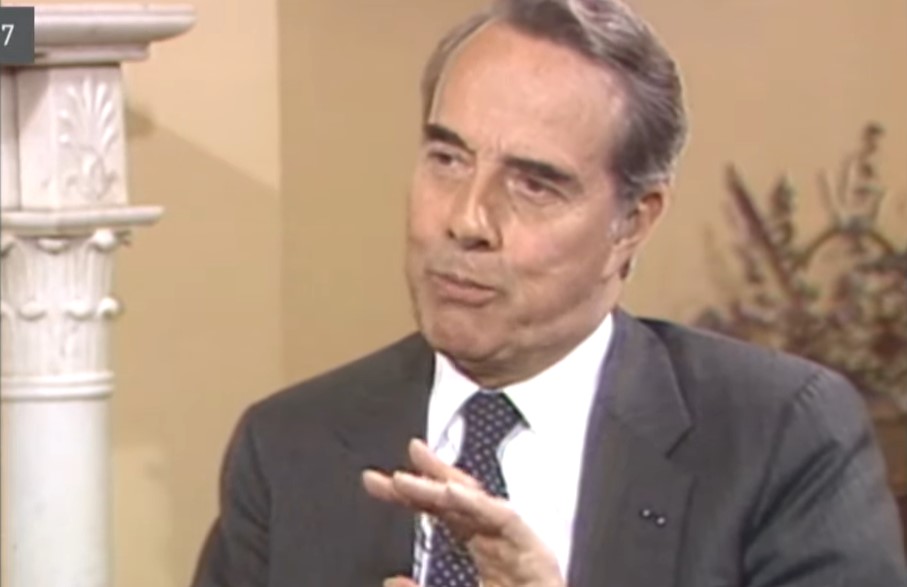

Bob Dole came to Seattle in 1992, boosting the U.S. Senate campaign of GOP Rep. Rod Chandler and hoping to hold back the “Year of the Woman” tide that was about to sweep former Shoreline preschool teacher Patty Murray into the world’s greatest deliberative body. The press conference was wrapping up when I thought to ask the 1996 Republican presidential nominee, and longtime Kansas senator, a final question. What did he think of the glowering Dole parody by comedian Dan Aykroyd on Saturday Night Live?

“Ha, ha, ha, I’ve wondered about that myself,” Chandler interjected. Dole gave a chuckle, said the staff had taped it for him to see, and ended the presser. I packed up my papers to leave but felt a vise-like grip on my shoulder. With his good left arm, Dole spun me around, gave me a mock hard look, and said: “I know who you are.”

The Dole wit. The sometime Republican hatchet man could be wickedly funny. When ex-Presidents Carter, Ford, and Nixon decamped to Cairo for the funeral of slain Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Dole remarked: “There they go, See no evil, Hear no evil, and Evil.” He had served as Republican National Chairman when Nixon was fighting impeachment.

A complicated guy, the politician who died at 98 in his sleep overnight Sunday, Dole ran for president in 1980, 1988, and 1996, and was Republican vice presidential nominee under Gerald Ford in 1976. The ’76 campaign introduced a dour Dole to the American people, with his debate references to young Americans who had died in “four Democrat wars.”

Dole “has richly earned his reputation as a hatchet man,” opponent Walter Mondale retorted. Dole later acknowledged: “I was told to go for the jugular and I did – mine.” Wife Elizabeth later took him through a tape of the debate, as a lesson in how not to darken your image.

He grew up in Depression-era Kansas, hustled as a kid, and dreamed of becoming a surgeon. World War II made him a political operator. A member of the legendary 10th Mountain Division, he was hideously wounded on April 14, 1945, in one of the war’s last engagements. Dole lost a kidney and went through life with a disabled-in-place right arm.

He started as a county attorney, won election to Congress in 1960 (the year John F. Kennedy was elected president) and would serve in the Senate for 27 years. He spent a decade as Senate Republican Leader. Congress was his life. Returning to his digs in the Watergate, Dole would watch C-SPAN. He recreated by sunning himself on a deck outside his office, and at a condominium in Florida.

