About the time I joined Boeing, Milton Friedman published his famous article in The New York Times Magazine. The influential essay argued that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” Not also helping society or customers or employees – just shareholders. This proved prophetic, for Boeing and American corporations.

At the time, I was a newly liberated Air Force lieutenant and freshly minted accountant. I became part of a group of baby boomers hired following the 1969 “Boeing Bust” to manage the process of moving Boeing’s accounting from paper to computers. I was the only one without an MBA, and I had gone from being a skeptic of Boeing — the Lazy B where many of my friends’ boring dads worked — to an admirer after my time as an Air Force officer. I soon bought the belief that commercial aviation’s potential to bring people together could change the world for the better.

Two of the interesting things I learned from my new colleagues were how many shared the belief in the transformative power of commercial aviation and space. The other lesson was how many of my MBA contemporaries found Boeing stultifying, keeping them from becoming the CEOs they trained to be. While I subscribed to the first belief, my stint in the Air Force prepared me to accept that I wasn’t going to make CEO-level decisions anytime soon.

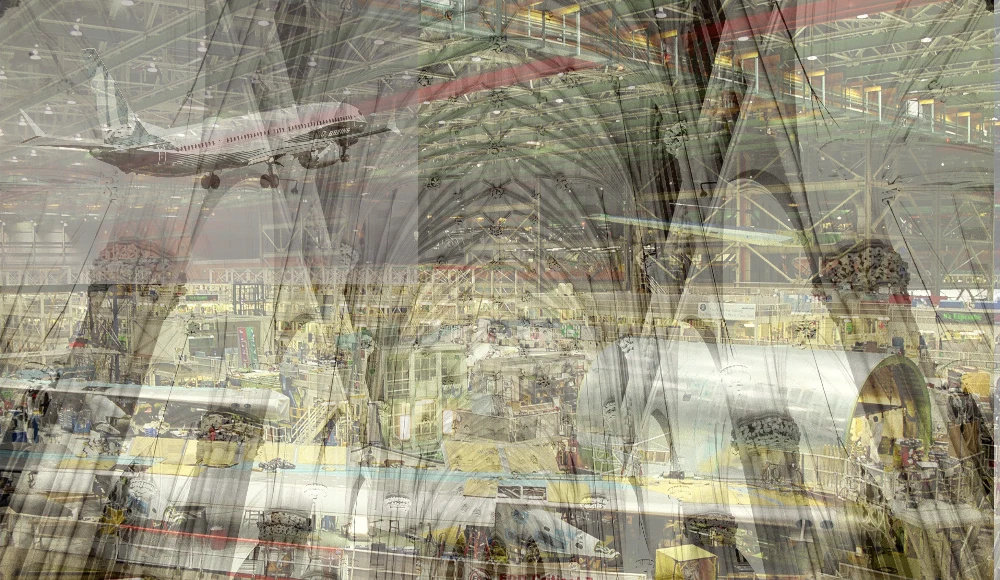

I also learned that commercial airplanes are very complicated things. One of my mentors told me commercial airplanes were “the cathedrals of the 20th century.” For many, aviation is a religion, but what my mentor meant was that airplanes, as with cathedrals in the Middle Ages, represented the pinnacle of technical achievement in the technology, complexity, and investment of capital and people, and the extended time and continued commitment they required.

Central to Boeing’s success was a very disciplined approach to designing and building airplanes, plus an amazing culture that balanced risk and caution. Airplanes require very detailed specifications, and those specifications must be complexly integrated. As Peter Robison recounts in his new book on Boeing, Flying Blind, this process was based on precise standardization and excellence managed by “Functional Fathers” with experience, expertise, and relationships across the company.

The mantra I grew with as a Boeing employee was “Quality, Schedule, then Cost. Quality because it’s a really bad day when an airplane falls out of the sky. Schedule because airplanes are very expensive, and customers count on getting them into revenue service as soon as they’re delivered – and they’ve built their flight plans around that date. Cost, because we do want to sell another airplane. The hierarchy of values spoke to an important organizational culture.

Robison tells a story illustrating this. The famous test pilot Tex Johnston, he of barrel-rolling the Dash 80 over Seafair (twice), informed the legendary senior designer Ed Wells during the 707’s testing that the tail needed to be redesigned. Wells’ reply, “We will fix it,” bespoke the commitment to quality before schedule or cost.

I wish Robison would have also told the story of another famous designer Jack Steiner and the 727, one more saga inculcated in new employees. After the success of the 707 in the ‘50s, Steiner argued for a smaller, three-engine aircraft to serve regional markets. Boeing’s board knew how the 707 stretched the company finances and remained averse to further financial risk. So, Steiner tapped the rich research-and-development budget the board provided to complete the preliminary design for the 727.

A preliminary design establishes the performance of a proposed airplane, but not the details necessary to build the plane. As the story went, Steiner brought the board a commitment from United Airlines to be the lead customer based on the preliminary design, and the board approved, probably with much grumbling. The lesson? Better to seek forgiveness than permission – if you’re doing the right thing. And “the right thing” was fidelity to the values and vision of Boeing.

