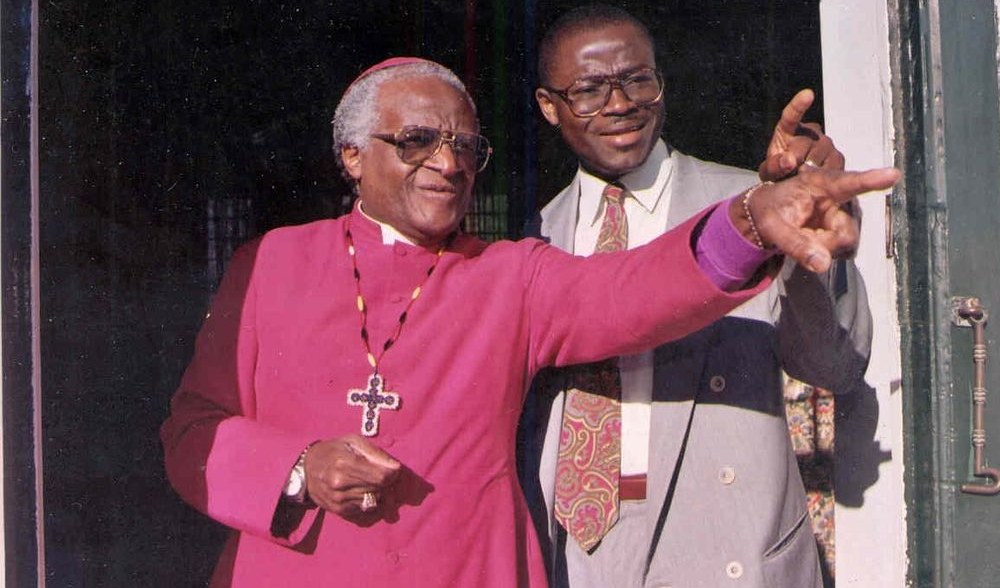

He was back in town in 2002 to accept an honorary degree from the University of Washington, the first such degree awarded by the UW since 1921. He helped St. Mark’s Cathedral celebrate its 75th anniversary in 2006, raising money for the Desmond Tutu Peace Foundation and preaching at evensong. (A Tutu protégé, Robert Taylor, was dean at the cathedral.) Before finally returning to his side of The Pond, the Archbishop would appear with the Dalai Lama in Seattle – the two coauthored a book – and speak to 15,000 people at the Tacoma Dome in the company of Bill Gates Sr. and Seahawks Coach Pete Carroll.

It was beneficial to have Tutu around. In an era when the religious right sought to monopolize — and twist — the message of faith, the archbishop was a voice for progressive, inclusive Christianity. The readings at Epiphany on Sunday were carefully chosen by Dr. Judy Mayotte, a close friend of Tutu and officer with the Peace Foundation. A salient passage was read by the congregation:

“Our God is a God who has a bias for the weak, and we who worship this God, who have to reflect the character of this God, have no option but to have a like special concern for those who are pushed to the edges of society, for those who because they are different seem to be without a voice. We must speak up on their behalf, on behalf of the drug addicts and the down-and-outs, on behalf of the poor, the hungry, the marginalized ones, . . . on behalf of those who have different sexual orientations from our own. We must be where Jesus would be, this one who was vilified for being the friend of sinners.”

With the reading of such words, no sermon was needed, although Epiphany’s rector Rev. Doyt Conn, Jr., delivered a delightful and personal welcome. It turned out that Tutu was graduation speaker at Conn’s seminary graduation. On that same day, Conn found he was to become a father. He and his wife agreed that, if a boy, the child would be named Desmond.

A few weeks later, in the mail, came a book by Tutu, inscribed by the archbishop to the not-yet-born baby. “To this day,” said Conn, “it remains a mystery to me how, who, arranged for this to happen.” A few moments later, a tall young man named Desmond Conn took to the pulpit and read from Tutu’s “God Has a Dream”:

“The principle of transfiguration says nothing, no one and no situation, is ‘untransfigurable,’ that the whole of creation . . . waits expectantly for its transfiguration, when it will be released from its bondage and share in the glorious liberty of the children of God, when it will not be just dry inert matter but will be translucent with divine glory.”

A hopeful, holy man, Archbishop Tutu passed away at 90 on Boxing Day.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An additional memorable reading at this Liturgy from the writing of Archbishop emeritus Tutu was delivered by one of Seattle’s dedicated and most admired historians of our city, its African-American community and heritage, Mary Henry, a member of the Epiphany congregation : “How do we embrace our enemies? How do we get rid of the hatchet forever instead of just burying it for a time and then digging it up later?’ True, enduring peace– between countries, within a country, within a community, within a family – requires real reconciliation between former enemies and even between ones who have struggled with one another.”