Dole could be cruel and cutting. Abruptly and without warning, he would tell his first wife of 23 years, Phyllis, a nurse who had helped his recovery, that he wanted a divorce. I witnessed this streak in the 1988 campaign, interviewing Dole en route to a GOP candidates forum at a rickety minor league baseball park in Indianola, Iowa. We drove up behind the baseball field, seeing only a couple of people. Dole lit into his youthful advance kid for wasting his time by scheduling this “useless” event. The kid’s neck turned red. But we rounded the corner to see the stands filled with Republicans. Dole flipped moods in an instant, being the lone candidate to make his way up into the stands to spend time with the folks.

He nursed resentments against the privileged upbringing of rival George H.W. Bush, a man in the memorable words of Texas Gov. Ann Richards “who was born on third base and thought he hit a triple.” We media folk looked on from an NBC studio, when Bush upset Dole in the New Hampshire primary, as the two men appeared on screen together. Is there anything you want to say to Vice President Bush, asked the news anchor? “Stop lying about my record!” Dole snapped.

But there was another side of Dole: He was one of the Senate’s old bulls. They were a club, even as rivals and ideological opposites. Dole embraced compromise as a virtue. He may have called President Carter a “Southern-fried McGovern,” but worked with colleague George McGovern on landmark legislation to establish the food stamps and school lunch programs. He teamed with Democratic colleagues to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act, saying as it became law: “And I am forever grateful. I know Sen. (Edward) Kennedy and Sen. (Tom) Harkin are. Have you ever seen so many wheelchairs at a White House signing ceremony?”

He and Democratic Sen. Daniel “Pat” Moynihan in 1983 rescued a deadlocked bipartisan Social Security commission. Dole teamed with “Greatest Generation” senators on both sides of the aisle to establish the World War II memorial in the nation’s capital.

The politics of confrontation were coming on as Dole prepared to run for President in 1996. The new House Speaker was Newt Gingrich, who had called Dole “the tax collector for the welfare state.” Gingrich forced a government shutdown later that year which damaged Republicans’ prospects of beating Bill Clinton.

Dole announced on June 11, 1996, that he would quit the Senate to campaign full-time for President. He was back on the Senate floor the next morning announcing the day’s agenda. He came across as dated figure, promising to build “a bridge to a time of tranquility, faith, and confidence in the nation.” Clinton promptly countered with his “bridge to the 21st Century.”

After a University of San Diego debate, Dole left the stage while Clinton lingered on to talk with citizen members of the audience. By protocol, the President’s motorcade must leave a scene first. Dole fumed in his holding room while Clinton met the folks. Clinton found ways to get under Dole’s skin. The administration launched a major campaign highlighting the dangers of smoking to health. One of the first things Dole had learned to do, recovering from his war injuries, was to light his Luckies. Clinton and VP Al Gore celebrated Earth Day doing muscular outdoor work with a cleanup crew at Great Falls Park on the Potomac River. Dole was unable to cut a Philly cheese steak sandwich served during a campaign appearance.

Three days before being sworn in for his second term, Clinton awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to the man he defeated. The Dole wit was memorably displayed as he rose to say, “I, Robert J. Dole, to solemnly swear . . .” As the East Room erupted in laughter, he added: “Sorry, wrong speech. But I had a dream that I would be here this week, receiving something from the President, but I thought it would be the front door key.”

In retirement, Dole became a public character. He did a cameo on Saturday Night Live, popularized the term “erectile dysfunction” in a TV spot for Viagra, and hawked Pepsi in another ad. (David Letterman showed a picture of Godzilla with the label “Bob Dole on Viagra.”) He boosted the career of second wife Elizabeth, who served a term in the Senate from North Carolina and ran a brief, stillborn campaign for President.

The last years saw brief reappearance of the bad Dole, but also a touching tribute to another old soldier. Dole became the only former Republican presidential nominee to back Donald Trump for President in 2016. A politician who cherished a reputation for giving his word was endorsing a man whose word was (and is) worthless.

When once-bitter foe George H.W. Bush lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, the 95-year-old Dole was helped up from his wheelchair to his feet, and saluted the 42nd President, a fellow World War II combat veteran. “I didn’t go there with the intent to salute, but I did,” he said later.

The last political figure of an American era has passed.

This story is reprinted from Northwest Progressive Institute’s “Cascadia Advocate.”

Discover more from Post Alley

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.