Robison tells the story of that early vision and values well – of Bill Allen, T Wilson, Ed Wells, Joe Sutter, Alan Mullally, Stan Schorscher, and many others. The first third of the book sits with John Newhouse’s The Sporty Game in definitively telling the saga of commercial aviation.

And then the “hunter killer assassins” arrived — after, in Boeing CEO T Wilson’s words, “buying us with our money.” Many believed McDonnell Douglas, which Boeing bought in 1997, built its business on a less ethical set of values than Boeing. One line was that Boeing designed, built, and delivered airplanes — and then spent the rest of the airplane program’s life doing lightening exercises. By contrast, Douglas designed, built, and delivered their airplanes — and then spent the remainder of the program’s life in strengthening exercises. Many felt that Boeing lost government contracts where Boeing had the technical solution and McDonnell had the political one.

So, when Defense Department contract acquisition official Darleen Druyun and McDonnell Douglas Vice President Mike Sears went to jail as “Boeing Employees” after Druyun admitted to “systematically favoring Boeing on acquisition deals” and those favors were directed to McDonnell Douglas before the merger, that decision cut those of us “heritage Boeing employees” to the quick.

The strongest part of Robison’s book and my least favorite is the next two thirds covering the destruction of Boeing’s culture and the tragedies of the 787 and 737 MAX, planes that demonstrated the New Boeing’s narrow responsibility to increase profits. If airplanes are complex, so are human relationships. The 787 program outsourced chunks of the 787 to “partners,” thereby rupturing much of the web of relationships central to the culture of safety. As Robison points out, the partners, not Boeing, now owned the designs, and that meant reducing information-sharing and design-integration.

The 787 outsourcing to South Carolina was one consequence of these decisions. Boeing had to buy Vought’s Charleston facility when they didn’t have the engineering capacity or manufacturing capabilities required for the 787 fuselage. This entailed outsourcing from Everett’s unionized work force to Charleston’s inexperienced, non-union one. I have friends, formerly senior Boeing manufacturing folks, who refuse to fly on South Carolina 787s.

Then after the losses on the 787, Airbus launched the A320 Neo, forcing Boeing’s hand on the next-generation 737. To save money Boeing could dig deep and make a 737 re-do, or just bring the airframe up to current technological standards. Profit won out. Cost now came first, then schedule, and finally quality. The wisdom of the MBAs and Milton Freidman’s dictum, as Robison points out, ended up costing more, taking longer, and jeopardizing the quality Boeing was once famous for. It may have killed the company. The details Robson covers should astonish readers in Jet City. One fact that I found paticularly astonishing was Robison’s revelation that Boeing currently invests half what Airbus does on R&D. Jack Steiner, I am sure, is spinning like a top in his grave.

One of my favorite parts of Robison’s book was a paragraph some 70 pages into the book, closing the story of the move of executive offices to Chicago. One of the corporate “leaders” brought in by McDonnell Douglas was Debbie Hopkins, who had replaced Boyd Givan as Boeing’s CFO, in large part over a disagreement over financing airplane sales. Stonecipher wanted to emulate GE Capital, Jack Welch’s financing arm, and Givan opposed it. Givan argues that the risk associated with designing and building airplanes was enough, without taking on the risk of airline operations as well. Givan was arabesqued into retirement, and Hopkins brought in “modern” financial and business management to Boeing.

Later, as Boeing HQ moved to Chicago, Hopkins moved to Lucent Technologies, because the growth was in high tech, not old manufacturing. During her stint at Lucent accounting errors and the burst dot-com bubble caused Lucent shares to crater. Eventually, Boeing wrote off serious losses from Boeing Capital. Score one for our Functional Fathers’ wisdom, I thought.

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

MBA degrees should require 5 yrs. of work credit before acceptance into the program.

One of the civic harms of the decline of Boeing is the loss of a pace-setter in local politics and institutions. When it came to a big local cause, such as United Way or building a new symphony hall, Boeing took its time to decide but when it did all the lesser donors would know how to fall in line, with Boeing setting the top rung. Boeing also would underwrite salaries when its executives signed up for a nonprofit board or to run for office. There was, for instance, a chair reserved for Boeing on the Seattle School Board. That’s all gone, now, and many good causes suffer from this lack. The leadership deficit is echoed in the outside ownership of local banks as well as Safeco and Burlington Northern. Boeing’s charitable donations are now controlled by Chicago and as Boeing has spread throughout the country there are many more mouths to feed (and less food to dispense).

The top corporate donors to the 147 Republican members of Congress (139 members of the House and eight senators) who voted to overturn the election results in Pennsylvania, Arizona, or both states. and their party committees were Boeing ($346,500), Koch Industries ($308,000), and American Crystal Sugar ($285,000).

While Milton Friedman sits at the top of Capitalist thinkers and commentators. he never advocated short term profits as you suggest. Profit is the goal but to achieve same one cannot ignore values such as safety and integrity.,

Stake holders are just that and very much a part of profitability writ large.

Friedman is too often painted as a villain – even taught as such to a whole generation. the basis of capitalism is a belief that markets, not government are the most efficient allocator of resources. Yes, there are winners and losers (risks and rewards). Capitalism isn’t perfect, but no better way has yet to prove itself for number of people.

to clarify, Boeing’s troubles belong to Boeing– Not to Dr. Friedman